Editor’s note: the following is the first part in a series (see part two here) from our friend Hilary White, originally published at her new site, Hilary White Sacred Art. We hope you’ll visit her there for more about her discoveries in the ancient traditions of Western and Byzantine sacred art as she transitions from making her living primarily as a news writer to one as a painter of sacred art.

Featured Image: carved wood icon of St. David of Wales by Aidan Hart

What does the common expression mean, “pursuit of holiness”? We hear it a good deal from churchmen, but the details, the concrete “how-to” is often left vague. Most of us have never heard anything about the Church’s great traditions of contemplative prayer – mostly assuming they are intended for monks and nuns. We know “go to Mass” and “pray the Rosary,” but little more. In the US and Canada, Eucharistic adoration is popular, but I don’t remember ever being taught how to pray before the Blessed Sacrament. And about “mental prayer” I never heard a single word.

If you only get your information on the spiritual life and how to conduct it from sermons at Mass it’s easy to come away with the idea that it is a rather nebulous, undefined (perhaps undefinable) and has something to do with “being nice,” an answer that can’t help but fail to satisfy.

It’s especially unsatisfactory to people who develop a healthy sense of their own sins and shortcomings. If that’s all there is to it, how is “being nice” going to change me? How do I get transformed from being a sinner into a saint? Or even just less bad? And crucially, what has it got to do with Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross, His death and Resurrection? Anyone can “be nice”; it doesn’t take God Incarnate to be a Saviour for that.

And this gap is filled very often with a lot of nonsense. New Age and warmed-over Eastern mysticism (often much to the annoyance of actual Hindus and Buddhists) is offered by popular “spiritual writers,” available in parish and monastic bookshops across the globe. And it need hardly be said that a good deal of this – pertaining as it does to one’s eternal destiny – can be very dangerous indeed.

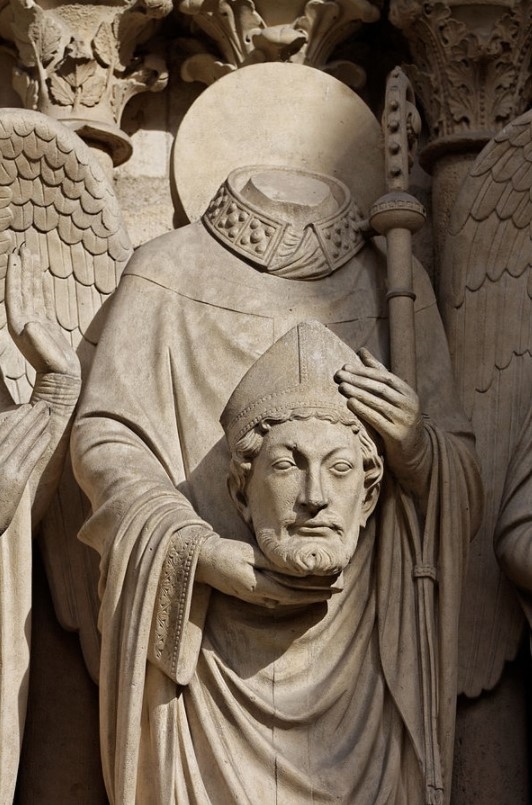

And what of the saints? If “being nice” is all that’s expected of the general run of humanity, what does that mean for the Church’s great history of saints? Doesn’t it hint that in fact, sanctification – the real thing, that produces the miracle workers, the walkers-on-water, the raisers-of-the-dead, the healers, the levitators? How do you go from “being nice” to laughing off being grilled to death for Christ? To failing even to notice being rent by wild beasts or strapped to a post and set on fire in the arenas of 3rd century Rome and Carthage? What does “being nice” even have to do with someone like St. Denis, who was martyred by beheading? He who famously shrugged it off, got up (or at least, most of him did), picked up his head, stoically tucked it under his arm, and marched off to carry on preaching and calling sinners to repentance. (This is actually a thing. So much so that there’s a name for it in Christian hagiography: “Cephalophore” – Greek for “someone who carries his own head around, and not on his neck.”)

Such stories, we might be tempted to think, are in the realm of heroic fiction. They read like Homeric myths of monsters and demigods. What could they possibly have to do with us? Or with “being nice”?

Very little examination is required to conclude that there has to be more to it.

But then the question arises; if that’s so, then how do I get there? It seems like there is an impassable gulf not only between me and God, but even between me – regular old me down here on unremarkable planet earth living my lumpy quotidian life – and my fellow man who has somehow mysteriously achieved these exalted heights. If the “be nice” doctrine is true, the only sensible response to the saints is a shrug and a hearty “Well done you!”

This puzzle started occupying my mind when it occurred to me that not only must there be more to it, but that no one was telling. (This is because most of the people in charge of the Church in our time don’t know either.) And this brings me to the video linked below, about the life of St. David of Wales:

This is one of a series of biographical videos made by a group of Orthodox Christians in the US, called “The Chronicles of the Desert”. It’s a series that mostly focuses on the saints of the first millennia, the ones that the Catholics and Orthodox have in common. These are the guys, like St. Anthony the Great, who marched off to the Egyptian wilderness to emulate Moses and Elijah, to have face to face encounters with the living God. So, how then does David of Wales fit in to this “desert” business? Anyone who has taken a summer holiday in Wales will tell you that the place is hardly a desert. And yet, St. David was firmly of that ancient Christian mystical tradition that we sometimes abbreviate to “the desert”.

So what does “the desert” mean in the context of the pursuit of sanctification? I’ll let you watch the video, and think about this: all saints enter the desert. St. Philp Neri, the wonderworking “second apostle of Rome,” who never left Italy in his life. St. Columbanus, the mariner and founder of Celtic monasteries. St. Cuthbert, the abbot of Lindisfarne who spent his life in Northumberland. Bl. Anna Maria Taigi, the married mother and housewife who lived a suburban life in Rome and was a mystic of the highest order. All the same. All saints of the desert.

In the next installment, we’ll talk about this concept more, and explore how mental prayer is the door to a whole other world. Stay tuned.