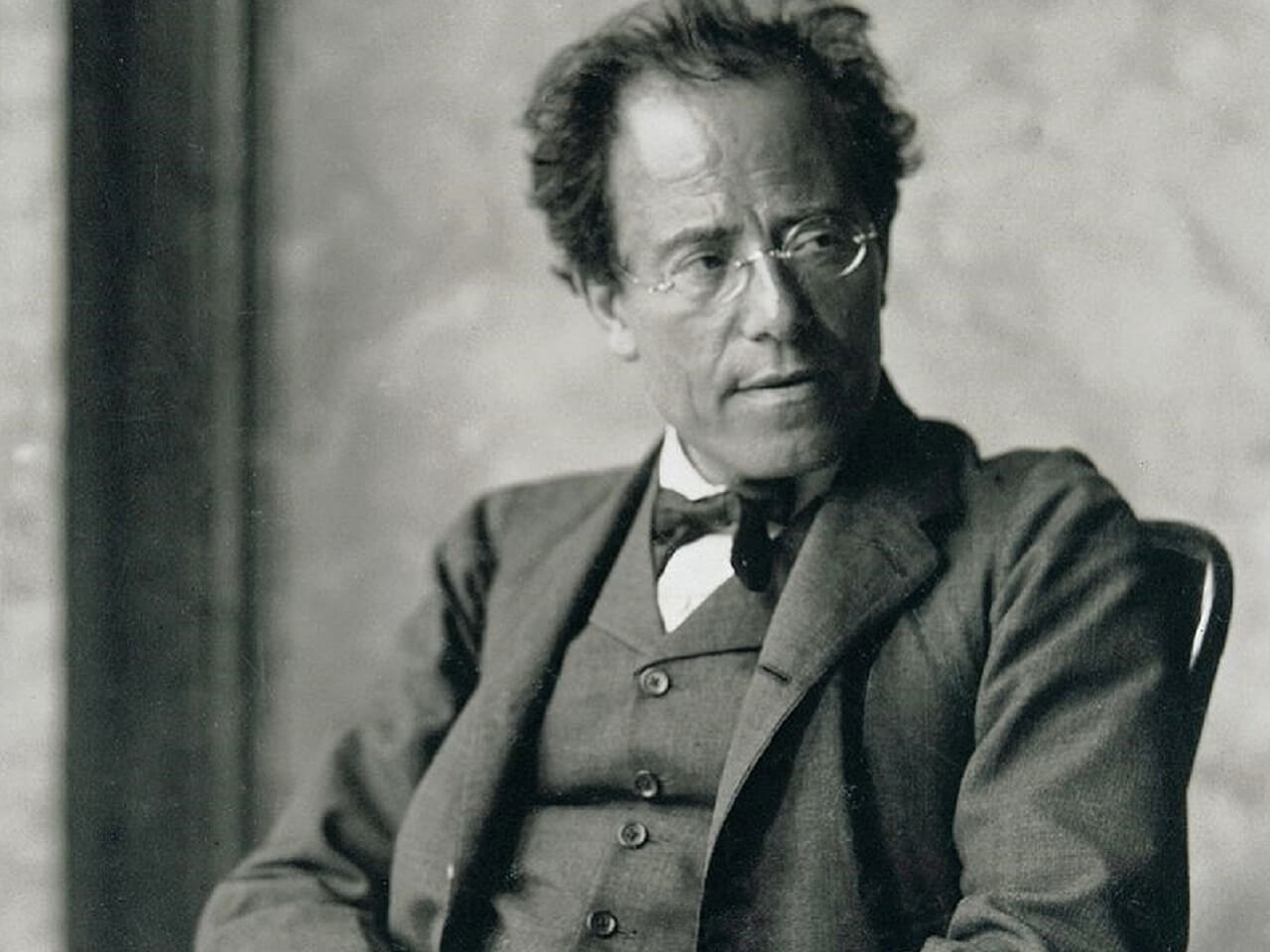

On July 7, 1860, 160 years ago, in Kaliště, a village on the border with Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire, was born to a family of Jewish merchants of German origins the composer and conductor with whom the symphony experienced triumph and crisis: Gustav Mahler (1860–1911).

Jewish by birth and in 1897 baptized, this Bohemian musician is remembered for his nine and a half symphonies and equally for his various song cycles with orchestra, in which different aspects of Romanticism are combined. Although his music was rejected for the most part until the early 1960s, Mahler was later regarded as an important forerunner of 20th-century musical developments.

His music was labeled as Entartete Musik, or “degenerate music.” With this label, Jewish musicians —also Slavic and, in general, non-Aryan — were prohibited from playing music in the countries of the Third Reich.

Censorship affected composers — past and present — performers, atonal and avant-garde music as well as jazz, swing, and anything associated with black American music. And so it was that composers such as Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Mahler, Schoenberg, Weill, Hindemith, Stravinsky, and Gershwin were considered as carriers of non-German elements and came under attack, whereas Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Weber, Schumann, Brahms, Wagner, and Bruckner were seen as masters of a musical language that was purely Germanic and resounded everywhere in the Third Reich.

Mahler’s life in Vienna was made stormy by an increasing anti-Semitism. The Reichspost, a daily newspaper, wrote on April 14, 1897: “In our edition of 10 April we printed a note on the person of the newly appointed Opera Conductor, Mahler. At the time we already had an inkling of the origin of this celebrity and we therefore avoided publishing anything other than the bare facts[.] … The Jews’ press will see whether the panegyrics with which they plaster their idol at present do not become washed away by the rain of reality as soon as Herr Mahler starts spouting his Yiddish interpretations from the podium” (J.M. Fischer, Gustav Mahler, Yale University Press, 2013, p. 252). He was ultimately driven from his post by a venomous press campaign in 1907 that alleged “mismanagement” of the Vienna Court Opera on Mahler’s part.

Isn’t the 160th anniversary of the birth of this problematic musician an opportunity to listen to his symphony, which he considered the highest musical expression? We propose his Symphony No. 2, Resurrection: one hour and twenty of music, composed between 1887 and 1894, when Mahler was director of the Budapest and Hamburg Opera House, which makes use of an orchestra of remarkable proportions (to which four horns and four trumpets “in lontananza,” in the distance, useful for particular sound effects, are added), of soprano and alto solos, mixed choir and organ, and has five movements instead of the traditional four.

John Paul II, speaking about this symphony — which, together with symphonies Nos. 3, 4, and 8, could be called “symphony-cantata” — said: “In it the cry of man has been re-proposed, who, even in a condition of death, asks to live, revealing his powerful and incoercible longing for a resurrection and a light, which will illuminate him to eternal bliss” (John Paul II, Remarks at the conclusion of the Symphonic Concert offered by the Italian Television, RAI, November 11, 1989).

The last movement, in particular, includes the hymn Die Auferstehung (The Resurrection) by the German poet Friedrich Klopstock (1724–1803), reworked by the composer, which gives the title to the entire composition. Mahler, in a letter dated December 15, 1901, to Alma Schindler, his future wife, explains: “A voice is heard crying aloud: the end of all living beings is come, the Last Judgment is at hand and the horror of the day of days has broken forth. The earth quakes, the graves burst open, and the dead arise and stream on in endless procession. The great and the little ones of the earth — kings and beggars, righteous and godless — all press on; the cry for mercy and forgiveness strikes fearfully on our ears. The wailing rises higher, our senses desert us; consciousness dies at approach of the eternal spirit. The ‘Last Trump’ is heard — the trumpets of the Apocalypse ring out; in the eerie silence that follows, we can just catch the distant, barely audible song of the nightingale, a last tremulous echo of earthly life! a chorus of saints and heavenly beings softly breaks forth: ‘Thou shalt arise, surely thou shalt rise!’ Then appears the glory of God! A wondrous, soft light penetrates us to the heart — all is holy calm!” (A. Mahler, Gustav Mahler, Memories and Letters, London: Murray, 1973, pp. 213–214).

You never know: some adolescent looking for meaning for his life might feel God’s presence, listening to this music, as in 1989 happened to a fifteen-year-old boy, who is now the Reverend Fr. Erik Varden, OCSO, bishop-prelate of Trondheim, Norway. This is his story:

I was close to 16, developing an interest in Mahler. Having splashed my savings on a CD player, I bought a Bernstein recording of his Second Symphony, the Resurrection. The Christian significance of the theme was known to me, but left me cold. Although I had been baptized, I had never affirmed belief. If anything, I was hostile. Christianity appeared to me a wishful flight away from the inner drama I was trying to negotiate, which was full of ambivalence, far distant from the studied certainties of preachers. … As I listened to the symphony, I could not remain aloof. I had not expected to be so moved. … The fifth, final movement arises like a thunderstorm. It conjures up images of chaos. … Gradually, a rhythmic theme forms within what might pass as mere noise. … “Have faith: you were not born in vain. You have not lived or suffered in vain.” At these words, something burst. … A voice sang within me: “not in vain!” Mahler let me sense that one can face life without yielding to despondency or madness, since the anguish of the world is embraced by an infinite benevolence investing it with purpose. (E. Varden, The Shattering of Loneliness: On Christian Remembrance, London: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2018)