Editor’s note: This article is written from a temporal and linguistic perspective oriented toward the Novus Ordo. We elected to publish it as an introduction to a musical subject that may be more comprehensible to those of our readers less musically inclined from an English-language standpoint. The basic principles herein apply to the Latin Mass and its calendar and feasts.

A music major who takes a good “history of music” course at a university music department will encounter the term “word painting” when studying the music of the Middle Ages (and Gregorian chant as the most important music in the West in that era).

Word painting is an illustration, in musical melody, of the meaning of a word that is sung on that music. One of the most famous examples is found in Handel’s “Messiah.” Toward the beginning, the baritone sings a powerful solo, a melody on words from the prophet Haggai (2:7) about the coming of the Messiah: “and I will shake all nations, and the desire of nations shall come.” To illustrate how God will shake the nations, Handel created one of the most blatant examples of word painting in all of music: in singing the word “shake” (on the vowel sound in the middle, the “a” of shake), the singer must sing long descending phrases of melody that illustrate perfectly the feeling of being powerfully shaken. It is almost as if the audience is suddenly experiencing an earthquake through the music. In this, the audience has just encountered word painting. (One has only to listen to the beginning few minutes of the Messiah, after the overture, to hear this.)

There is another outstanding example of word painting, from among many in Handel, in his secular oratorio “Semele.” The action of hurried flying through the skies is painted or depicted, when the goddess Hera tells her servant Iris to “fly to the realms of day” in her aria “Hence, Iris, Iris Hence Away!” On the word “fly” (on its vowel sound of “y”) the singer sings long lines of melodic notes, and these succeed in not only depicting flying, but doing so in a great hurry.

Gregorian chant is the origin of all of this, and it depicts in melody not only actions and objects, but also abstract concepts and words like “hope,” “mercy,” and even the name of God.

For example, in more than one Gregorian Agnus Dei, the word “mercy” is often suitably painted. The painting here uses a device that is piece of “sign language” in a number of Gregorian chants. The word “mercy” is set on two connected arches (lines) of musical notes, which seem to signify grace, or God’s descent into the world as Christ. (God’s name is often set on a single upward arching line, or half circle, of music — but mercy or grace is signified by two arches, descending.) In this way, the word “mercy” communicates more than what the word alone says. We are given a form and feeling for mercy.

Why paint or illustrate the meaning of words in melody in this way? The answers are several. Put succinctly, it is so human intelligence can grasp something in a new way. This is very important when trying to grasp or understand the Word…and the words that make up the Word.

A number of Gregorian chants paint the act of placing, putting, setting something down, or sitting down, in the same way — using short successions of notes (motifs) that are like the action of a hand lifting up and putting something down.

(The four motives combine, moving down each time — perfect for a group sitting down.)

(In this case, the three motives together are depicting something being “in place,” starting with “God,” higher up, and then “in” and “place” lower down.)

It at first seems improbable that any music could make use of an intelligible language. But this is perhaps easier to imagine when we remember that there are sign languages — like that used by the deaf or by those keeping silence. Sign language is capable of expressing almost as well as speech. Sign language is a combination of three things: motion, lines, and shapes. The reader has probably never stopped to think that musical melodies have all of these as a feature. Music always takes place in a time frame and always “moves” forward from beginning to end. (In fact, we seem to be stationary as music passes by in time.) It is certainly true that music is perceived to “move” and that it has “motion.” Thus, music possesses one of the key factors of any sign language: motion.

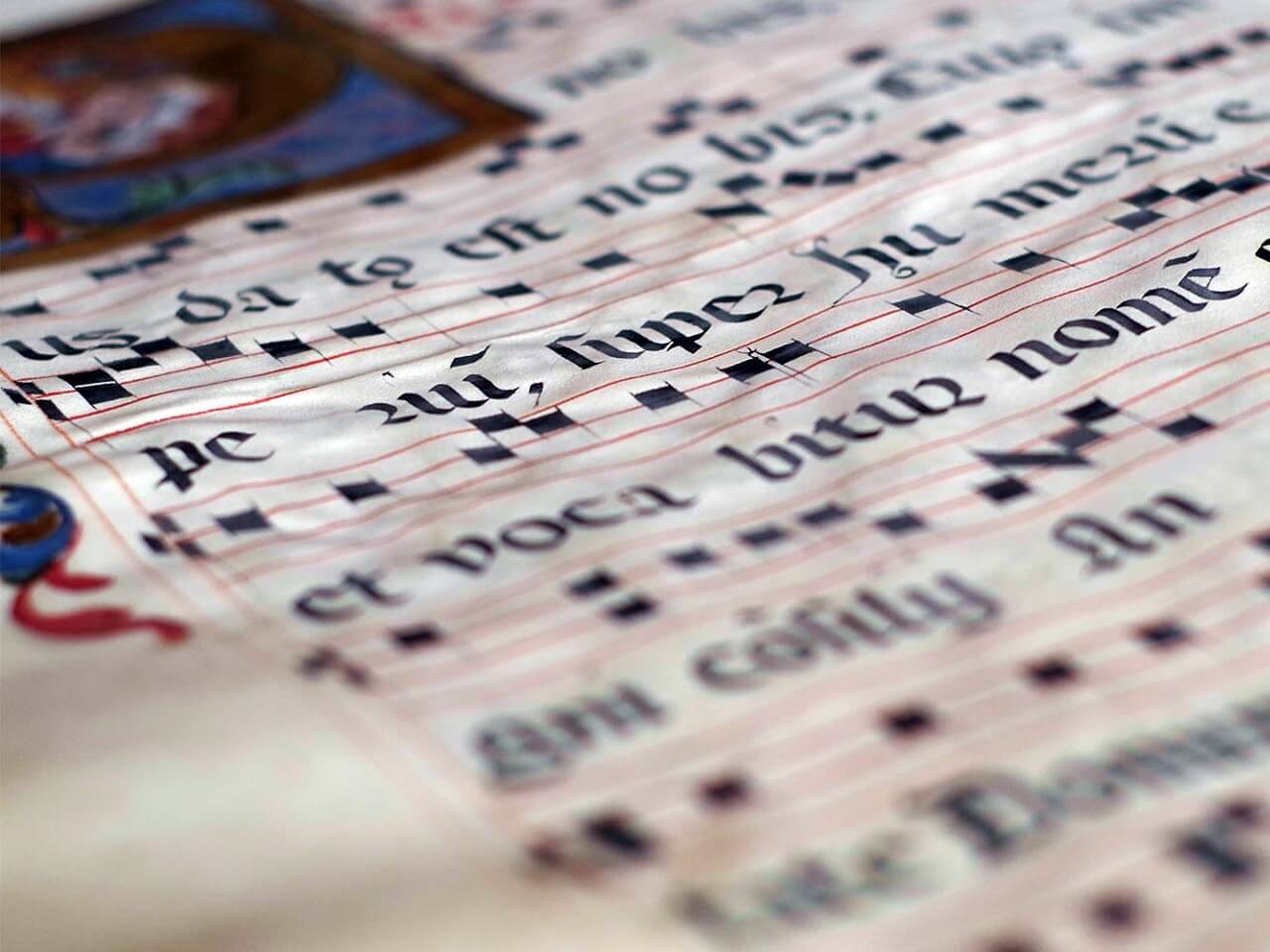

Music, in the course of its motion, always creates “lines.” This is immediately visible if one looks at a piece of sheet music. The eye is drawn to lines of notes in the notation of the music. Not only on paper, but in hearing live music, the mind links successions of notes to one another and perceives them as a line. The notes in a piece of music make strings of notes, like people standing in line. In this way, music has the second element of sign language: line.

In sign language, shapes are made out of lines, and the same is true of music. The rise and fall of the lines in music make shapes. Music always partakes of rising and falling, in myriad patterns. There can be such shapes in music as arches, semi-circles, open-ended squares, rectangles, triangles, staircases upward and downward, long flat lines, verticals, waves and wavy lines, etc. This is the third element of sign language: shapes.

Considering that music has the three capabilities needed for sign language — motion, line, and shape — it should now come as no surprise that music can partake of sign language. Music can move, make lines and shapes, and talk sign language. This is exactly what is going on in the “word painting” of Gregorian chant. There is no other musical form in the world that goes as far into this as does Gregorian chant. Western European opera is the second-place winner (in regard to painting specific words).

That said, how common is word painting in music? In Gregorian chant, it is extremely common. One reason that is not so easily noticed is that Gregorian chants are in Latin. When true Gregorian chants are reset properly into one’s own language — in our case, English — the word painting becomes much more apparent. This is the raison d’être behind PAINTED CHANT: An Annotated Mass Book of Gregorian Chants in English (available from Amazon books). In it, Gregorian chants are transcribed into English, using an editorial method that preserves the word painting — a first in terms of translating Gregorian chant.

Almost every Gregorian chant uses word painting. In the beginning pages of PAINTED CHANT is given a “dictionary” of just some of the words that are painted in the chants found in the volume. Here is a sample from the two-part dictionary:

Illustrations of actions or objects:

| all | 13th Sun, Offer., all the judgements |

| altar | 5th Sunday (I will go in to the altar of God) |

| bow down | (Psalm 65, all the earth shall bow down) |

| cedar | (shall grow like the Cedar of Lebanon) |

| Cherubim | Trinity Sun. Grad: and sits above the Cherubim |

| Church | Peter and Paul I will build my Church |

| clap hands | (clap your hands all you peoples) |

| crucified | (for our sake, He was crucified) |

| depths | Trinity Sun. Grad: Who looks into the depths |

| disturbed | 11th Sunday, offer., I shall not be disturbed |

| earth | Pentecost, The Spirit of God replenishes the face of the earth |

| ends | 14th Sun Ent. to the ends of the earth |

| flee | Pentecost, entrance “flee before His face” |

| flourish | (The just man shall flourish like the palm tree) |

| go | 12th Sun I will go and offer up |

| grow | (shall grow like the Cedar of Lebanon) |

| honey | Corpus Christi, and with honey from the rock |

| in | 14th Sunday who hopes in Him |

| highest | (Glory to God in the highest) |

| lamb | (Lamb of God) |

| looks | Trinity Sun. Grad: Who looks into the depths |

| on | Peter and Paul and on this rock |

| palm tree | (The just man shall flourish like the palm tree) |

Abstract words:

| blessed | Trinity Sunday, Grad: Blessed are you o Lord; |

| 14th Sunday blessed is the man | |

| Christ | Kyries 1–4, Christ have mercy |

| created | Pentecost, and they are created |

| dwell | 17th Sunday, Those who dwell in His house |

| for | (for our sake, He was crucified) |

| for (therefore) | 4th Sun., for they shall see God |

| generation | (You have been our refuge from generation to generation) |

| God | 14th Sunday , Offer., my King and my God |

| good | 14th Sunday that the Lord is good |

| his | Christ the King Communion His people |

| insult | Sacred Heart, offer., in insult and misery |

| is | 14th Sunday that the Lord is good |

| holy | Sanctus, Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Hosts |

| judgements of your mouth | 13th Sun., Offer., all the judgements of your mouth |

| known (scrutinized) | 11th Sunday, Offer., who has known me |

| Lord | Trinity Sunday, grad., Blessed are you o Lord |

| 14th Sun, Offer., to you I pray o Lord | |

| misery | Sacred Heart, Offer., in insult and misery |

| peoples | 13th Sun., All you peoples |

Now that the reader may understand the prevalence of word painting, we may ask again, as we asked above, why should Gregorian chant be so concerned with words and musical meaning? The answer could fill half a book, and we won’t go into it fully. Gregorian chant as a Christian art form involves setting the words of Scripture and liturgy to music. Not only is it setting words; it is setting the Word to music. In the process of setting the Word to music, it is only natural that making the words of Scripture intelligible in a new and enhanced way is a fascination. If music can open up another door into the Word, and cause the performer or listener to actually enter into the Word in some new way, this is an amazing gift, and perhaps one of the true meanings of the gift of music to humankind.

Certainly, various art forms have been used to great effect to communicate many things about God, the Church, and God’s Word as found in Scripture. One has only to think of stained glass, statuary, icon paintings, or the architecture of churches to understand that the Word is communicated in many ways.

The fascination with setting the Word to music in Gregorian chant, as in the other arts, has to do with intelligibility and intelligence itself. Words obviously are understood by the intelligence. Thomistic theology of God as understanding or intelligence is relevant to our discussion of music that paints words. What if music itself can be read by intelligence, like words? And what if this added, further appeal to intelligence through music can cause human intelligence to grasp the word, and the Word, in an expanded way? Our understanding, participating in the intelligibility of words and music, is enhanced in understanding the Word, which is surely God’s intelligence.

Word painting in Gregorian chant is painting not only concrete words and visible actions, but also abstract things. (The painting of abstract things, like “mercy,” was approached above.) In the following antiphon from one of the commons of the Blessed Virgin Mary, both concrete things and abstract things are portrayed. The word “carried” is a concrete action and is quite suitably depicted — as one might depict carrying something in sign language.

In this chant, the abstract word, “eternal,” is also depicted. How is this done? First of all, there is a musical jump up to the notes of phrase, and the phrase then continues on the highest notes in the chant. This means to say, purely in terms of note pitches, that this is something “on high,” something awesome. The line present, which is described by the motion of the music, is somewhat like a wave, with one of the middle points in the wave elongated. Somehow, this leap up on high to an elongated wave seems quite appropriate to communicate the idea of eternity…

There may arise some skepticism regarding the painting of abstract words. The extent of word painting in Gregorian may be questioned, and a skeptic may ask, “How do you really know that a melisma of 11 notes on the word ‘eternal’ is really painting something? What is it painting?”

This leads to an interesting point. By what faculty does a person understand the painting of an abstract word? It is somewhat visual, like looking at someone doing sign language, but it is more than that as well. We can answer the questioner, “It is painting, through its line and height, the idea of eternity.” But some further perception is called for.

In fact, some new perceptive faculty may be opened up for the purpose — which may well be called intuitive but might also be thought of as the mind under the influence of revelation or the Holy Spirit. There may be some people who at first do not find this faculty when exploring Gregorian chant. However, a little guidance may go far in alerting the participant in singing or studying chant as to what is in it.

Illustrations and analyses of word painting examples could fill a series of books, and we can only include few more examples here and add that this discussion of words and the Word, intelligence and God’s intelligence, relates to St. Cecilia, the patron saint of music. St. Cecilia, among other things, represents a tradition about music in the Church. Basically, this tradition could be understood to say that music is capable of bringing the hearer of, or participant in, music to the doorstep of contemplation of the Divine. What we have just said above about word painting, intelligence, and God as intelligence now sheds light on this ancient tradition.

As the reader will see from the examples of word painting that follow, Gregorian chant offers a doorway into a new realm, where the intelligence understands words and the Word in a manner enhanced by music. Since Thomists will agree that God, in His very Being, is pure intelligence or understanding, the claim that Gregorian chant is a uniquely Christian art is all the more valid, since the chant brings us, through an enhanced understanding, closer to the Word and the Divine intelligence. There is no other musical art in the world that does this, except parts of oratorio and opera.

One additional point about Gregorian chant: word painting is done in more ways than one. The sign language we have described above is one essential part; another is mood and affect created by the musical scales or modes used. There is an exposition of mode and scales given in the appendix of the PAINTED CHANT, put there because it is easier to understand for musicians.

One of the places where mood can paint words more successfully than does sign language is in the Kyrie, when the word “Christ” is painted in long melismas. One might say illustrating the word “Christ,” unless one is going to try to draw a man in sign language (and then how would you show what kind of man he is?), is best done by evoking spiritual moods. There is one Kyrie that sets the word “Christ” over a long melisma where the mood that comes from this music — if it can be put into words at all — is something like “the water of life being turned into wine.” This word painting by mood makes for a most beautiful form of art music.

Most of the simplified English chants used today do not have melismas longer than three notes. It is very difficult to paint any word with only three notes, although sometimes the pitch of such a short phrase may paint a word. For example, if the three highest notes in a whole chant fall on “heaven”, then that word may be said to be “painted” in some degree. Generally speaking, simplified chants used today eschew word painting in the process of eliminating melismas of more than three notes.

If one surveys the chants found in the Liber Usualis, it seems that certain parts of the liturgy lend themselves best to certain kinds of word painting. The most lavish word painting by sign language is found in the propers of special feasts, especially those of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The most poetic “mood word painting” is found in some Kyries. The most mystical and abstract word painting is found in the Sanctus.

Word painting has long been understood and taught in music history courses at universities. But we have found examples of it that are extraordinary in the course of producing this work. The distinction of concrete and abstract subjects in word painting is useful to point out, because, once the inquirer understands the painting of abstract words, he is coming close to understanding the general spirit of Gregorian chant. And not only that, but he will be able to understand that some chants are, in their whole forms, the painting of larger abstract ideas. The most amazing cases, in this author’s opinion, come in the setting of the Sanctus.

The Gregorian chants of the Sanctus, nos. 2 and 3, are based on the image of angels singing the Sanctus in Heaven. Much of the imagery is achieved through the levels (heights) of pitches. In Sanctus 2, the chant is set low in pitch, as if one is looking down from a high place (from the standpoint of the singers — who are the angels, there is only what is below). This is a sort of “mystical” reversal from what one would expect — which would be to have the entire chant very high in pitch. But that would be seeing the angels from our point of view, below, on Earth. These chants place us with the angels.

Sanctus No. 3 is set low. The highest pitches are reserved for “heaven” and “He who comes,” showing a similar emphasis on Jesus as higher than the angels (and us, the singers of the chant).

The following, and final, example is about as elaborate and artistic as Gregorian word painting can become. In the first lines of this gradual on Psalm 90, the words “our refuge” and “generation” are painted with long lines of notes. “Our refuge” is set on 32 notes, “generation” on 35 notes.

The word painting in this part of the chant communicates the imagery of God being our refuge, as well his timeless help from generation to generation. The music attaches an actual emotion or “affect” to these words, through its shapes (lines) and phrasing. The whole of this particular chant on Psalm 90 (the above is an excerpt) is so full of word painting and correlations among the shapes used that it leads one to consider that writing a Gregorian chant like this may have been the approached the same way as icon painting was approached. The painter of the icon prays and fasts, so that the Holy Spirit may speak through the painting.

With all of the above understood and laid out, the reader is here invited to experience this musical word painting in Gregorian chant, by listening to it and even by singing it. A new prospect presents itself: the possibility of people at Mass entering into this world of Gregorian music and returning to the shelter of St. Cecilia, where music leads to the doorstep of contemplation.