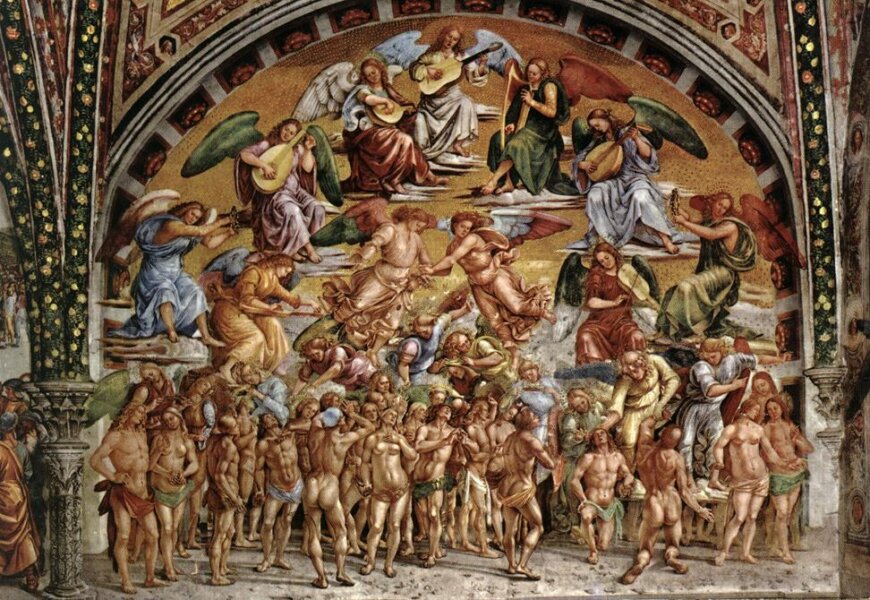

Above: the San Brizio Chapel.

Five centuries ago, on October 16, 1532, “an excellent painter,” Luca Signorelli, died. He “was more famous throughout Italy in his day, and his works were held in greater price than has ever been the case with any other master at any time whatsoever.”[1]

Born around 1450 in Cortona, central Italy, and educated there, around 1470 he moved to Arezzo, where he was a pupil of Piero della Francesca († 1492). Signorelli often went to Florence and regularly saw Verrocchio, in whose workshop Leonardo († 1519), Botticelli († 1510), Ghirlandaio († 1494), and Perugino († 1523) had trained. In the Vatican, he painted, among other things, the Testament of Moses fresco from the Sistine Chapel cycle (1481-1482). In the Abbey at Monteoliveto Maggiore, near Siena, he worked on the grandiose fresco cycle of scenes from the Life of St. Benedict (1497-98). The splendid decoration of the Cappella Nova or chapel of San Brizio, in the right transept of the Cathedral of Orvieto, central Italy, carried out from 1499 to 1504, constitutes the masterpiece of the artist from Cortona. Signorelli finished the decoration of the vault, begun in 1447 by Blessed John of Fiesole (Fra Angelico), and completed that of the entire chapel.

There is so much music in his paintings! Let’s consider eight of them.

In the Altarpiece of Sant’Onofrio, dated 1484, we find an angel tuning a lute in the center. The angel’s left hand unscrews the peg while he plucks the string with his right thumb, and his ear searches for the right pitch. Giorgio Vasari writes about it: In Perugia, also, he made many works: among others, a panel in the Duomo for Messer Jacopo Vannucci of Cortona, Bishop of that city; in which panel are Our Lady, St. Onofrio, St. Ercolano, St. John the Baptist, and St. Stephen, with a most beautiful angel, who is tuning a lute.”[2]

In the celebrated canvas School of Pan (1490), painted for Lorenzo de’ Medici († 1492) and destroyed in Berlin in 1945, we notice a syrinx, or Pan flute, resting on the knee of the goat god sitting in the center. Each of the characters surrounding Pan plays a fistula (the ancient wind instrument used by shepherds) of different lengths.

In the Adoration of the Shepherds (1496), at the top right, we find a bagpiper intent on performing some Christmas pastoral. Of the ancient wind musical instrument, you can just see the wineskin full of air in which some reeds of different lengths are inserted.

In the Madonna and Child with Saints (1519-1523), preserved in the National Museum of Medieval and Modern Art in Arezzo, we find some stringed instruments. At the bottom center, you can see King David plucking the psaltery to accompany the psalms; at Mary’s sides are two musician angels, the one on the left with a lute and the one on the right with a viola da braccio (arm viola). We can almost hear the concentus angelorum, already present in the works by Fra Angelico.

The Assumption of the Virgin (1519-1520), coming from the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Cortona and kept in the Diocesan Museum of Cortona, fully expresses the concentus angelorum, a great polyphony with very refined counterpoint. The angels are arranged symmetrically, five on each side. On the left, three angels play the lute; a bearded character next to the Virgin plays the dulcimer; a little further down, we see an instrument leaning on the left shoulder of another angel. On the right, you can see three more lutes; the angel below seems to notice the imperfect pitch of the other lute above, so much so that the player prepares to tune his instrument while playing. At the top right, we find a flat-bottomed instrument with a bow. In the center, still on the right, near the Virgin, you can see a tambourine without a membrane with a double row of rattles around it.

Now let’s go to the Cathedral of Orvieto. In the San Brizio Chapel (above), Signorelli

painted all the scenes of the end of the world with bizarre and fantastic invention — angels, demons, ruins, earthquakes, fires, miracles of Antichrist, and many other similar things besides, such as nudes, fore-shortenings, and many beautiful figures; imagining the terror that there shall be on that last and awful day. By means of this, he encouraged all those who have lived after him, insomuch that since then they have found easy the difficulties of that manner.[3]

In the upper part of the Resurrection of the Flesh, we find two long trumpets which, adorned with the banner of the risen Christ, cease to participate in the angelic concert to call the dead to judgment.

On the left side of the Ascent to Paradise, four musician angels accompany the elect into the holy city, the heavenly Jerusalem, with the sound of their instruments, three with plucked strings and one with wind instruments.

In the scene of the Blessed in Paradise, the instruments are so varied as to project us into the spiritual harmony that the blessed regain in music inaudible to the human ear, even the most educated and cultivated one.

Also thanks to Luca Signorelli, the biblical word has become image, as well as music. How many, especially believers, and in times when few could read or write, have gained from it! A pedagogy founded on St. Gregory the Great’s words in a letter of 599 to Serenus, Bishop of Marseilles:

Painting is employed in churches so that those who cannot read or write may at least read on the walls what they cannot decipher on the page.[4]

May this centenary be an opportunity to see the artistic heritage of painting and music, as well as that of sculpture, architecture, and mosaic, placed at the service of the mission of the Church.

[1] G. Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects.

[2] Vasari, ibidem.

[3] Vasari, ibidem.

[4] Epistulæ, IX, 209: CCL 140A, 1714.