|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

At OnePeterFive we have attempted to probe the depths of the crisis beyond Vatican II and see the roots of many of the problems with Vatican II and its aftermath going back to the 19th century. Hence our emphasis on combatting the clericalism of the 19th century with the Two Swords doctrine and opposing hyperüberultramontanism – which is merely a species of clericalism – with the traditional doctrine of the Papacy. The Novus Ordo disaster is a result of things that were going on before Vatican II.

This is why the pre-1955 Holy Week matters.

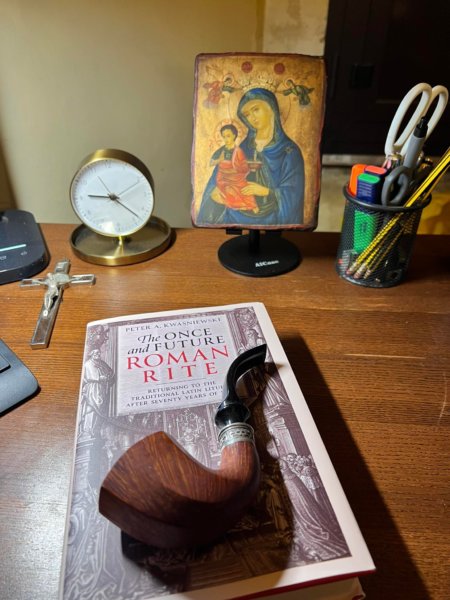

Dr. Kwasniewski, in his monumental tome on the Roman Rite, summarises his years of passionate liturgical research this way:

Catholics in search of tradition have for many decades now favored a return to the 1962 Missale Romanum and its related liturgical books, prior to the landslide of change that followed the Council. Yet these liturgical books fall squarely within a period of accelerating mutation that already bit hard into the substance of the Tridentine inheritance: the new Easter Vigil of 1951, the new Holy Week of 1955, the new code of rubrics of 1960, and so forth. All of these were interim projects preparing for the “total reconstruction” or instauratio magna (to use a phrase from the philosopher Francis Bacon) that took place in the decade following Sacrosanctum Concilium of 1963. In a period of chaos, the Missal of 1962 has been a “rock of stability,” as Michael Davies once called it, but it is also an island on which one cannot camp out permanently.

When, exactly, did a chaste love of gentle reform became an unbridled passion for novelty? Some put the blame on Pius X for his major modifications to the course of psalms prayed by the Roman Church from the earliest centuries. Others would single out Pius XII for throwing his weight behind a commission of liturgical reform that gave Annibale Bugnini his first Vatican position and gave the world a mutilated Holy Week, its quondam grandeur shattered by incoherence. Still others point the finger at John XXIII for his modification of the Roman Canon and for his naïveté in summoning an ecumenical council crowded with blinking bishops and progressive propagandists. Most, however, would squarely name Paul VI the destroyer par excellence who could not rest until he had seen the inheritance of millennia dismantled and rebuilt in modern fashion. Do we not see, all along, a papal predilection to overreach, to indulge a monarchical Petrine power of remaking the Church’s worship, when, as most of papal history shows, the popes have rather been its grateful recipients, vigilant defenders, and reverent adorners? Should not the popes, above all, see themselves as servants of the great patrimony that has been handed down to them, rather than judges of its supposed defects and manufacturers of its latest model? Is it too much to ask that they be “guardians of tradition”?[1]

In Kwasniewski’s chapter which dismantles the imprudent reform of Pius XII (pp. 333-375), he adroitly provides the historical connections:

Pius X reordered part of the Roman rite’s prayer; Pius XII refashioned the heart of the Roman rite’s year; Paul VI replaced the entire Roman rite with a modern rite.[2]

The uncomfortable fact that must be faced by Trads is that St. Pius X and Ven. Pius XII are critical players in the overall Novus Ordo programme under which we now suffer. Since Papa Sarto’s reform was to the divine office, it did not directly affect the laity (for the most part). The reform of Papa Pacelli however, was nothing less than an assault on the most cherished customs and devotions of the laity. We can see this in particular in the endurance in many dioceses (even without the Latin Mass!) of the custom of praying Tenebrae in the evening during the Triduum. This custom was assaulted when the Roman Pontiff forced the Catholic world to celebrate Holy Thursday in the evening.

As Pius XII himself says in Mediator Dei, it is the right of the Pontiff to “introduce new rites” (58). This is indeed true, no doubt. Yet the Pope’s first duty is to guard and preserve Tradition. If papal infallibility is defined this way regarding “no new doctrine” at Vatican I, then this holds, a fortiori, for the lex orandi.

If the Pope wishes to introduce some new liturgical rite for pastoral reasons, this is entirely legitimate… in theory. But this must be done in a way that first preserves the existing tradition. In other words, it has to be optional.

Pius XII could have merely introduced the new Holy Week at every Cathedral of every diocese – and left every parish freedom to adopt it, or not (or better yet – why not introduce it as an option in your own diocese of Rome only?). Then the new Holy Week could have been a legitimate option for Catholics who wished to celebrate these new rites. That would have been the pastoral thing to do, which respected the customs of liturgy while introducing something new for some grave cause. This would both preserve the existing tradition and introduce a new rite legitimately.

But if the Pope wishes to force the laity, in the most important days of the liturgical year, to abandon liturgical and devotional tradition in favour of the Pope’s new rite, then this is ultra vires. Plain and simple.

Pius XII did that.

Paul VI did that too.

Because of the plague of clericalist hyperpapalism, it seems that the Popes of the 19th and 20th century adopted the Liberal bureaucratic model of the secular state, imposing on millions of faithful their new rites and ideas, ignoring subsidiarity and local custom (this is what makes this different than Quo Primum). It seems like the Popes were trying to be the bishop of every diocese.

Now to be fair, as we have said, the Popes were also fighting manfully against the Liberal assault – both in ideas and bloodshed – and many indeed (the saints among them) were doing their best.

But the traditional movement must come to terms with this aspect of our history, and the laity should seek to recapture the cherished traditions of our forefathers for Holy Week. This includes not only the liturgies of Holy Week, but also the devotions and customs, some of which were attacked by the forced reform of Pius XII. To this end we have good online resources like Restorethe54.com as well as pre-55 printed materials like the Father Lasance Missal and the Blessed be God prayer book, as well as a new text from Os Justi Press: The Masses of Holy Week & Tenebrae. And as Kwasniewski mentions above, this is not just about Holy Week. The 1962 Missal has other issues as well, and the next big one is coming up as Eastertide comes to a close – the Pentecost Vigil.

But at the same time if we are being consistent here, we should also advocate for the pre-55 Holy Week as an option to be restored. The 1962 Missal has passed into local custom in various places, and should not be disturbed except for grave cause. The ancient Holy Week should be restored as a free option to be adopted by individual parishes if they so desire.

In other words, I believe that the traditional movement should be trying to achieve the model of pre-Trent liturgical diversity, not hoping for a mythical Pius XIII to impose the Pre-55 Holy Week on everybody. That would be using the same hyperpapalism to achieve an imagined ideal. That is the modern Papacy. We want the traditional Papacy, which guards local custom, and the authority of the local bishop.

We have to remember that the ends do not justify the means, even if we like that Trad fantasy world that results. An extreme act of Papal tyranny would be the same thing Pius XII did except in reverse.

Yet More

Yet we must always remember – especially in this new period since “Jailers of Tradition” (Traditionis Custodes) – that we must unite the clans.

It’s fine to entertain the opinions above in theory and in academic books, but there’s another reality we must face now as Trads which in one sense is even more urgent.

Especially in the holiest week of the year, we must remember the words of Holy Thursday:

Ubi cáritas et amor, Deus ibi est.

V. When, therefore, we are assembled together.

V. Let us take heed, that we be not divided in mind.

V. Let malicious quarrels and contentions cease.

V. And let Christ our God dwell among us.

Hear the words of the Holy Ghost: there is a thing which the Lord hateth, and the seventh his soul detesteth… [it is] him that soweth discord among brethren (Prov. vi. 16, 19). What good is it to offer a “liturgically perfect” service with rancour in your heart toward your brother? Indeed such worship is rejected by Almighty God. Let us not condemn other Trads for their liturgical options and opinions about the liturgical controversies of Holy Week. Let us rather hold our opinions less strongly than we hold communion in the Mystical Body of Christ.

Indeed, as our contributing editor Eric Sammons wrote cogently, “Tradition is a means to an end.”

The perfect Holy Week is an offering of a contrite heart for my sins which caused the death of Christ. If my “perfect liturgy” does not achieve that in my heart, then no amount of tradition and incense will help me escape the fires of hell.

[1] Peter Kwasniewski, The Once and Future Roman Rite (TAN: 2022), xxiv-xxv, emphasis added.

[2] Ibid., 334.