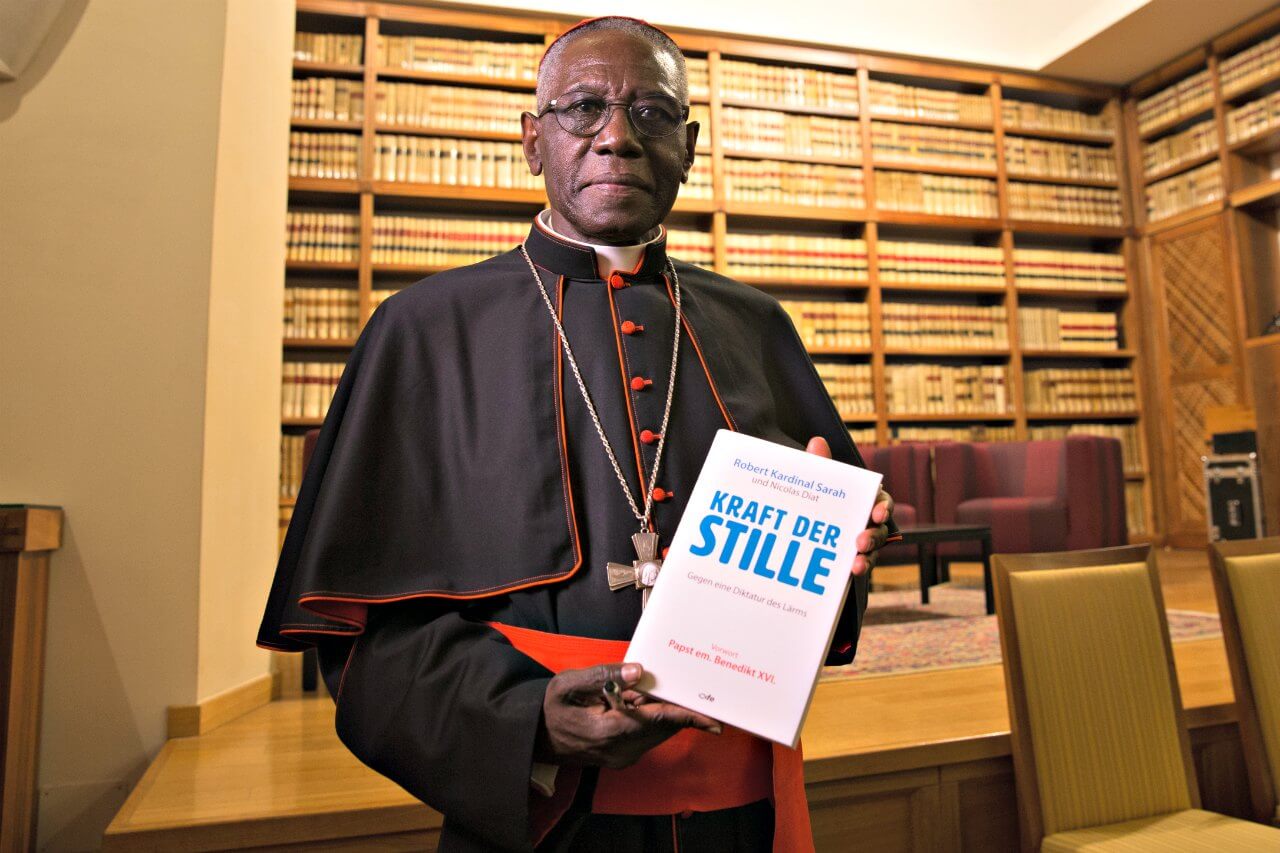

Image courtesy of Daniel Ibáñez EWTN

On 24 May, the German edition of Cardinal Robert Sarah’s new book, The Power of Silence – Against the Dictatorship of Noise, was presented in Rome, with Cardinal Sarah himself being present. (Edward Pentin, who attended the presentation, has an interview with Sarah here.) This German edition had caused much media attention even before its official launch because Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI had written, on his own initiative, a foreword for the book in which he especially praised Cardinal Sarah as the Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, saying: “With Cardinal Sarah, a master of silence and of interior prayer, the liturgy is in good hands.”

At the event, Bernhard Müller, the founder of the German publishing house, Fe-Medienverlag, which published the German edition of the Sarah book, expressed his gratitude for this surprising initiative by Benedict XVI. He also related some stunning events in his own life that are, providentially, related to the publication of this new Sarah book – events which had to do with protracted suffering and the many graces received during this lengthy trial. (Archbishop Georg Gänswein was also among the speakers at the book presentation. At the end of his own speech, he read out loud Pope Benedict XVI’s foreword to the book.)

But before we say more about Müller’s touching comments, let us first consider the words of Cardinal Sarah himself, as spoken during the 24 May book presentation at the Church Santa Maria dell’Anima, which is also the seat of the German-speaking parish in Rome as well as of a college for German-speaking priests.

Cardinal Sarah explains that this new book of his “has grown out of life.” The book is a fitting fruit of his “personal experience and the experience of people who are dear to me, and whom I was able to meet and who have been able bring forth rich fruits in silence and through their silence.” In the following, Cardinal Sarah presents us with two examples that were influential for this book. Both instances are related to well-borne suffering and how such suffering can bring forth much strength and other good fruits.

The African cardinal first speaks about Brother Vincent-Marie de la Résurrection, a Canon of the Abbey Sainte Marie di Lagrasse whom he met in 2014. Cardinal Sarah explains:

He suffered under Multiple Sclerosis which caused him to die in 2016 at the age of 37. Brother Vincent could not speak. But between us, there grew a beautifully spiritual relationship – not with the help of words, but through looks, through silence, and through prayers in which Brother Vincent only participated by moving his lips.

This piercing encounter with such suffering and attendant spiritual beauty has deeply influenced Cardinal Sarah, as he adds:

Brother Vincent was able to open up for me in a very special way this human and mystical dimension of silence. I can thus say that the book which is being presented here today has been born in the chamber of a sick man, of a young monk who was awaiting Heaven in a body which bore more and more the signs of suffering but which also – as I would like to say – was radiant, because through it shone already the Light of the Resurrection.

In the following, Cardinal Sarah speaks about his own personal suffering during and under the dictatorship of Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea, Africa:

For me, silence is, however, also part of a personal experience of the first years of my episcopal service in Conakry in Guinea, where I lived in a very isolated and controlled way – under those well-known political conditions which I have already described in my first book [God or Nothing – see here Cardinal Gerhard Müller’s words at that books’ presentation in Germany]. The external isolation opened up for me at the time – as a great gift from God – those inner realms, foremost, into which God enters and and in which He dwells and speaks and consoles.

It is just these kinds of experiences, explains Cardinal Sarah, that help us still today “to reach a deeper discernment as to what surrounds us – in a cultural environment which nearly systematically avoids being alone with oneself and looking inside oneself.” He continues: “The noise, the chatter, and the new technologies which transport this noise cover up the emptiness of a new man who barely knows anymore for what purpose he shall live.”

This noise and distraction, according to Cardinal Sarah, has also now entered the Catholic Church itself:

Even more painful is for me, however, to notice how this superficiality and godlessness and disdain of the human person have in the meantime entered the Church. I cannot deny, therefore, that this book is also based on my experiences as the Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Because I must say that the liturgy is that dimension in the life of the Church which might suffer the most under this degrading secularization which has also entered the Church.

In explaining these words, Sarah points to the fact that our modern world lives “as if God does not exist.” There is an “emptiness” in man which “stems from the absence of God.” However, in searching for an “access to the absolute,” says Sarah, man realizes that “nothing that is merely human can completely fill his heart.” Importantly, Cardinal Sarah adds: “But it is problematic that we seek merely human solutions as an answer for our [own quest for our] destination.” In the face of great problems, explains the cardinal, “we insist upon human means instead of lifting up our hearts to God.” [emphasis added] The African cardinal then presents a striking thought: “Sometimes I have the impression that this secularization has entered the Church in order also to reduce our Faith to a human standard.” [emphasis added] A “Faith according to human terms” is being presented to man “which is not any more rooted in the depth of the Revelation of Christ and the Tradition of the Church, but, rather, in the claims and [purported] needs of modern man.” For Cardinal Sarah, “this secularization can also be seen in the liturgy.” In the liturgy of today, one can see “a reduction of the Faith according to merely human standards and human whims in all of its weight, be it in the words or the gestures.”

It is in this context that Cardinal Sarah laments that in our homilies nowadays, there is barely talk anymore “about the Faith, eternal life, the communion with the Person of Christ, sin as a breach and a rebellion against God.” He goes on:

And are there not attempts being made, also to extinguish all those gestures which seem “incomprehensible” to modernity, in order to replace them with a gush of words which turn our Eucharistic feasts more and more into great happenings at whose center stands man, enclosed in himself with his problems and with his own judgment to solve these problems? Is this, however, not rather only anymore a human feast – rather than a true worship of God and a feast of the Church?

It is to be hoped that many clergymen in the Church would now attentively listen to Cardinal Sarah here. One can clearly see how, in his case – as well as in the case we shall discuss in a short while – suffering has led to great depth of heart and soul, to a persevering strength that is much needed in our time of great tests and challenges. (In this context, Bishop Athanasius Schneider also comes to mind whose grace-filled Catholic witness seems to have been formed by living under Soviet Communism.)

Let us now return to Bernhard Müller who, as the publisher of the German edition of Sarah’s book, has his own special story to tell. This story is beautiful, because, as it turns out, Müller himself, as a young man, was deeply engaged in helping an African archbishop – Raymond Tchidimbo – to be freed from prison under that same dictator, Sékou Touré, who later caused Cardinal Sarah’s own suffering. And, as it turns out, Cardinal Sarah has even dedicated his new book to that same devout prelate, his own predecessor in Conakry, Guinea!

Archbishop Tchidimbo – who was imprisoned and tortured for eight years – had heard about the young man (Bernhard Müller ) and his own little group’s initiative in defense of him – and later, after his liberation in 1979, he personally contacted them in order to thank them. The African archbishop went to Germany and even visited Bernhard Müller, his brother and another friend and their parish for a week and sang to them the songs he had written (but never sang) during his own imprisonment – without ever being able to sing them aloud, out of fear for his life. As Müller puts it:

We experienced days of grace-filled encounters with Archbishop Tchidimbo. It was a week which formed us for our future life. Many sentences which he said to us then, we never forgot: “If one has been for so long in prison, everything is of much value – also the little things.” And: “Only he who once has been in prison can assess the value of freedom.” […] A man who had suffered so much for Christ impressed us. He became a strong motivator for our further work [called Fatima-Aktion, inspired by the message of Fatima].

The German publisher concludes this beautiful story by saying:

Today, nearly forty years after our first meeting with Tchidimbo, our Fe-Medienverlag – which came out of the Fatima-Aktion and belongs to it – now publishes a book of his successor, Cardinal Robert Sarah, with the title The Power of Silence. […] Cardinal Sarah writes on page 127 [of his new book] that Tchidimbo knew “that his prison was like a field; daily he sowed there [the seeds of] his life – just as one sows a kernel of wheat – fully aware that those who sow in tears will harvest in jubilation.”

Such is the message of these brave men from Africa. May it give us all a greater genuine hope that our own suffering and toil in this world may bring good fruit at some later point – even if we are not blessed to see it right away, or even not at all in this life.