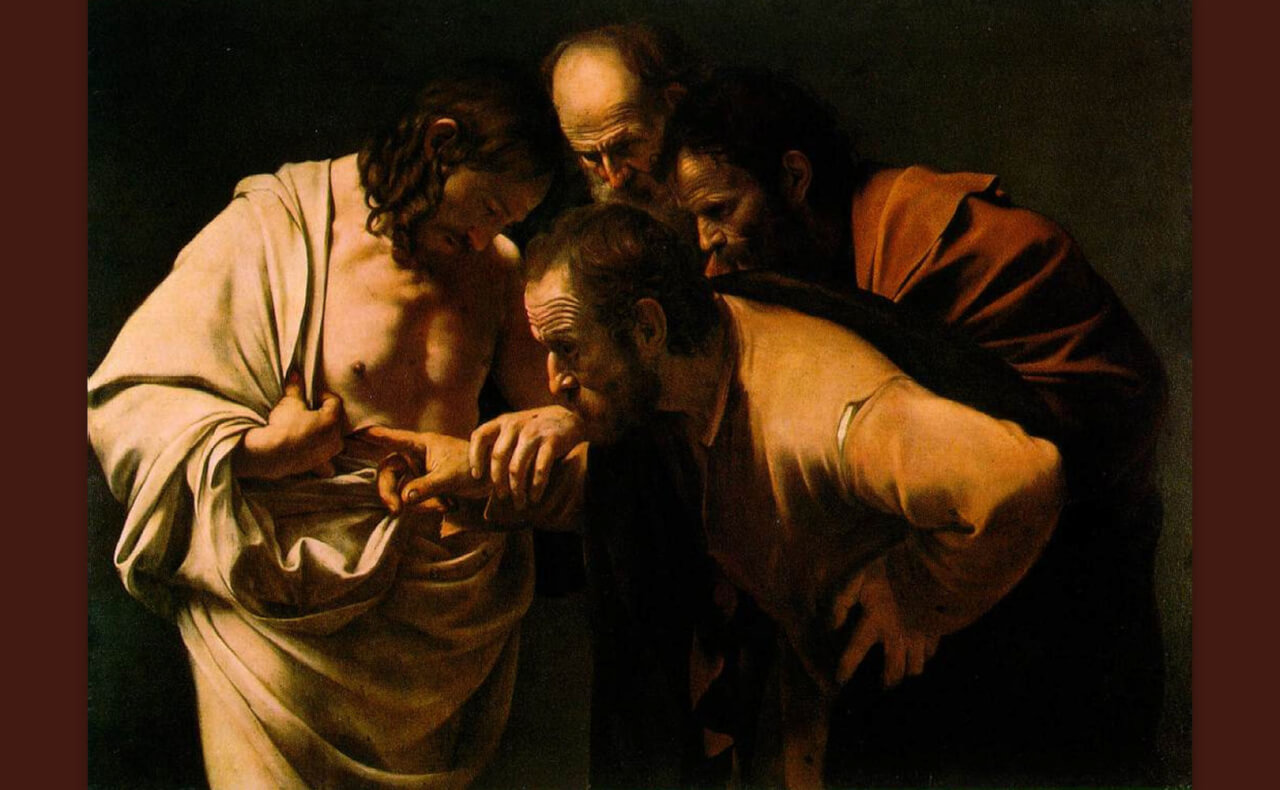

This past Sunday, the Gospel reading was the story of “Doubting Thomas”, taken from John 20:19-31:

At that time, when it was late the same day, the first of the week, and the doors were shut, where the disciples were gathered together, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood in the midst and said to them: “Peace be to you.” And when he had said this, he shewed them his hands and his side. The disciples therefore were glad, when they saw the Lord. He said therefore to them again: “Peace be to you. As the Father hath sent me, I also send you.” When he had said this, he breathed on them; and he said to them: “Receive ye the Holy Ghost. Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them: and whose sins you shall retain, they are retained.”

Now Thomas, one of the twelve, who is called Didymus, was not with them when Jesus came. The other disciples therefore said to him: “We have seen the Lord.” But he said to them: “Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails and put my finger into the place of the nails and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

And after eight days, again his disciples were within, and Thomas with them. Jesus cometh, the doors being shut, and stood in the midst and said: “Peace be to you.” Then he said to Thomas: “Put in thy finger hither and see my hands. And bring hither the hand and put it into my side. And be not faithless, but believing.” Thomas answered and said to him: “My Lord and my God.”

Jesus saith to him: “Because thou hast seen me, Thomas, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen and have believed.”

Many other signs also did Jesus in the sight of his disciples, which are not written in this book.

But these are written, that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God: and that believing, you may have life in his name.

After reading the passage, I found myself involuntarily returning to it, turning it over, feeling that it was laden with particular meaning for our time. This image of Thomas, one of the twelve, who despite having been told (John 2:19-22 and Matthew 16:21-23 come to mind) that Jesus would rise again after his death, could not bring himself to believe that it had happened without proof.

I have often thought about the apostles on Good Friday and Holy Saturday. About how they must have felt. Is there any question that they must have been assailed with doubts and temptations about Our Lord? About this cause — this man — that they had given their life to? They knew Him to be a worker of miracles, multiplying food and healing the sick and raising the dead — but surely, if He was the Son of God He would not have allowed Himself to be brutally humiliated, tortured, and killed.

Perhaps upon hearing the news of His crucifixion they even fought amongst themselves about what more they could have done to stop it all from happening.

Jesus, of course, had warned them that they would doubt Him. He told Peter that he would be so scandalized, he would deny Him thrice in one night. At the time of His agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, He took with him only “Peter and the two sons of Zebedee” (Matthew 26:37). The mystic Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich tells us that Our Lord chose to bring only these apostles for good reason. In her vision of the Dolorous Passion, she quotes Our Blessed Lord as saying:

Call not the eight; I did not bring them hither, because they could not see me thus agonising without being scandalised; they would yield to temptation, forget much of the past, and lose their confidence in me. But you, who have seen the Son of Man transfigured, may also see him under a cloud, and in dereliction of spirit; nevertheless, watch and pray, lest ye fall into temptation, for the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.’

If they were to feel this way watching Him suffer as he prayed in anticipation of His passion and death, what must they have felt after His Passion was consummated, and He was laid in the tomb?

St. Thomas, it seems to me, manifests the fullness of this sentiment when he refuses to believe what he cannot see and touch for himself. It is not clear from the words in the Sacred Scriptures, but it does not take much imagination to read anger into his words: “Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails and put my finger into the place of the nails and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

One could almost imagine him thinking, I was already fooled once when I believed in and followed this man, and now look where that’s gotten me! I won’t be taken in again.

One of our readers recently commented about his correspondence with an unnamed “important prelate of today”. He says that the cleric in question responded to one of his requests asking what would be done about the present crisis in the Church by saying that we really can’t do anything but to “pray, to suffer with the Church on her Good Friday, to proclaim the truth courageously and with love. The rest we have to leave to the Lord, and He will intervene, because it is His Church, not ours. … Otherwise it will be a too human action and will not be blessed by God. We have to accept the Golgotha hours of the Church and suffer with her and trust in the Divine intervention.”

For this reader — in truth, for many of us — this answer feels woefully insufficient. Like Thomas, we struggle to accept what happened at Golgotha, and our powerlessness before such a tragedy. “It’s great that they had another conference in Rome to address the reality of the crisis,” people might say, “but when are the faithful bishops and cardinals going to do something?” We saw this same lament echoed by the conference attendees last weekend, who, during Cardinal Burke’s presentation about papal authority and its limits, spontaneously began to chant: “We are waiting! We are waiting!”

Waiting for what?

For action. For more than words.

It’s a sentiment I understand. If something can be done, I think it must be done.

But at the same time, I keep thinking about St. Thomas and his stubborn indignation. Whereas Peter refused to accept that Christ really had to suffer and die — earning him the famous rebuke, “Get behind me, Satan!” — Thomas refused to believe that He had really returned from the dead as He had promised He would. He knew Our Lord was dead and buried, and he was living with the shock and the scandal of that. When the apostles told him Jesus was back, he just couldn’t believe it. It seemed too far-fetched. He knew what was empirical — that this man they had given up everything to follow had been beaten to a pulp and nailed to a cross until He was dead. All that power, all those miracles, all the talk about His Father in Heaven, and He had been wiped out like the petty criminals crucified beside Him.

Thomas was almost certainly still struggling with and grieving Our Lord’s death; the idea that He had already risen from the dead was probably something he just couldn’t wrap his mind around until Jesus confronted him face to face. Not even his friends could convince him.

What was St. Thomas doubting? It seems to me that he doubted that Christ would, after all, fulfill the promises that He had made. He doubted that when it appeared that all was lost, God would — or could — overcome the impossible. Perhaps, then, he even doubted that Christ was ever who He had claimed to be in the first place.

Are these not the very same temptations we face today?

We’re watching the Mystical Body of Christ — the Church — endure her own passion and crucifixion. “How can this happen?” We ask. “If this is really the Church of the Son of God, why doesn’t he take her down from the cross and save her?” Didn’t He promise us that the gates of Hell would not prevail? But just like on that first Good Friday, God is not coming to the rescue. Not yet. And because it’s not happening, we begin to waver. To doubt. We are tempted not to believe that Christ will preserve His Church. We can’t even imagine how He would do so unless we act. Unless we take control. And if there really isn’t anything we can do except prayer and suffering — except enduring the via crucis — it’s really not surprising that we can’t anticipate how this gut-wrenching spectacle will end. And like Thomas, we won’t be able to do so until we’re on the other end of it, probing the nail wounds with our fingers, placing our hands in the Church’s side.

“Blessed are they that have not seen and have believed.”

Do we believe? Can we overcome our doubts? Can we trust that He has a way out of this — one we can’t see — and that He doesn’t need our intervention to preserve the Church from defeat at the hands of the enemy? Can we bear to wait and wonder, not knowing what comes next or what our place is, believing He will, when the time is right, come to the aid of His mystical bride?

There was a plaque in one of the offices where I used to work, inscribed with one of the favorite sayings of the owner of the company: “Don’t confuse activity with achievement.” We want to be busy. We want to get our hands dirty. We want to be engaged in the work of righting this ship. And to be honest, I can’t imagine God will blame us for trying. But we mustn’t allow ourselves to believe that this crisis will end at our hands. And by us, I mean by the hands of men. Not just laity, but also bishops and cardinals. By resigning ourselves to the reality that we have no greater role than praying, we are demonstrating our faith that the only one who can save us — God — is He in whom we place all our trust.

Perhaps it’s true that our shepherds should take more drastic action. Perhaps it’s true that if they fail to do that, they will be held to account. But that is theirs to discern. We can urge them, pray for them, and cheer them on, but they will not save the Church. God will. There is no other way out.

I have often said that I suspect this crisis will reach a point where we have become so desolate, where there is so little hope of an answer, that when the solution comes, there will be no question in our minds that it is from God himself.

This is not a consoling thought. Not in the short term. But we have to prepare ourselves for the possibility that there is nothing else we can truly expect. We cannot allow ourselves to doubt that the Church is what she claims to be simply because it appears that the gates of Hell have prevailed. We must not believe that even if Catholicism as we understand it appears to wind up in the tomb, that this is the end. Jesus has not left us room to disbelieve that He has the power to conquer anything, even death.

Until then, we continue our watch. We continue to “work like everything depends on us, and pray like everything depends on God.” But we must “put not our trust in princes” — not even princes of the Church.

And until the stone is rolled away, “the rest we have to leave to the Lord, and He will intervene, because it is His Church, not ours.”

And like the things not recorded in the scriptures after Jesus’ Resurrection, perhaps these, too, will happen “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God: and that believing, you may have life in his name.”

When it is all said and done, when we finally see the resolution, when God’s saving power restores the Church to glory, we, like Thomas, will have no choice but to fall on our knees before Him, declaring, “My Lord and My God.”