Growing up in the Novus Ordo, I was never accustomed to using a missal, nor did I ever see anyone else using one. Preacher said we had to take up our hymnal and follow it, but it was a rare bird who followed the Mass from a missalette. The vernacular was supposed to make everything accessible, and the texts themselves were simplified, so missals lost much of their point.

When I discovered the traditional Latin Mass in college, part of the huge draw of it to me was precisely the daily missal — that monumental resource of rich prayer and meditation. I looked forward to taking up this book whenever I could get to Mass, setting the colorful ribbons in it ahead of the bell, and following the golden path of the liturgy from start to finish.

Then I discovered what most traditional Catholics discover before too long: how to pray with the Missal outside the church. Say you get sick and have to stay in bed, maybe for several days, or your car battery turns out to be dead, or the only TLM-equipped priest in your area is away on retreat, or, for whatever other reason, getting to Mass is impossible. You pick up your Baronius or St. Andrew’s or Lasance missal, open to the Introit, and start quietly speaking the words. You bow your head at the Gloria Patri and repeat the Introit, then say Kyrie eleison three times, Christe eleison three times, Kyrie eleison three times. The Collect follows. And so, through the Epistle, Gradual, Tract or Alleluia, Gospel, etc., until the end.

At first, you don’t have much of a clue how to go about doing it. What text do I say, and when? Should I pray certain things or skip them? No matter how smooth or bumpy the initial trials, you come to the beautiful realization that yes, indeed, I can do a layman’s “dry Mass” on my own, so that I am uniting myself spiritually with the Church’s greatest prayer wherever it is being offered in the world.

The coronavirus epidemic has laid bare many implicit assumptions of our time. With Masses discontinued almost everywhere, look at the advice being given to the laity by pastors and popular writers: “Read the Scripture readings of the day” and/or “Make a spiritual communion.” These are obviously good things to do, and we should do them. But note that either of these things could just as easily be said by and to a Protestant: read your Bible and wish to be united to Jesus, the Bread of Life. (Indeed, this is more or less how Protestants interpret John 6.) I would submit that, as well intentioned as such advice is, it misses the forest for the trees.

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is first and foremost the offering of the Holy Victim to God, to which the readings and prayers lead up, as if one were climbing a winding path to the summit of the mountain. Sacramental communion is then available for those who are duly prepared to join themselves to the High Priest and Victim in the most intimate manner possible. Current advice to Catholics suggests that, in the minds of many (as in the minds of many liturgical reformers), the Mass has been redefined — or rather, reduced — to a gathering for Bible-reading and Communion.

Prayerfully reciting the antiphons, orations, and readings in a traditional missal; pausing after the Secret to offer up to the Father the all-pleasing Host at the hands of priests around the world who are saying Mass that day or at that moment; and, at last, making a spiritual communion: this is a more Catholic way to join oneself to the great sacrifice that pleases God. People may even find it more spiritually fruitful than watching a televised Mass, which can have something artificial about it and is, in any case, not at all different existentially from doing devotions on one’s own. (In other words, the televised Mass may help you to pray, but the Real Presence is over there in the chapel being filmed, not right here in your room; you would be doing essentially the same thing by imagining yourself present at Mass a few blocks away when you hear the church bells ringing.)

What follows are two methods for using a TLM missal for personal prayer: a Shorter Method (which takes about 15 minutes) and a Longer Method (20–30 minutes), with the length of time varying depending on how long the readings are, if there are extra commemorations, and how much you choose to meditate on the texts or keep periods of silence. The PDFs are formatted as booklets: print them double-sided and fold (for best results, select “None” for “Page scaling” rather than “Fit to printable area”). Either method may be done in English, in Latin, or in whatever proportion of either you are comfortable with. Postures are your call, even as they are in the Latin Mass itself, which has no regulations governing the postures of the faithful. You could, for example, kneel for the Kyrie and the orations, while sitting for the Epistle and standing for the Gospel. Or sit for the whole.

Praying the TLM (Longer Method)

Praying the TLM (Shorter Method)

Praying the TLM (Longer Method, Laetare Sunday)

Praying the TLM (Shorter Method, Laetare Sunday)

(The first two links lead to general templates that can be followed any day of the liturgical year. To show how the Propers of the Mass fit into the structure, I have also provided fully realized booklets for the Fourth Sunday of Lent; nothing else is required than the booklet.)

Either method may be adapted for communal use in a family on Sundays (or on any day, especially for feasts of favorite saints like St. Joseph or Our Lady). The father of the family, if possible, otherwise the mother, should read the texts out loud from the missal, and the others present could make the responses.

On days in my life when I could not make it to Mass, I have never found anything more edifying as a form of private prayer than to “pray” the Mass in this way.[i] It may look complicated, but it’s rather straightforward in practice, and it quickly becomes second nature. If one finds the right time of day to do it (usually first thing in the morning), it will help us to follow the Apostle’s advice: “Be not conformed to this world; but be reformed in the newness of your mind, that you may prove what is the good and the acceptable and the perfect will of God” (Rom. 12:12), and “let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 2:5). The traditional lex orandi delivers to us and inculcates in us this supernatural wisdom, and we do well to remain close to it.

[ADDENDUM: Apparently the three hyperlinks given at the top of the PDFs do not work. Here they are: (1) for those who do not own a daily missal, Maternal Heart of Mary in Sydney has provided all the Propers of the Mass for Sundays and feastdays; (2) those who would like to read a Sunday homily from the Church Fathers, keyed to the traditional calendar, here’s the book for you; (3) those who are interested in finding out more about practicing lectio divina with the traditional missal may find this series at New Liturgical Movement helpful: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.]

[CORRIGENDA: (1) In three of the booklets, the last of the suggested prayers for making a Spiritual Communion says towards the end: “The love embrace my whole being in life and in death.” This, of course, should be: “Thy love…” (as in: “May Thy love…”). (2) In the Laetare longer booklet, the Gloria was inadvertently included. I have uploaded a correct file.]

[i] Naturally, I would not say it is equivalent either to praying the Divine Office, which is the liturgy in a way that meditating on a missal isn’t, or to praying the rosary, which Our Lady specifically requested from us. But some people can do all of these things, and others will have one or another reason to prefer this or that one. The Church leaves us free.

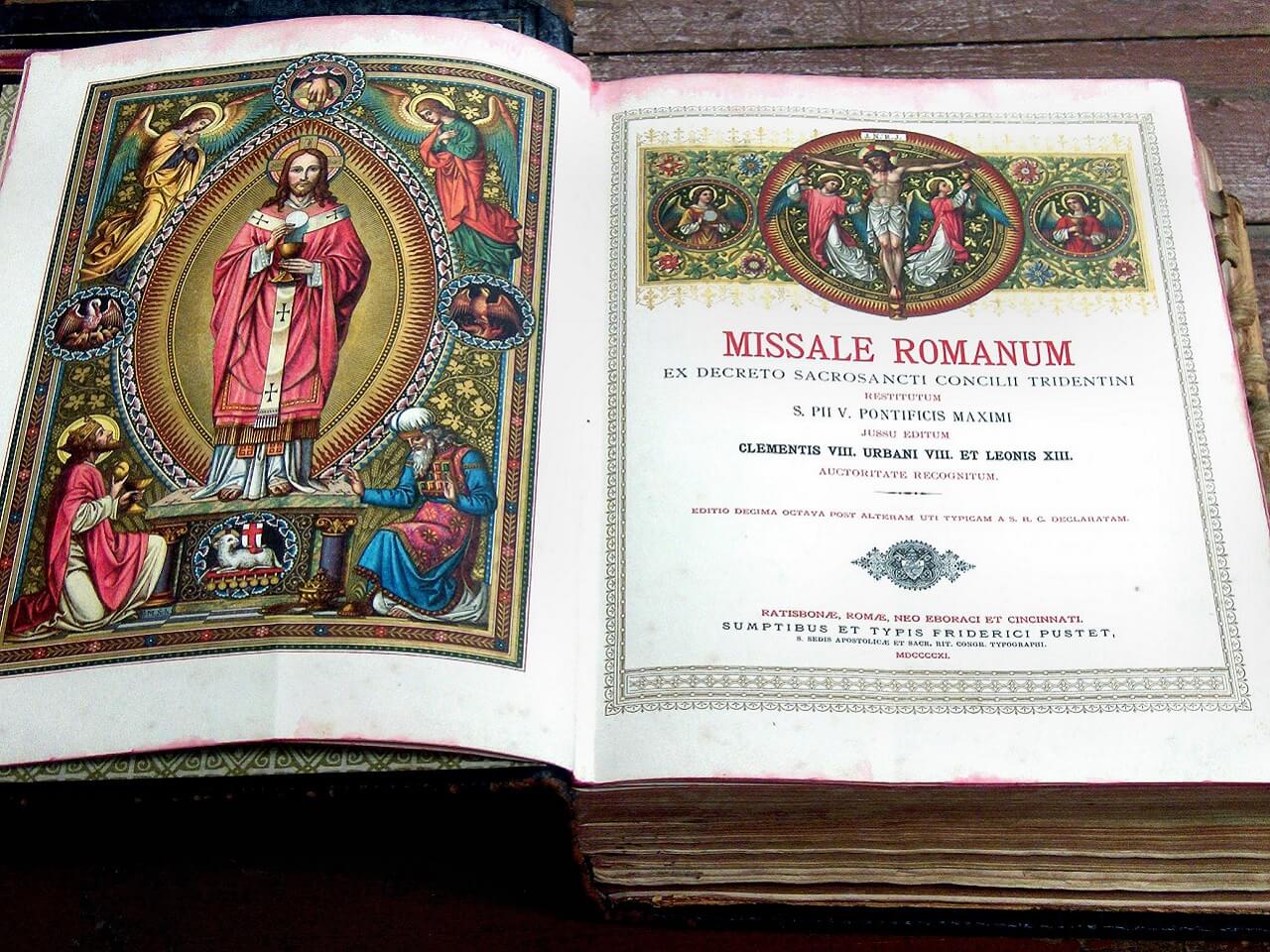

Image: JoJans via Wikimedia Commons.