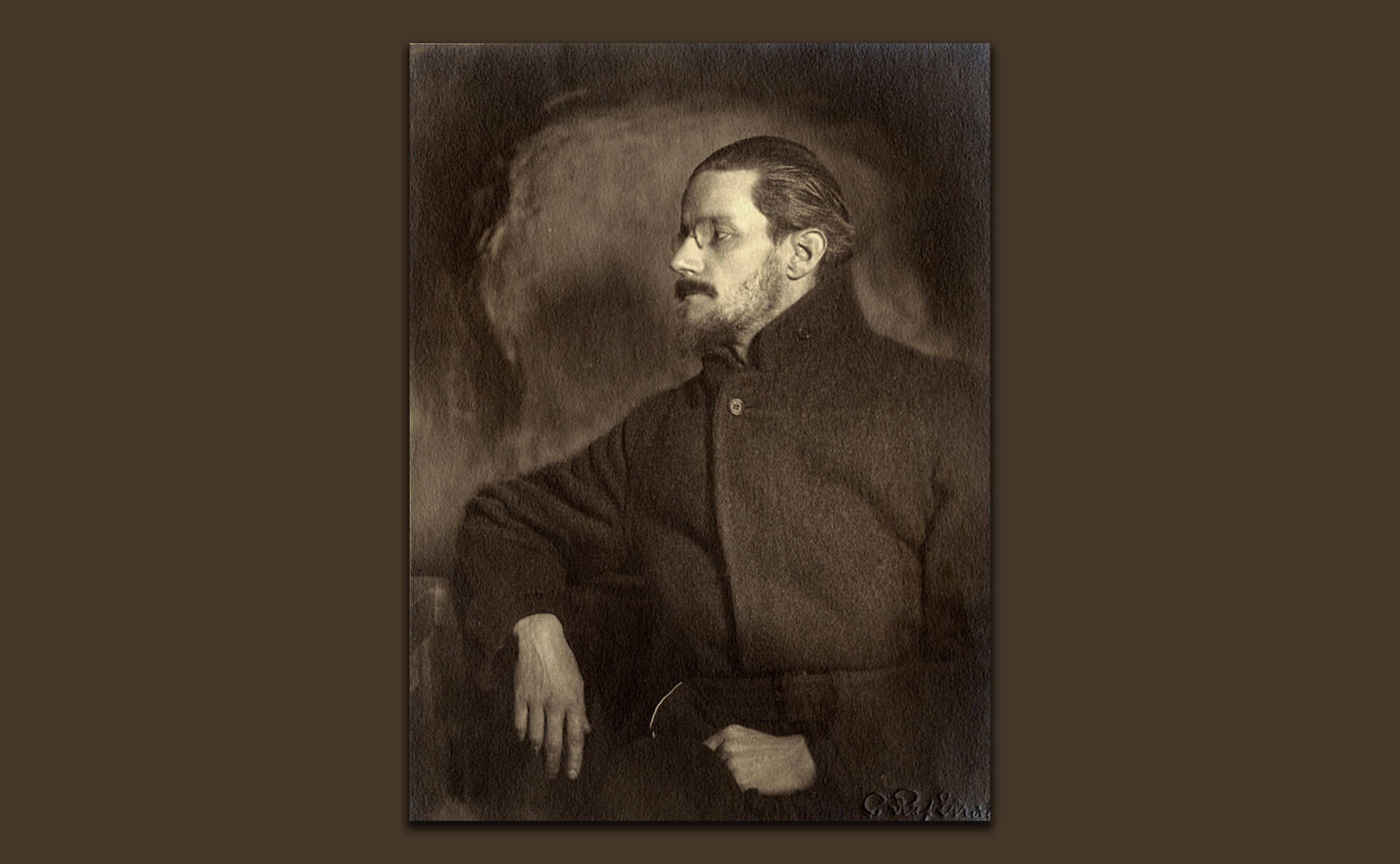

Eighty years ago this week, on January 12, 1941, James Joyce (Dublin 1882 — Zurich 1941), a great wordsmith, an Irish writer counted among the greatest of the twentieth century, fell into a coma following an operation for an ulcer performed the previous day. On January 13th, he died. He was less than a month from his 59th birthday.

After studying with the Jesuits of Dublin (Clongowes Wood College, Belvedere College and University College), Joyce established a love-hate relationship with Ireland, the Catholic Church and the sons of St Ignatius of Loyola. He left Dublin to live in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris, but made his hometown the setting of all his literary work, from his early youth essays to the most famous novels such as Ulysses (1922) and Finnegan’s Wake (1939). Revealing a masterful command of English language and literary technique, Joyce complained that he had no imagination but only memory, and his interest was not in content, but in style.

“Joyce has a most g***damn wonderful book,” Ernest Hemingway said of Ulysses (R. Ellmann, James Joyce, Oxford University Press, New York 1982, p. 531). It was a book written by someone who had once planned to become a professional tenor. Joyce wrote to his younger brother Stanislaus on June 11, 1905: “Sinico, a maestro here, tells me that after two years I can do so. My voice is extremely high: he says it has a very beautiful timbre.” (Letters of James Joyce, Vol. 2, Viking Press, New York 1966, p. 91). But, due to his impatience and the failure to pay his fees, his lessons with Francesco Riccardo Sinico (1869-1949), the most famous singing teacher of Trieste, were interrupted.

His passion for singing and his vast musical erudition must have taught Joyce to convey on the page that ability to hear music in the head, known among musicians as the “inner ear,” going beyond the objective sense of words. In Ulysses there are indeed many musical references: “from opera to obscene nursery rhyme, from a Gregorian chant (Gloria in excelsis Deo) to the viceroy’s cab noise passing along the waterfront (“Clapclap, Crilclap”), from nursery rhymes to a German poem about the sirens’ song (Von der Sirenen Listigkeit…), from verse cuckoo (“Cuckoo! Cuckoo”) to Flower of Seville (opera), from jokes to keep the rhythm of a page (“Tum” “Tum”) to those of other sounds (“Pflaap! Pflaap! Pflaaaap”), to the Mozart cantata, recurring in the thoughts of Mr Bloom: Vorrei e non vorrei, mi trema un poco il cor [I should like to, yet I shouldn’t, my heart trembles a little], and so on” (G. Celati, Foreword to Ulysses, Einaudi, 2013, p. IX).

In particular, the young destitute writer Stephen Dedalus, protagonist of the first part of Joyce’s novel, mentions the Credo from the Missa Papæ Marcelli by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (Palestrina 1525 – Rome 1594). Brilliant maestro, he is “the real prince of sacred music, and the Eternal Father of Italian music”, in the words of Giuseppe Verdi (Letter to Giuseppe Gallignani of November 15, 1891, in I copialettere di Giuseppe Verdi, Milano 1913, p. 373); “classical polyphony”, as St. Pius X would so well say, “reached its greatest perfection in the Roman School precisely owing to the works of Pierluigi da Palestrina (cfr. Pius X, Tra le sollecitudini, November 22, 1903, n. 4).

Written around 1562 in the spirit of the Catholic Reform promoted by the Tridentine Council (1545-1563), named in honor of Pope Marcellus II (on the papal throne for only three weeks) and dedicated to Philip II, King of Spain, the Missa Papæ Marcelli is conceived for mostly six voices (soprano, alto, two tenors and bass). It became the most famous Mass by the great composer since the early seventeenth century and was performed at every coronation of the Roman Pontiffs up to John XXIII (1958). Dedalus considers it from two points of view: the musical aspect (“the voices blended, singing alone loud in affirmation”) and the religious one (“and behind their chant the vigilant angel of the church militant disarmed and menaced her heresiarchs”). Thanks to his literary sensitivity, Joyce’s alter ego (Dedalus) sees in Palestrina’s mind two tensions: that between imitated and homophonic style and that between orthodoxy and heresy.

The opening phrase of the Kyrie, in imitated style, “is like a benediction, quietening the spirit with a heavenly sense of peace; or it suggests a vision of the white wings of a dove folding as they come to earth” (Z. Kendrick Pyne, Palestrina: his life and time, Londra 1922, p. 56); the Christe is homophonic at the beginning and the final Kyrie is again in imitated style. The Gloria is almost entirely homophonic, as is the Credo, which in the Crucifixus decreases the number of voices to four and returns to six voices before the Et in Spiritum Sanctum. But it is in the melismatic (multiple notes sung to one syllable of text) Sanctus “that Pierluigi reaches that fullness of sound, that suave harmony transfiguring the words as a nimbus adorns the pure, pale face of a saint” (Z. Kendrick Pyne, ibidem p. 57). The Benedictus is for four voices and the two Agnus Dei are elaborated in a complete polyphonic plot, with a canon in the second one.

The first Dublin performance of this score was at St. Teresa’s Church in 1898: it seems that Joyce took part in it and that he felt almost a correspondence of intentions. While the author of Ulysses wants to make Homer’s epic and Shakespeare’s tragedy contemporary, that of the Missa wants to link tradition and innovation to obtain church music free of any “impurity” (complicated, sumptuous music, with secular motifs adapted to liturgical texts, now rendered incomprehensible by the numerous overlapping melodies and by too many ornaments).

Those saddened in church music by the mediocrity, superficiality and banality, which sometimes prevails, to the detriment of the beauty and intensity of liturgical celebrations, might find some consolation with Joyce in “some of that old sacred music [which] is splendid. Mercadante: seven last words. Mozart’s twelfth mass: the Gloria in that. Those old popes were keen on music, on art and statues and pictures of all kinds. Palestrina for example too.” (J. Joyce, Ulysses, Alfred A. Knopf, 1997, p. 122).