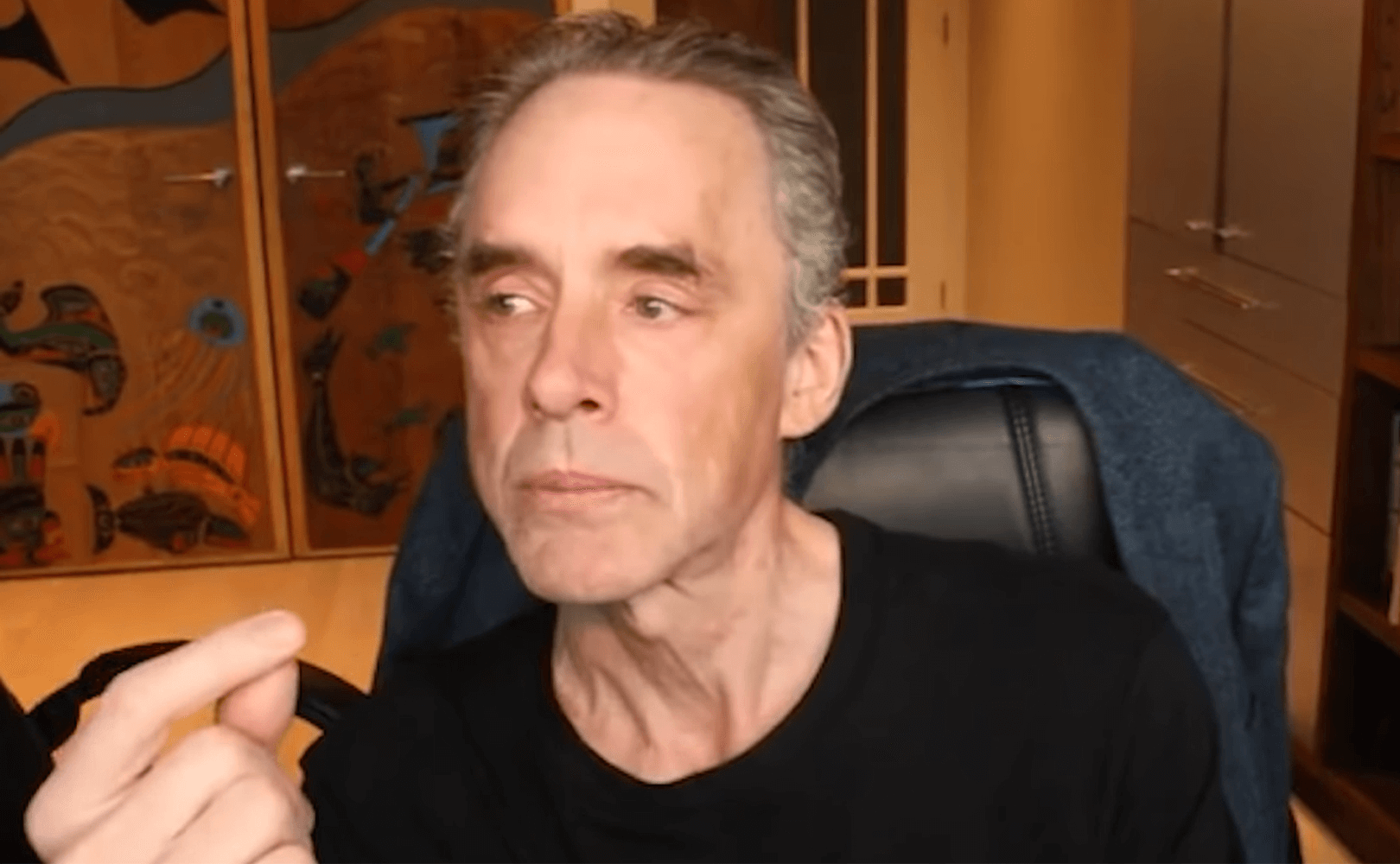

Jordan Peterson is one of the most fascinating thinkers in the world today. He has captured the attention of untold millions with his attempt to find meaning and truth in a time when people seem hell-bent against the apprehension of either.

And over the past two years, he’s gone through hell and back.

In order to tell the story I want to tell you, I need to offer some backstory on what he’s been dealing with, because it won’t make nearly as much sense without it.

So here he is in his own words on what happened. The following is taken from the prologue of his most recent book, Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life:

On the fifth of February 2020, I awoke in an intensive care ward in, of all places, Moscow. I had six-inch tethers attaching me to the sides of the bed because, in my unconscious state, I had been agitated enough to try to remove the catheters from my arm and leave the ICU. I was confused and frustrated not knowing where I was, surrounded by people speaking a foreign language, and in the absence of my daughter, Mikhaila, and her husband, Andrey, who were restricted to short visiting hours and did not have permission to be there with me at my moment of wakening. I was angry, too, about being there, and lunged at my daughter when she did visit several hours later. I felt betrayed, although that was the furthest from the truth. People had been attending to my various needs with great diligence, and in the wake of the tremendous logistic challenges that come about from seeking medical care in a truly foreign country. I do not have any memory of anything that happened to me during the most recent weeks preceding that, and very little between that moment and my having entered a hospital in Toronto, in mid-December.

In January of 2019, Peterson’s daughter, Mikhaila, had to replace most of her artificial ankle, after struggling for years with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis which led to the replacement of both ankle and hip.

In March of that year, Peterson’s wife, Tammy, had to undergo what was believed to be routine surgery for a treatable kind of kidney cancer, only to discover that she was “suffering from an extremely rare malignancy, which had a one-year fatality rate of close to 100-percent.” Miraculously, surgeons were able to bring this aggressive cancer to a stop, but she had severe complications, and according to Peterson, she was “near death daily for months.”

And as Peterson was attending to his wife’s and daughter’s health, he suffered his own catastrophe.

“I had begun to take an antianxiety agent at the beginning of 2017,” he writes, “after suffering from what appeared to be an autoimmune reaction to something I had consumed…” He suffered extreme symptoms, from continuous anxiety to feeling freezing cold to extremely low blood pressure and insomnia.

He was prescribed a benzodiazepine by his family physician, and it helped tremendously. During this same time, his star was rapidly rising, and his stress levels along with it. Although the medication helped — and although it was one he believed to be not just effective but safe — something changed in March of 2019.

His anxiety spiked along with the health problems endured by his wife and daughter. When he tried to get off the medication, the withdrawal symptoms were, he writes, “truly intolerable — anxiety far beyond what I had ever experienced, an uncontrollable restlessness and need to move (formally known as akathisia), overwhelming thoughts of self-destruction, and the complete absence of any happiness whatsoever.”

After trying unsuccessfully to return to his dosage and taper off, he eventually wound up in the hospital in Toronto in December of 2019, and it was, he says, “at that point that my awareness of events prior to my awakening in Moscow ends.”

His family moved him to Moscow in 2020, where he was placed in a medically-induced coma for 9 days to allow him to endure the effects of withdrawal while unconscious — an aggressive treatment not available in most of the world. He spent much of January in the ICU, with little memory of any of it. When he did become cognizant, he was placed in a rehab facility, where, he relates:

I had to relearn how to walk and up and down stairs, button my clothes, lie down in bed on my own, place my hands in the proper position on a computer keyboard, and type. I did not seem to be able to see properly—or, more accurately, see how to use my limbs to interact with what I perceived. A few weeks later, after the problems in perception and coordination had essentially abated, Mikhaila, Andrey, their child, and I relocated to Florida for what we hoped would be some peaceful time of recuperation in the sun (very much welcome after the cold grayness of midwinter Moscow). This was immediately before worldwide concern erupted over the COVID-19 pandemic.

His recovery since has been slow and uncertain, with many setbacks. To watch Peterson on his world tour, such as when he gave this fascinating conference in Brisbane, Australia, in February of 2019, was, as my friend Kale Zelden put it, to see “a man in full.” To watch him now, however, is to observe a man diminished.

I do not say this as a critique.

Post-Coma Peterson is clearly suffering. I am uncertain if his pain is predominately mental, emotional, or physical — or if it’s a combination of the three — but he is certainly hurting. As he wrote in the prologue to his book:

I am not going to make a claim that the events that befell my wife, me, and those who were closely involved in her care added up, in the final analysis, to some greater good. What happened to her was truly awful. She experienced a severe and near-fatal crisis of health every two or three days for more than half a year, and then had to cope with my illness and absence. I was plagued, for my part, with the likely loss of someone whom I had befriended for fifty years and been married to for thirty; the observation of the terrible consequences of that on her other family members, including our children; and the dire and dreadful consequences of a substance dependence I had unwittingly stumbled into. I am not going to cheapen any of that by claiming that we became better people for living through it.

However, I can say that passing so near to death motivated my wife to attend to some issues regarding her own spiritual and creative development more immediately and assiduously than she might otherwise have, and me to write or to preserve while editing only those words in this book that retained their significance even under conditions characterized by extreme suffering.

In a discussion this year with fellow Intellectual Dark Web luminary Brett Weinstein, Peterson admitted to his diminished capacity. He said that he’s only “working about two hours every three days now” after years of working long, fruitful hours. And further:

I get up, I can hardly stand up when I wake up in the morning. I feel so bad I can’t believe I can be alive and feel that bad. I stumble downstairs and I’m in the sauna for about an hour and a half and then I can stand up long enough to have a shower, which I do for about 20 minutes, and I scrub myself from top to bottom trying to wake up. And then, I can more or less get upstairs. And I eat and then I go for…I walk like ten miles every day because I need to do that in order to deal with this… whatever it is is that’s plaguing me. And I can get myself to the point where by this time in the afternoon I’m more or less functional, but then it repeats the next day.

For a man who simulteanously taught at university, had a clinical practice, wrote books, and produced such a noteworthy stream of thought that he suddenly caught the attention of the world, I can only imagine how debilitating this must feel.

And all of this sets the stage for the interview I want to talk about. In it, Peterson talks with Jonathan Pageau, an artist who makes “Eastern Orthodox Icons and other traditional Christian images in wood and stone.”

It is important to note, here, that Peterson is not overtly religious, and has not, to my knowledge, professed a specific creed. But he gives great credit to Christianity, and Catholicism in particular. It comes up a great deal in his work. He once notably said that Catholicism is “as sane as people can get.”

In his discussion with Pageau, which was published in March, 2021, he confronts the serious claims of Christianity in a moving moment. I’ve linked the timestamp, but if you have trouble, it begins at 21:42 and continues straight through to 24:08, at least (though the discussion continues past that point):

For those who are unable for some reason to watch the video, here’s a snippet I’ve transcribed:

But the difference, and C.S. Lewis pointed this out as well, the difference between those mythological gods and Christ was that there’s a, there’s a representation of, there’s a historical representation of his existence as well. Now you can debate whether that’s genuine. You can debate about whether or not he actually lived and whether there’s credible objective evidence for that, but it doesn’t matter in some sense, because, well it does, there’s a sense in which it doesn’t matter because there’s still a historical story so what you have in the figure of Christ is an actual person who actually lived plus a myth and in some sense Christ is the union of those two things. The problem is that I probably believe that. But I don’t know…I’m amazed at my own belief and I don’t understand it.

At this point, Peterson becomes visibly and audibly choked up, as Pageau laughs empathetically — even somewhat joyfully — at what he is struggling with. Peterson continues, his voice cracking:

Because…I’ve seen…sometimes, the objective world and the narrative world touch. You know that’s Jungian synchronicity. And I’ve seen that many times in my own life. And so in some sense I believe it’s undeniable, you know, we have a narrative sense of the world. For me that’s been the world of morality. That’s the world that tells us how to act. It’s real. Like, we treat it like it’s real. It’s not the objective world. But the narrative and the objective world touch. And the ultimate example of that in principle is supposed to be Christ. But I don’t know what to…that seems to me oddly plausible. But I still don’t know what to make of it. It’s too…partly because it’s too terrifying a reality to fully believe. I don’t even know what would happen to you if you fully believed it.

“If you believed in the story of Christ?” Pageau asks. “Or if you believed in…history and let’s say the narrative meet?”

“Both, I think.” Peterson responds. “I think you…because when you believe that you buy both those stories. You believe that the narrative and the objective can actually touch.”

It’s a moving moment.

Later on in the discussion, beginning at about 34:20, Peterson explains his views further:

People have asked me whether or not I believe in God, and I’ve answered in various ways. “No, but I’m afraid he probably exists.” That’s one answer. No, but I’m terrified he might exist. That would be a truthful answer to some degree. Or that “I act as if God exists,” which I think is, I do my best to do that, but then, there’s a real stumbling block there because…. there’s no limit to what would happen if you acted like God existed. You know what I mean? Because I believe that acting that out fully…I mean, maybe it’s not reasonable to say to believers, “You aren’t sufficiently transformed for me to believe that you believe in God. Or that you believe the story that you’re telling me. You’re not a sufficient…the way you live isn’t a sufficient testament to the Truth.”

And people would certainly say that, let’s say, about the Catholic Church, or at least the way it’s been portrayed is that, with all the sexual corruption for example it’s like, “Really? Really? You believe that the Son of God…that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and yet you act that way and I’m supposed to buy your belief?!” And it seems to me that the Church is actually quite guilty on that account because the attempts to clean up the mess have been rather half-hearted in my estimation, and so I don’t think that people…Christians don’t manifest this, and I’m including myself I suppose in that description, perhaps, um, don’t manifest the transformation of attitude that would enable, that enables the outside observer to easily conclude that they believe.”

His last point is hard to argue with, but it at this point, Pageau interjects with something helpful:

The way to deal with that, or the way to understand that, is that it…they do, but they do in a hierarchy. There’s a hierarchy of manifestation of the transformation that God offers the world, and we kinda live in that hierarchy. And those above us hold us together, you would say.

And so in the Church there’s the testimony of the saints. There’s, there are stories. There are hundreds and hundreds of stories of people who lived that out in their particular contexts to the limit of what is possible to live it. And even today there are, there are saints, living saints, who, for example, like in the Orthodox tradition we have this idea of what they call “the gift of tears,” or the joyful sorrow, of people who live in prayer with weeping, constant weeping. And it’s this kind of strange mix of joy and sadness, which they, which kind of overwhelm them and they live in that joy and sadness non-stop, and they, you know, without end. So that exists, but then we in this…that’s one of the reasons why, that’s kind of one of the reasons why when I talk about this idea of intention, like it manifests itself in the Church as well, it’s that, you often say, and I understand it, when you say something like, you know, “I act as if God exists,” or, you know, “I’m afraid to say that God exists,” and I think it’s because you think, or you tend to think, that the moral weight like of that is so strong that you would, you would crumble under it. That you’d just be crushed under it.

Peterson responds, “I believe that!”

When I listened to this, I was reminded immediately of another Orthodox thinker, Fr. Seraphim Aldea of Mull Monastery, whose videos I have shared with you in the past. Over the past year, as I’ve struggled with my own faith, I have found great consolation in the words of this priest. In one of his videos back in January of this year, he addressed the same point Pageau makes about the hierarchy of the manifestation of transformation in God via the saints.

He begins this discussion at about 7:30 in this video. My transcript follows:

Slowly, almost imperceivably to us, we move into another realm where we are surrounded by other human beings. The ones who are now Saints in the kingdom of heaven. And instead of dealing with the fallenness of our brothers and sisters here, and our own fallenness here, we are dealing with the sanctity the holiness of our brothers and sisters in heaven and our fallenness compared to them.

That’s why as we grow closer to God, as we grow closer in this communion with the Saints, instead of feeling better about ourselves we end up feeling worse about ourselves because we are surrounded by Saints. We are no longer surrounded exclusively by the examples of our fallen brothers and sisters in this world. Compared to them, we are just as good, or just as bad. Sometimes we are actually better than they are, and that feeds our pride. But when we slowly graduate from this fallen class, and we are entering humbly and quietly in all the class of the saints, the kingdom of the Saints, compared to them we shall never be better and we shall never even be equal. We are always going to be lower than them. And this of course feeds our humility, our humbleness, and this of course kills our pride, because there’s nothing to feed our pride anymore.

And all of a sudden, from being maybe one of the best students in the fallen classroom of this world, we end up being the worst students in the amazing classroom of the Saints. But it is better to be the last in the kingdom of God than to be the first among the fallen ones. I have a feeling if you read the Gospel with this lens in your heart and in your mind, you will see that the fathers who are teaching us to look at ourselves through this lens were perfectly right. Saint Sophrony of Essex tells us not to let go of the perfection of the Saints, not to stop looking at their examples, but to look at them as if they are stars somewhere up in the skies, and we know, we are fully and painfully aware that we cannot reach out and grab it and make that star our own. But by looking at that star, we make certain that we move in the right direction. That we do not lose our life. We do not waste the time of our life by moving to the right side, to the left side, up and down and everywhere around until we get into our 50s and 60s and 70s and and even later and we realize, “Oh I’ve just wasted my life following nothing but my pride.” Instead we have this example, this perfect star of the life of the saints, and even if it’s painful because we know we cannot reach out and grab it, even if it’s painful and humbling, at least by looking straight at their example and being surrounded by the community of the Saints — slowly, slowly, at least we know that these humble steps that we make are steps we make in the right direction.

[…]

The Saints themselves, as long as we are surrounded by their community, they are fighting for us. And they are going to give us the crown of victory. Because we might perceive ourselves as failures in relation to them; we might feel humble in relation to them; but how humble must they feel in relation to the perfect one: Christ our God?

This struggle that Peterson relates, to believe in something so terrible, and the obligations it seems to present which would be so incomprehensible to bear, can be softened by the wisdom and example of the saints and the love of God, if we can only see it, as Fr. Seraphim says, through this lens.

But it is nonetheless a terrible thing indeed, which makes the crisis we are enduring all the more severe. May God have mercy on us.