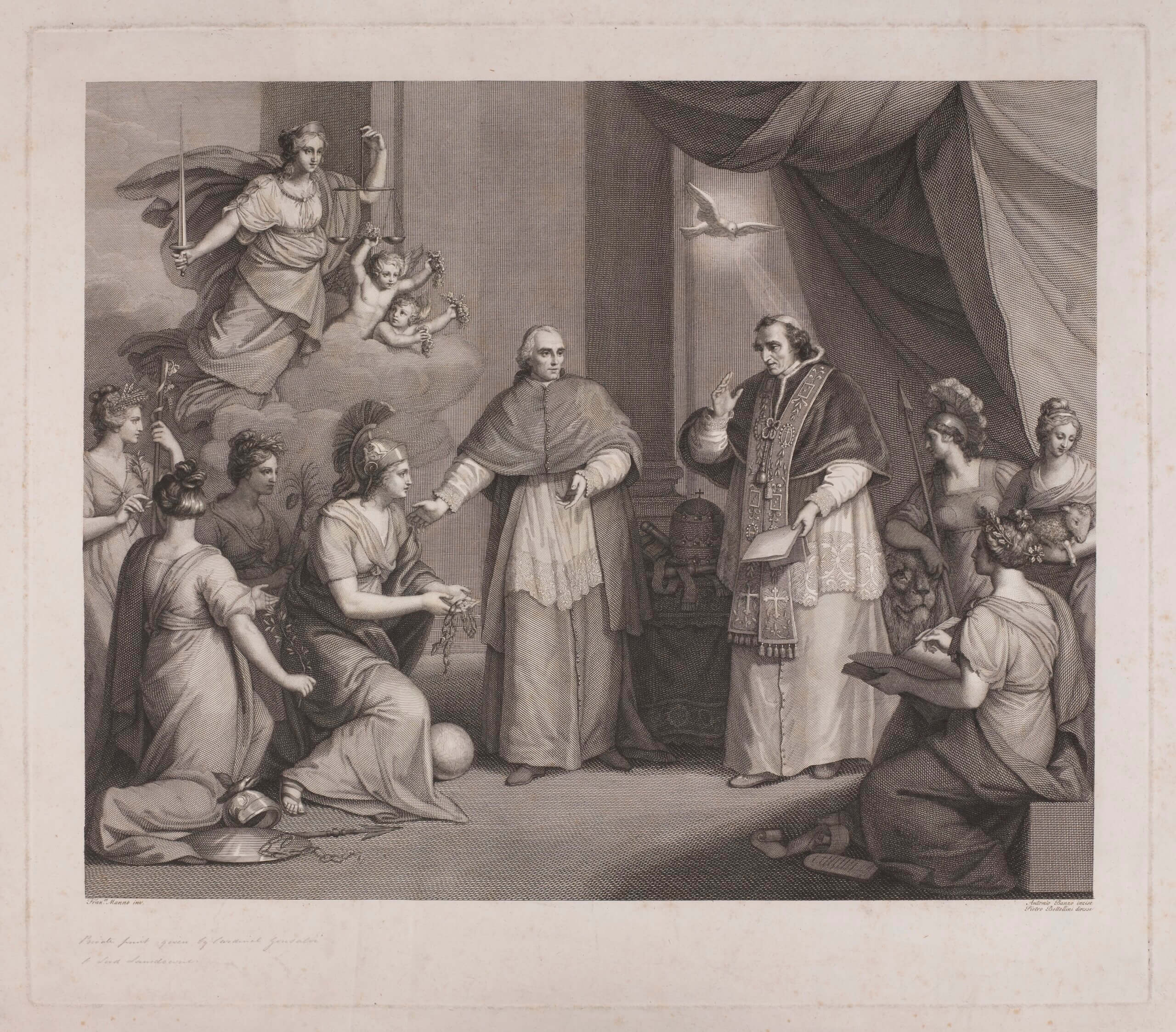

Above: the restoration of Rome and the Papal Legations by Cardinal Consalvi to Pope Pius VII after the defeat of Napoleon. Engraving by A. Banzo after F. Manno

It is said that once, to Napoleon Bonaparte († 1821), who threatened to destroy the Papacy and the Church, a man replied, “Your Majesty, you would be making a useless effort. You would be defeated. We, the priests and Christians, with our weaknesses and infidelities, have not succeeded in destroying the Church! And would you like to do it?”

That “man of genius,” as he was defined by an Anglican scholar, was Cardinal Ercole Consalvi, Secretary of State to Pius VII from 1800 to 1806 and from 1814 to 1823, who died two hundred years ago today, on January 24, 1824.[1] He remained perhaps the most famous of the Secretaries of State to His Holiness, the Pope’s first collaborators in the governance of the universal Church. In addition to the episode just mentioned, Consalvi is remembered, among other things, for the concordat he concluded in 1801 with the then first Consul for the French Republic, Napoleon Bonaparte, in Paris and for the large territorial restitutions to the Papal States that he obtained in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna.

Born in Rome on June 8, 1757, a student at the Seminary of Frascati (1771-1776) and at the Academy of Ecclesiastical Nobles in Rome (1776-1782), he was a pious ecclesiastic and faithful to the Pope, alongside Pius VI (1783-1799) and especially close to Pius VII (1799-1823), “both of whom were torn violently from their episcopal see and taken to exile.”[2] Like Cardinal Giacomo Antonelli († 1876), Secretary of State to Pius IX, Consalvi was never ordained a priest, remaining simply a deacon. He was a delicate person of soul and determined in character, with an innate inclination towards the fine arts and a strong love for poetry and music.

In particular, he studied the violin, an instrument that would provide him with pleasure and distraction from state affairs throughout his life. He also became a great friend, admirer, and protector of Domenico Cimarosa († 1801), one of the greatest composers of the eighteenth century, as well as one of the last great representatives of the Neapolitan musical school. Precisely because of this true and profound friendship, many of Cimarosa’s musical manuscripts were not lost; many of them were donated by the maestro to the cardinal and carefully preserved by him.

Consalvi was saddened by “the death of my very dear friend Domenico Cimarosa, the first, in my opinion, among composers of music, both for his creativity and for his knowledge, just as Raphael [† 1520] was the first among painters. He died on January 11th in Venice while composing his famous second Artemisia there, which he couldn’t even finish.”[3] The cardinal had a solemn mass for the repose of his souls in the Roman church of Sts. Blaise and Charles in Catinari on January 25. The Missa pro defunctis in G minor, which Cimarosa had composed and performed in 1787, as soon as he arrived in St. Petersburg, was performed “by all the musicians who were in Rome and who participated for free.”[4]

Consalvi then ordered a bust of Cimarosa (today in the Capitoline Museums) from Antonio Canova († 1822); finished in 1808, it was placed next to Raphael’s tomb in the Basilica of Sancta Maria ad Martyres (Pantheon), of which the Secretary of State was Cardinal Deacon.

His musical culture allowed him to actively intervene in the programs of the Cappella Giulia, the choir of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. Three episodes confirm this. In the first two, the canon prefect of music Angelo Costaguti tells us of Consalvi’s predilection for Niccolò Zingarelli († 1837), who between 1805 and 1812 had been director of music of that choir. The first concerns the music decided for June 29, 1816:

On the day of St. Peter’s Eve, Cardinal [Ercole] Consalvi, Secretary of State, sent for me and asked me to perform Zingarelli’s Psalm Laudate during the Great Vespers instead of that by [Pietro Alessandro] Guglielmi [† 1804]. I told him that he would be served, and since in my role as prefect I don’t depend on anyone, therefore, without breathing a word to anyone, without asking anyone, I gave the order to the archivist that Zingarelli’s Psalm Laudate be performed, as it was actually performed.[5]

The second summary relates to the feast of Saints Peter and Paul in 1817:

On the morning of June 25, 1817, Cardinal [Ercole] Consalvi sent for me to find out from me what music I was making in St. Peter’s. I showed him the list, and he told me to do Zingarelli’s Laudate, even more so when he knew that Zingarelli had sent a new solo and sextet. Everything turned out well.[6]

For the solemn Vespers of June 29, 1819, in which eighteen cardinals participated,

it had been previously decided to change the Psalm Dixit set to music by Pitoni in 16 parts, into one by maestro [Pasquale] Anfossi [† 1797], and the Psalm Credidi by Burroni [Antonio Boroni († 1792)] into that by […], but when Cardinal Consalvi, the Secretary of State, became aware of this, he ordered the usual Vespers to be sung and nothing to change, which pleased everyone.[7]

An esteemed statesman? A music lover? Certainly! However, we want to remember Cardinal Consalvi as a faithful servant of the Holy See, a cleric of authentic faith with an intense spiritual life. I hope that this small introduction achieves this end, in its small way.

[1] J. N. D. Kelly, The Oxford Dictionary of Popes, Oxford 1986, p. 303.

[2] Benedict XVI, Speech, October 4, 2008.

[3] M. Nasalli Rocca di Corneliano ed., Memorie del cardinale Ercole Consalvi, Rome 1950, p. 61.

[4] F. Florimo, Cenno storico sulla scuola musicale di Napoli, Naples 1869, p. 459.

[5] G. Rostirolla, La Cappella Giulia 1513-2013, Bärenreiter 2017, p. 832.

[6] Ibidem, p. 848.

[7] Ibidem, p. 863.