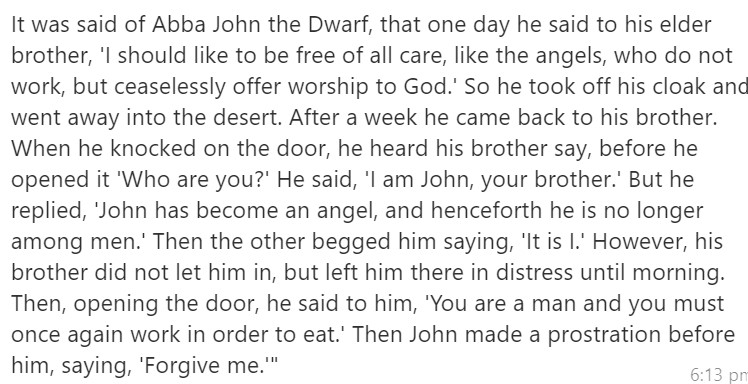

For we are sojourners before thee, and strangers, as were all our fathers. Our days upon earth are as a shadow, and there is no hope.

A Good Day for Starting Over: Doing the Thing

Fr. Cassian [of the Benedictines of Norcia] gave me a copy a while back of the guide used by some of the monks of Norcia to schedule their Lectio Divina – that covers the whole thing in two years, and follows the liturgical cycle – and I’ve given it a shot a couple of times, and of course it’s fallen aside each time. I’m more regular with the Office but even that needs to be pumped up a bit. (Ok, it needs to be pumped up a lot.)

The Marian antiphon starting from Candlemas (today) changes with this season of penitence to the Ave Regina Caelorum. Here are the words and the simple tone, so you can sing along if you like. What is an “antiphon”? I’m so glad you asked…

The start of Septuagesima, as I mentioned on Sunday, is in effect another of the liturgical year’s little mini New Years. It’s the start of our prelude to spring. We’re back to the start of the liturgical year again, the Easter Cycle of our great True Myth. In a sense, it is the start of our time of preparation for all new things, new births and great changes, the putting off of the tired old year, the tired Old Man.

“Put off your old self, which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful desires…And… be renewed in the spirit of your minds and… put on the new self, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness.”

And I think we can find a little solace this year that it starts so early. The Christmas Cycle can have as many as six Sundays after Epiphany, if Easter is set as late as it can be – that is, if the Resurrection and rebirth of all good and true things are delayed as long as possible. This year we have as early an Easter as the calendar admits, with only three Sundays after Epiphany. Maybe this can be taken as a little sign from God, or at least as a reflection of how we all feel this year – Haste! Haste! Lord! Rescue us! We are perishing!

The old calendar and liturgy reflects this as the start of a new beginning, making Septuagesima Sunday the day we re-start the reading of the Bible in the Matins readings of the Roman Breviary: “Here beginneth the Book of Genesis… In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth… And so on, and that which followeth…”

But how can I actually do that? How can I just decide to sort myself out? Truth to tell, I’m a mass of conflicting mental and emotional interior forces. I want to work more, do more drawing, be more regular in all the important building blocks of my life; prayer, work, exercise, gardening, socialising… And I ask myself all the time, why am I not? Why can’t I make myself Do The Thing? What is this mysterious mental force field I experience so often, something I almost bounce off when I try to do things?

It’s Not Just You

Why don’t I work more? Why don’t I pray more? Why don’t I do the one thing that will pretty much guarantee success? Why don’t I do what I need to do to know God? What is this strange force that stops me, and how can I defeat it?

In part, it is a result, plain and simple, of the Fall:

We know that the law is spiritual; but I am unspiritual, sold as a slave to sin. I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do, I do not do. But what I hate, I do. And if I do what I do not want to do, I admit that the law is good. In that case, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it.

I know that nothing good lives in me, that is, in my flesh; for I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do. Instead, I keep on doing the evil I do not want to do. And if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it.

So this is the principle I have discovered: When I want to do good, evil is right there with me. For in my inner being I delight in God’s law. But I see another law at work in my body, warring against the law of my mind and holding me captive to the law of sin that dwells within me.

What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? Thanks be to God, through Jesus Christ our Lord!

So then, with my mind I serve the law of God, but with my flesh I serve the law of sin.

Romans 7:14-25

It does mean you’re responsible, of course. But it also means absolutely everyone struggles to Do The Thing. At least a little, in some area of life, and that God has taken this weakness into account. In one sense knowing this allows you to give yourself a little bit of a break. You’re not uniquely lazy or useless or in any way doomed to failure. And you are Not. At. All. abandoned or unlovable because of it. You are, in fact, no different from everyone else. So, get that idea out of your head right away.

Partly at Fault are Our Modern Notions of Artists

Psychologists are looking at this universal human problem in the struggles artists have with making themselves do the work, and are making some headway. They’ve identified this complaint of St. Paul – that can be a problem for any kind of endeavour from cleaning your eaves troughs to praying the Divine Office – and called it “resistance.” And like “stress” before it, it has been shown to be a real Thing and not just some dumb excuse people use for being lazy and worthless.

[See this video which Youtube has prevented us from embedding for more on this point.]

The short form is, “Ignore all romantic nonsense about ‘the muse’. If you are finding you can’t Do The Thing, there’s more to it than some moral failure or failure to be ‘a real artist’. You’re experiencing something real but complex, that has been made exponentially worse by the way we have set up our culture, and that absolutely everyone experiences. The good news, however, is that there are things you can do about it and it doesn’t mean you’re a ‘failure’. Basically if you’re still alive, you haven’t ‘failed’ yet and we reject the devil’s counsels of despair.”

From the video above:

Radiating off that screen like radioactive magma would be a negative force saying, “Let’s not do this today. Let’s go have a drink. Let’s go to the beach. Let’s do something else.” And it would also say things like, “Who do you think you are to tackle this project? You have no experience. No one cares about your ideas. Everything’s been done before…”

[…]

Overcoming resistance is far more important than talent, or anything else.

There’s a lot of self-help literature working on this problem now, and offering good, concrete ways to overcome resistance and its consequence, procrastination.

I won’t get into it here, but it’s pretty much what you’d expect: identify the problem; knock down your fear by breaking tasks into small bits; keep lists of things to do, but also things you’ve accomplished… (Really, it’s not that hard.)

Art is Work and So is Prayer

A lot of the difficulty we have with Doing The Thing – whatever the thing may be – is the way our culture lionises and even to an extent mythologises “artists”. As I’ve said many times, since we gave up on education we have created this myth of the artist-as-superhero or wizard, someone just naturally endowed with some kind of superheroic gene that allows them to render a scene or a figure with a pencil – a kind of magical ability like the Harry Potter magician gene that ordinary Muggle-mortals don’t have.

Now we say that the “artistic impulse” just happens to you, like winning a lottery or getting struck by lightning, and that’s what it takes to create something. This means making things or doing things is not something you do – an action of your will manifested by physical activity – but something that just happens to you. And quite honestly, this one nonsense-myth has probably done more to disrupt our civilisation’s creativity than any other, causing the almost paralytic stagnation we are now suffering. We turn “artists” into magic superheroic celebrities, superior beings who live in a kind of alternate universe from us, and do nothing ourselves because of it.

We have, in a sense, taken the making of art (of any kind including what we might call the “spiritual arts”) out of the realm of human action entirely, and this has robbed us of hope. We can’t aspire to something that is by nature unreachable unless by sheer chance, so in the hopelessness created by this false picture, we give up and don’t try.

The Paradox of Sanctification

“Am I too late? Am I too slow? Am I too sinful? When the Saints depress us with their perfection”

The more we advance spiritually the less we feel that we have made any progress. The grace that we were given initially…is being lifted. Or at least we perceive it as being lifted. There comes a time when God wants us to to learn how to deal with temptations.

…and by opposing, end them.

One Becomes a Saint by Doing the Things Saints Do

It is certainly how most Christians view the saints – as angels who don’t have to try – and it’s definitely what I thought of the saints when I first returned to the practice of the Faith. I just figured they were people specially picked by God for His attention, for reasons of His own, and the rest of us poor ordinary schlebs just had to muddle along and hope to get to heaven as best we could. The idea that one could “become a saint” was something that I guess I’d heard of, but had absolutely no idea how to begin approaching. In fact, I figured it was like the artist thing; just something that happens to you if you’re extraordinarily lucky.

I thought my responsibility was to avoid sin and the near occasion of sin as best I could, receive the Sacraments regularly, and learn all I could about the teaching of the Church – and that it ended there.

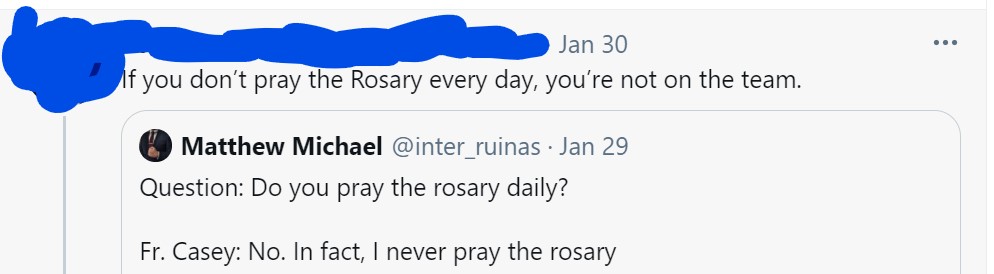

I was also deeply wary of the people who promoted their favourite devotions like they were magical talismans – say such and such a prayer (always given by an angel or the Virgin Mary to some visionary no one ever heard of) twice a day on alternate Tuesdays – that just seemed a half inch away from pure superstition. And invariably along with that kind of quasi-magical, mechanistic devotionalism comes the spiritual illness – the neurosis – of scrupulosity. It’s the religious version of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, in which the vengeful legalistic rubricist in the sky will smite anyone who steps out of line, isn’t in the club or “on the Rosary team” – who forgets or fails to say the magic spell on the appointed days…

Anyone who doesn’t know the in-club’s secret handshake is doomed:

What any of that had to do with the God or the Faith I’d heard about was a mystery. A lot of the people I know have fallen down that rabbit hole, becoming obsessed with visionaries, Marian apparitions, “prophecies” and all manner of quasi-gnostic flummery, and all who have, even if they managed to climb out again, have been harmed spiritually and psychologically. To this day, I run the other way if someone starts telling me in earnest and conspiratorial tones the details about how “our times” were described by their pet visionary.

Weren’t the Sacraments Enough?

Well, yeah, but no. There’s this thing that hardly anyone ever talks about: dispositions. The human heart is really the only unbreakable safe in the universe. It can only be opened from the inside. (In fact, of course, He can break in, but won’t.) Your job is to meet God’s efforts to reach you by taking a step or two – however hesitant – on your own (or by even being willing to try). You need to do something, and it’s pretty small, on your side to make your soul capable of receiving and benefiting from the sacramental grace on offer.

Until I started receiving spiritual direction at the Toronto Oratory, where I started learning these things, I was frustrated and confused by the obvious fact that I was doing the things I thought I was supposed to be doing, and was still a mess. It was almost enough to make me think what everyone thinks – that sanctification is something special only for the already-special.

Treating the Sacraments as though they work automatically -without any input from you – is akin to treating them like magical talismans and God as a kind of pez-dispenser machine. If you are a daily Communicant, but you do nothing else, never pray, never do any interior work, the grace of the Most Holy and August Sacrament of the Altar, that can transform you, won’t. It will bounce off your thick shielding of indifference and concupiscence (and very often presumption and sometimes… God save us… spiritual pride) and all your customary faults and awfulnesses.

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and a contrite heart,

O God, You will not despise.

Three Ways

It wasn’t until I read a book by the late Fr. Thomas Dubay, about Carmelite spirituality, that anyone even suggested that there were things you could – and must – do, beyond the basic thing, in order for the process of sanctification to even begin. Of course, I knew I had to stay as best I could in a state of grace – the Oratorians are very big on weekly confession – and receive the Sacraments. But I didn’t know what most Catholics don’t know; that this is only the foundation. That there is a whole business of the Interior Life that had to be embarked upon; and I think it is the absence of any form of Interior Life – or even knowledge of its existence – that is doing the damage to the Body of Christ that we can see, most starkly, on “Catholic Twitter” every day.

Fr. Dubay was the first place I’d ever heard of the idea that there was a well-laid out process of sanctification – that saints knew about and spiritual directors used to talk about. I was overjoyed to discover this, because it put the lie to the miserable idea that sanctification was magic or random and something I had no power to do myself.

In the Western Church, it is called the Three Ways of the Interior Life (or as it was called by the great Dominican theologian, Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, “The Three Ages of the Interior Life“) and always follows the same pattern, no matter what spiritual tradition you’re finding it in. First you work to purge your sins and faults. And of course this means finding out what they are, for which a spiritual director, or at least a good confessor is really needful. The more you can do that, the closer to God you can grow in mental prayer. Then God Himself steps in and raises you up to the heights. The third “Age” – that has been called the “Transforming Union” – is what we see in the saints. That’s “sanctification” – union with God.

(Here’s something to think about though; there isn’t a moment in which He really does leave you alone to figure things out. Your desire to know, your inability to leave it alone and stop wrestling with Him, is an indication that He is there and you are already doing what you’re supposed to be doing. It’s worth considering that the old Desert Fathers used to always call the desire for and pursuit of sanctification by a completely different name: “the struggle” or “the combat”. If you’re struggling, you’re on your way, by definition, because it means that God is prompting you. The only way to lose here is to give up and walk away and not care.)

St. Benedict

In the Benedictine tradition we don’t really focus so much on the end result – that’s more a Carmelite thing, whose ideas always struck me as about as appealing as reading a calculus textbook before bed time. The Benedictine way is more about the process, since no one has any real idea of where they are from the perspective of heaven anyway. It’s pointless (and can be dangerous) to worry your head about what “stage” you’re at. The point of the whole thing is lost if you’re thinking about yourself and which “mansion” you’re in now, right?

The “purgative way” part – the ousting of faults, habitual sins and evil habits of thought – is considered to be taken up by the demands of formation and community life – covered by the second of the Benedictine vows, Conversatium Morum, “conversion of life”. This includes all the aspects of daily life, community living, manual work, the following of the Rule. (Btw: that’s not something that ends, at least not in this life. So it’s not like you get it all squared away, you’re all tidied up, so it’s time for the next phase. It all kind of keeps happening together… which is why Benedictines are kind of not that into systems.)

The cornerstone of Benedictine spirituality, prayer, is the meditative praying of the Divine Office, mostly made of the Psalms, and Lectio Divina – “divine reading.” Our “system” was first codified formally in the 12th century by a Carthusian monk named Guigo. He wrote about the “Ladder of Monks” naming the four steps of contemplative prayer as “lectio,” (slow reading of the Scriptures) “meditatio,” (thinking and learning about them) “oratio,” (succumbing to the irresistible urge to lift your mind and heart up to God) and “contemplatio” (God’s answer to you).

If it still sounds complicated, you can remember what Fr. Prior said when I asked him how to do “Lectio”. He said, “Well, I don’t know how the other brothers do it, but I take the book and read a little bit. Then when I feel I’ve got something to chew on, I think about it.”

Our Spiritual Impoverishment

I had been aware for years that I didn’t have the full story, but no one I asked told me about this, and this was the reason I couldn’t figure out what was wrong with me. There was a kind of logical gap between what I knew about myself, my failings, my sinfulness, my inability to change myself, and the radical sanctity I saw in the lives of the great saints. How do you get there from here? It seemed there was a chasm and I couldn’t find a bridge. I guess I knew in a vague way that becoming a saint had something to do with prayer and “being good” – but I still understood that only as “saying prayers”. I was a step or two above the child-level of prayer as just “asking for things” -as though God is a kind of heavenly Amazon delivery service. But vocal prayer was still all I knew about.

I had heard that saints (and monks and nuns) spent hours and hours every day – often whole nights – “at prayer” but couldn’t figure out how one did it. Didn’t you run out of things to say? Still burdened somewhat by my neurotic fears that God would reject me if I Did It Wrong, I started pursuing approved prayers I was finding in old books. This was actually a pretty good start, since much of the old devotional literature for laypeople is really, really instructive. But it still felt like not enough. It took me quite a while longer to learn the missing pieces.

It’s not about talking. And it’s definitely not a recitation of a shopping list of requests. God isn’t a divine mail order catalogue. Not a machine. Not there to give you things. Still less is He a divine Stasi officer waiting to pounce on you for wrongthink (an idea that is wretchedly common among us North American Anglo /Irish/German Catholics who think the Faith is a matter of intellectual pursuits, political arguments and rubricism).

My fundamental lack of understanding what prayer is was hardly uncommon. This is the realm of Mystical Theology, and in our times when the only two aspects of Catholicism anyone ever hears about are The Rules and Politics; the lost secrets of mystical union with God are… well… lost.

Unless you meet monks.

Read, and live; taste and see. “Contemplation is the sweetness itself which gladdens and refreshes”

Guigo:

Reading seeks for the sweetness of a blessed life, meditation perceives it, prayer asks for it, contemplation tastes it. Reading, as it were, puts food whole into the mouth, mediation chews it and breaks it up, prayer extracts its flavour, contemplation is the sweetness itself which gladdens and refreshes. Reading works on the outside, meditation on the pith [soft inner part of a feather or a hair; the essential part, core, heart]: prayer asks for what we long for, contemplation gives us delight in the sweetness which we have found.

Knowing God isn’t what we think it is. It’s not making supplication to a tetchy perfectionist, waiting to find fault and condemn us. It isn’t like reading rules and regulations.

In fact, it’s a lot more like poetry than you imagine, which is why we meet Him so well in the Psalms. It’s why so much of the words of the prophets are like songs.

Guigo again:

For the sweetness of a blessed life:

Reading seeks;

meditation finds;

prayer asks;

contemplation tastes.Reading, so to speak, puts food solid in the mouth,

meditation chews and breaks it,

prayer attains its savour,

contemplation is itself the sweetness that rejoices and refreshes.Reading concerns the surface,

meditation concerns the depth

prayer concerns request for what is desired,

contemplation concerns delight in discovered sweetness.

Where Hope is, There is God

But there’s one aspect that I am only starting to grasp now and that is hope. It’s easy enough to see that the world is horrible and getting worse. We rightly fear what we see happening. But what do we hope for? How do we even know to hope for something so completely unprecedented in the world?

It is in the example of Christ Himself and the lives of His saints where we can even find out what to hope for. It’s where we look to identify clearly what this thing is that we can only dimly sense is missing. It is this mystical union of the soul with Christ that the extraordinary feats of courage and indifference to the world come from that we read about in the martyrs and saints; their feats of extraordinary endurance of suffering and selflessness that are called “heroic virtues”. (And of course all the fancy stuff like levitating, prophesying, stigmata and wonder-working, but that’s all a bit beside the point.)

All the things we read about in these peoples lives that make us almost despair, because we don’t know how they did it. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that it’s hopeless; I can never be like that, and if that’s what it takes, I’m sunk. But this is thinking like the world. It is forgetting that the saints themselves did not reach these heights by their own powers.

In one sense, no, you definitely can’t get there from here. From the position of trying to “be good” and never embarking on the great quest for radical perfection that God carries you though. Union with God, with Christ the Divine Bridegroom, changes you in ways you can’t really picture now. And of course to even begin to understand what this is like is why we need the examples of the saints in the first place.

We need most desperately this hope: that God is good; that Christ died to save us; that God loves us radically and persistently; that He helps us rise up to Him because He knows we cannot climb alone; and there is a way to heal all the hurts the world has struck us with.

Without this hope, we can’t even want to know Him. And I think this is where all of this ties in with where I started. “Resistance” in psychology is very much tied up with fear. We fear that we will be disappointed, that our hopes will be for nothing. The more evidence the world seems to present that we are deluding ourselves by hoping for good things, the more fearful we become; and in the end, a world enveloped in the darkness of fear will be all we believe in.

This “resistance” – this fear that we are NOT loved, that we don’t have anything to hope for, that we not only can’t achieve our goals for this life, but that there is no meaning to any of it because God is not really the God we hope for… This is the resistance I know stops me from praying, and from working, and from Doing All The Things. I’m not afraid I can’t do it; I’m afraid there’s no point to trying.

And this is the worst crime of all that the New Paradigm of post-Conciliar Catholicism has committed: to have erased all knowledge and memory of this path and to tell us nothing about the Real God. It condemns us, if not to hell in the next life, then at least to a trudging sense of hopelessness in this one. And it heaps temptations to despair and even to “curse” God as unknowable, as an unfair gamester who holds up impossible ideals and then punishes us for failing to meet them.

We don’t need more regulations or more rubrics. We don’t need more “Theology on Tap” nights. We definitely don’t need any more online lay YouTube Catholic celebrities telling us who to vote for. If this is all they’ve got, it can’t be surprising that people are walking away. They offer no hope.

What the Church needs is not more politics, but this secret “Ladder of the Monks” that sets out a clear path to follow, a stair to climb, to rid ourselves of our bitter resentments, and fears and despair.

The preceding was originally published at the author’s site, Hilary White Sacred Art. Hilary makes her living painting works of sacred art by commission along with the occasional essay about the process of producing said art, or about living the faith in the modern world. We hope you will support her efforts there as a patron of her artwork and/or her writing.