Above: Lincoln cathedral viewed from the castle.

Even on his deathbed, Saint Hugh of Lincoln had plenty of verve. An Archbishop whom Hugh had thwarted visited the dying saint. Hugh told the prelate, “I am well aware that I have often annoyed you. But my sole regret is that I did not oppose you more often and, if God should spare my life, I am resolved to take a firmer line towards you. I have too often offended God, because I shrank from offending you.”

As a cleric, monk, prior, and eventually bishop, Saint Hugh of Lincoln (whose feast is November 17th) showed an extraordinary care for souls, whether it was the King, his fellow bishops, monks, or lepers. Famous for his pursuit of church reform and political justice, Hugh is a good example of the fact that “pastoral” leadership is not always gentle or compromising.

Born in 1140 to the noble family of the Lords of Burgundy, Hugh was the youngest of three brothers. At the age of eight, Hugh’s mother died and he and his elderly father entered a community of Augustinian Canons. The Prior put Hugh in charge of his father as his health failed. A few years after being ordained a deacon, he was put in charge of a parish. However, like Blessed Columba Marmion, he desired a contemplative life rather than the position of a parish priest. In his early twenties, Hugh visited the Grande Chartreuse and became enamored of the Carthusians. His medieval biographer beautifully describes the monastic ideal:

Their rule encouraged solitude, not isolation. They had separate cells but their hearts were united. Each of them lived apart, but had nothing of his own, and did not live for himself. They combined solitude with community life. They lived alone lest any should find his fellows an obstacle to him; they lived as a community so that none of them should be deprived of brotherly help.

Hugh’s Augustinian Prior found him so helpful however, that when he saw Hugh eager to become a Carthusian, he made Hugh take a vow not to enter until the Prior had died. Hugh complied under pressure but finally decided that it was a rash vow, and against God’s will. At the age of twenty-three he entered the Carthusian order.

He related that his life in the cell alternated between extreme consolation and dryness so that at times “weary and fainting” he tasted “from time to time that hidden mana,” gaining strength to “lightly despise whatever the world knows of sweet or bitter, smooth or rough” before being “flung back into the fray.”

An amusing story is told of his desire for ordination. An old monk Hugh was tending wanted to test him, telling him that an ordination was approaching. Hugh replied, “So far as I am concerned, Father, there is nothing in the world I would like better.” The old monk pretended to be shocked: “What have you said? Oh, what have you said? Who would have expected such presumption? How often have you read that he who does not receive the priesthood unwillingly receives it unworthily! You, however, are eager for it.” Hugh begged pardon for his “presumption,” but the elder replied, “I know with what sentiments you spoke as you did… You will very soon be a priest and later in God’s good time a bishop.” Though clothed in stylized hagiographical language, I can nonetheless imagine a curmudgeonly old brother and the idealistic and eager young Hugh genuinely having such an exchange.

Once ordained, Hugh showed great reverence and eagerness in celebrating the Mass. One biographer said that his devotion “to the mystery of the altar was life-long, and he could have said from one moment to another: ‘I am preparing to offer the Holy Sacrifice;’ or ‘I am still making my thanksgiving.’”

In 1180 Hugh was sent to England to become prior of a new charterhouse at Witham. This foundation was part of the King’s penance for murdering Thomas Becket. The project had been badly mismanaged and this young monk from France was seen as ideal for getting it on good footing.

When Hugh arrived, his first task was to properly transfer the serfs and peasants who were living on the land without making them lose money or property in the process. Henry delayed giving the funds needed, and Hugh finally threatened to return to France. After this confrontation, despite recurrent quarrels and tensions, Henry and Hugh loved and respected each other.

Six years later, a council was held to elect a bishop for the see of Lincoln. This see had been vacant for eighteen years while the King enjoyed its revenues. After being consecrated bishop, Hugh regularly returned to Witham for “monastic vacations” from his episcopacy, during which time he lived like a simple monk, save for his episcopal ring.

Hugh’s first act in resisting corruption was to refuse to pay the Archdeacon the customary fee for his episcopal enthronement because he regarded it as simony. Hugh was devoted to the solemn celebration of the liturgy. Once, when he was assisting at Mass with the bishop of Coventry before dining with the King, the bishop began a spoken Mass so as not to delay dinner. When he began speaking the Introit, Hugh, who sang his daily Mass, intoned the Chant with all the notes! On a similar occasion, Hugh said to his clergy, “It is better to let an earthly king dine without us, than to pay no heed to the invitation of the King of Kings.”

Tales of episcopal laxity in England at the time say that bishops sometimes administered Confirmation out of doors without even getting off their horses! Hugh, however, ensured the Sacrament was performed with reverence. We are told of one yokel who would not go to a church but demanded to be confirmed on the spot, and Hugh agreed. However, when the time came for the ceremonial slap of the cheek, Hugh taught the peasant a lesson.

Hugh demolished several improper shrines, including that of the mistress of King Henry, “fair Rosamund,” who had been buried splendidly in the choir of the nuns of Godstow. As a medieval bishop, Hugh also filled roles later held by judges and state officials. Hugh did not shrink from excommunicating people for various offenses, and some died soon after the sentence was given them. Unsurprisingly, this made the Bishop of Lincoln immensely respected.

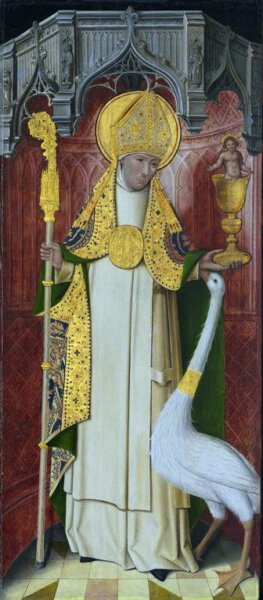

Hugh is frequently depicted with a swan, which lived in his episcopal manner. The swan recognized Hugh even after an absence of two years, and would happily bury its head in Hugh’s sleeves, or eat bread from his hand. Artistic depictions also sometimes show a Eucharistic miracle Hugh experienced when the Christ Child was made visible as he held the host over the chalice.

Hugh’s last major struggle was with King Richard in the last years of the 12th century. The King demanded from both bishops and lay barons troops and financial support. The bishops at the December 1197 council were going to consent, calling to mind (E. I. Watkin says) the medieval adage Episocpi semper pravidi: “bishops are always timid.” Hugh refused though, and changed the mind of the Bishop of Salsbury. This lead to the dissolution of the meeting without the king’s wishes being fulfilled. Negotiations continued, and Hugh traveled to France where Richard was fighting several times.

On the final return trip to England, Hugh’s horses and baggage were stolen. Nonetheless, he celebrated a Pontifical Mass, and found the stolen property returned when he left the church. In 1199 Hugh’s health began to fail and shortly after returning to England he became bedridden. He had the Divine Office said with reverence in his room and received Communion frequently.

In his suffering Hugh would cry out, “Merciful Savior, give me rest,” and “Blessed are those whom the Day of Judgment will introduce into endless rest.” Hugh died lying on a cross of ashes as his brethren begun singing the Nunc Demitis during compline. He was canonized by Pope Honorius III in 1220, the earliest canonized Carthusian.

Hugh is one of those tremendously alive medieval personalities, whose strength and sparkle shine through to us despite the intervening centuries. He reminds us to oppose men more—both Kings and Bishops—so that we might oppose God less. Another lesson he teaches is the prioritization of worship over temporal concerns, and the strength secular clergy can draw from the wells of monastic spirituality. A hard slap, sung Pontifical Mass, or a monastic retreat would do all of us good, bishops included. Saint Hugh, pray for us!

This is a rewritten and condensed version of an article that appeared in the March 2018 edition of Latin Mass Magazine. My information is sourced from: E. I. Watkin, Neglected Saints, (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1955) and Herbert Thurston, S.J., The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln, (London: Burns & Oates Ltd., 1898). The first quotation is from A Carthusian Monk, Carthusian Saints (Charterhouse of the Transfiguration, 2006).