Do you worry about today or what the future holds? Opening the newspaper or reading the latest tweet certainly provides enough kindling for worry to become a roaring fire. If this sounds familiar, you are not alone.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about fears Americans and other nationalities confronted in the past. Pondering history is not meant to diminish current events that cause anxiety, especially this past year. However, stepping back to consider other difficulties in America’s history can provide encouragement (we’ve been here before) and hope (we’ve also moved on before).

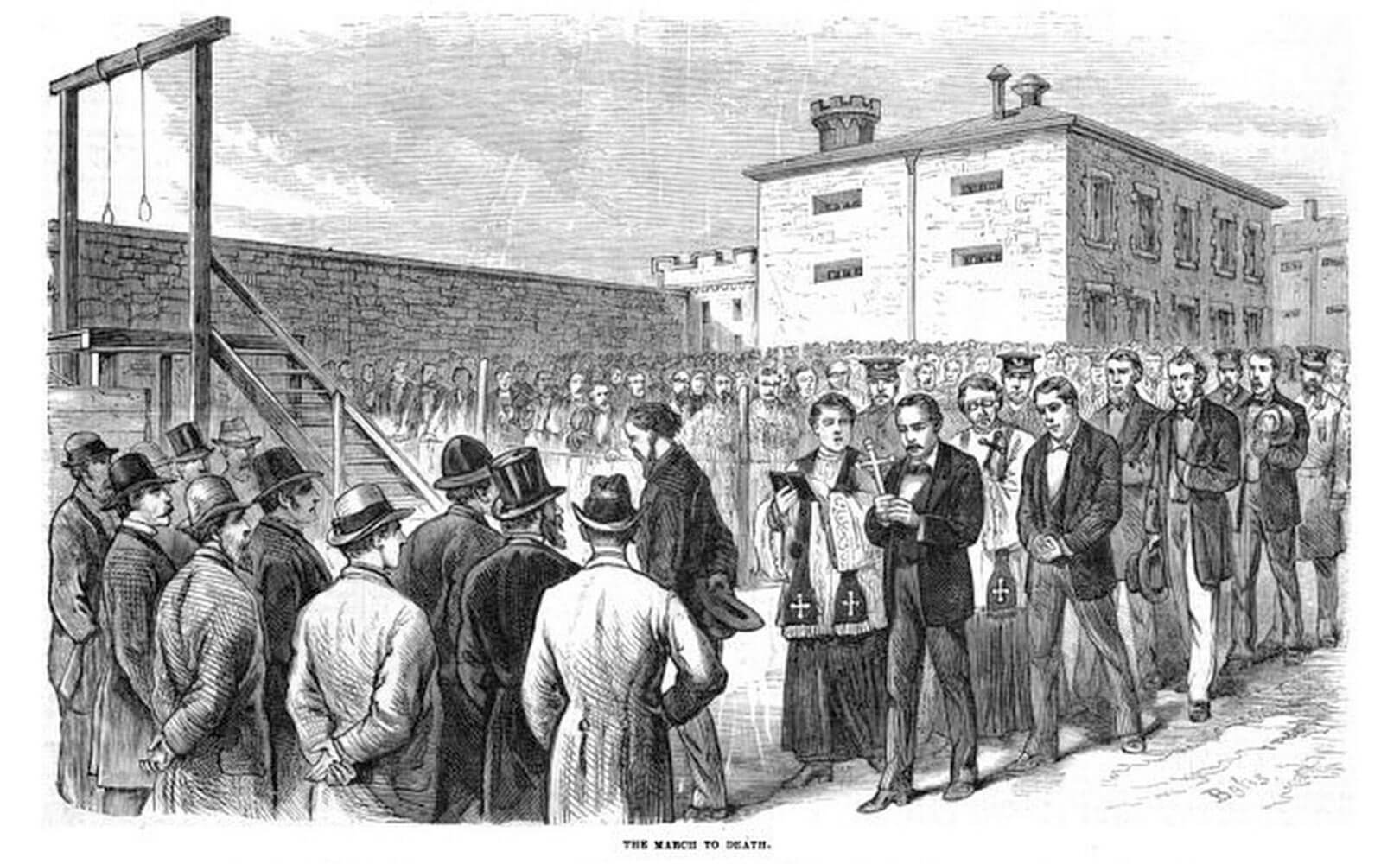

Most folks have no particular reason to remember June 21st. But in 1877, it became known as Black Thursday, or the Day of the Rope, when Pennsylvania hanged 10 Irish Americans. Within 18 months, the state hanged 10 more. If you’re not familiar with the story, ask someone from the anthracite coal region of northeastern Pennsylvania to tell you about the Molly Maguires, or watch the Sean Connery movie about it. My husband told me about his great-grandfather, a member of the group.

Irish Catholics fled atrocities, starvation, and the Great Potato Famine. They did not arrive in America as a privileged group but clawed their way to a better life through hard work and determination. They readily accepted the sacrifice, for in exchange, America offered them “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Like other immigrants, they started at the bottom of the economic scale working in the coal mines. Miners earned $3 a day working 12-hour shifts 6 days a week; mine owners took rent from wages. With no choice but to shop and pay inflated prices at the company store, they fell deeper into debt with the mine owner. Breaker boys entered the coal mines around age 9.

Coal miners experienced dangerous working conditions, including hazardous gases, coal dust, smoke, falling rocks, fires, and flooding. If they survived the coal mines, many succumbed to fatal pulmonary diseases by age 50. My husband’s maternal grandmother lost two husbands to coal mining accidents.

Enter the Molly Maguires, a labor movement that pushed for fair wages and safer working conditions. Mine owners had no sympathy. Frank Gowen, who headed the Reading Railroad, and the monopoly on railroad and coal mining, was determined to end the Mollies. With unlimited resources and political power, he used extreme measures, creating his own Coal & Iron Police and hiring a Pinkerton Detective to infiltrate the group.

After the collapse of a strike for better conditions, miners’ wages decreased 20%. The region began experiencing tit-for-tat violence between railroad/mining bosses and Molly Maguires. Gowen’s Coal & Iron Police and the Pinkerton informant shockingly escalated tensions by shooting Mollies, including the killing of a pregnant mother and her unborn baby. The perpetrators were not arrested, although witnesses saw Gowen’s Coal & Iron Police at the scene.

The exact actions of the Molly Maguires remain unclear. Debate raged whether Mollies or vigilantes killed mining and railroad managers. The Molly Maguires contended they were victims of false evidence. Historians now believe the Pinkerton informant, whose testimony condemned all 20 men, provided false statements.

Gowen’s lethal and political power had no bounds. He even convinced Archbishop James Wood to threaten Molly Maguires with excommunication. The Mollies ignored the Archbishop.

Intent on halting the group’s push for labor rights, Gowen also led efforts to mastermind kangaroo trials — all to rig the outcome. They prohibited Irish Catholics from serving as jurors and instead used jurors lacking English or from immigrant groups with prejudices against the Irish. Harold Aurand, in “Coal Cracker Culture,” wrote about the miscarriage of justice:

“The Molly Maguire investigation and trials marked one of the most astounding surrenders of sovereignty in American history. A private corporation initiated the investigation through a private detective agency, a private police force arrested the supposed offenders, and coal company attorneys prosecuted — the state provided only the courtroom and hangman.”

Not surprisingly, jurors returned guilty verdicts. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hanged 10 Mollies on 21 June and another 10 during the ensuing months. Instead of standing up against the wickedness, officials stood by as private citizens bent the levers of government for illegal goals — they got away with it for 102 years.

This changed in 1979, when Pennsylvania pardoned the group’s leader, who had been hanged along with the others, and admitted the trials and hangings represented “a shameful part of…history.” The Schuylkill County Historical Society now highlights the Molly Maguires and sells a book describing them as “labor’s martyred pioneers.”

A few days before his hanging, Patrick Hester spoke about the injustice. While declaring his innocence, he prayed for God to forgive the men who had illegally plotted against him. Remarkably, he acknowledged “everything has to come as God wills it.” Other Molly Maguires did the same. An article summed up the men with one word: fortitude.

My husband’s great-grandfather, Patrick Collins, also had fortitude. Holding a position in the group made Collins a marked man. An 1878 New York Times hit-piece on him praised the “Honorable” Gowen, who smugly asserted, “the day will come” when he “[will] be hung” in the very “jail” Collins built as County Commissioner. Collins lived into old age; Gowen didn’t.

We credit Patrick’s survival to God’s providential mercy. From knowing Mollies that hanged to being falsely accused, he endured “evil men” conspiring to “make this evil world” (St. Augustine). He could have become embittered toward life, America, and God. But, he did not.

Patrick taught his children to love God and country and to stand up against wrongs; these values continued like a river flowing through his descendants. Each generation has shown faithful fortitude and served America, either in the military, fighting to protect our freedoms, or on the Homefront. This happens not by accident, for “one generation commends” Godly faith and values “to another” (Psalms).

That mantle now passes to us. Ours is a duty to teach the next generation to love God and country and to stand up against wrongs. Let challenges not overwhelm — ponder history, and perhaps today’s troubles will pale in comparison. With Father’s Day just yesterday, it’s appropriate to remember “my father’s God” is also “my God,” and He is most certainly “my strength,” “my defense,” and “my salvation.”