Growing up in the United Methodist Church I was blissfully unaware of liturgical debates and differences within Christianity. Our church was what I’d call “Middle Church”—we didn’t embrace all the liturgical riches of High Church Anglicanism, nor did we succumb to the antics of Low Church Evangelicalism. In other words, we were solidly Midwest Boring.

When I became Catholic in the early 1990s, the Mass I attended wasn’t much different in tone than what I experienced at my Methodist Church. There was no incense, no bells, no chant; nor was there extemporaneous prayers and modern music. So I felt comfortable in that setting. Although I had converted to Catholicism, my liturgical understanding was still predominantly Methodist.

A few years after my conversion my pastor invited me to an ecumenical meeting of Catholics and Eastern Orthodox. Soon after that meeting I attended my first Eastern (Catholic) Divine Liturgy. I was mesmerized. This experience opened my eyes to what a liturgy could—and should—be. I began to read more and more about the liturgy, from both Eastern and Western Christian sources, and began a path to a decidedly “High Church” outlook to liturgy which eventually led me to where I am now: a regular attender of the traditional Latin Mass (TLM).

Perhaps because it began in the East and ended in traditional Rome, my liturgical path never led me to think that one specific liturgy was the only one all Christians should attend. I loved the diversity of the Eastern rites, while also appreciating the traditional Roman Rite. As I studied more liturgical history, in fact, I began to wish that the West had kept its own diversity more than it did.

Before the 16th century Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church had no one set Western liturgy: the Roman, the Ambrosian, the Dominican, the Sarum, and other rites were commonly celebrated across Western Europe. Even within each rite existed differences around the continent. All these liturgies were interrelated, of course, but with various differences that had developed over time.

In response to the chaos of the Reformation, Pope Pius V made the Roman Rite (what we today call the traditional Latin Mass) the primary liturgy of the Church. He allowed exceptions for liturgies over 200 years old, but in practice the Roman Rite became the sole rite of the Latin Church.

While the pope’s decision was sensible in the face of widespread doctrinal, sacramental, and liturgical confusion, I can’t help but think it was unfortunate that Western liturgical diversity was squelched.

In traditional Catholic circles, liturgical diversity today is understandably held in suspicion, as it typically points to the endless options of the Novus Ordo or cooked-up liturgies like the “Amazonian Rite” that have no connection to Catholic tradition. But authentic and organic Catholic liturgical development has historically resulted in diversity.

Organic and diverse development is what happened with the various Eastern liturgies, and that’s what happened in the West as well, at least before Pius V restrained that development. (In fact, it could be argued that the radical and inorganic liturgical changes of the 1960’s were in part an unfortunate result of bottled-up legitimate desires for liturgical development and diversity over the previous 400 years.)

One of the most significant ways liturgy organically develops is by taking on aspects of the culture in which it is celebrated. Diversity is found in the significant differences between the Western and Eastern rites, and it’s also seen in the various differences between the many Eastern rites themselves. Liturgical differences involve language, tone, and temperament, which reflect the culture of those who participate in it. Again, these differences aren’t something invented at meetings of professional liturgists, but develop naturally over time.

As a Western Christian, I have always been most comfortable at Western liturgies. I absolutely love the Eastern rites, but they’ve never felt as “natural” as the traditional Latin Mass does to me. For me, attending the Eastern Divine Liturgy is like a wonderful vacation, but the ancient Roman Rite is home—I am decidedly Western in temperament.

But I’m not just a Western Christian; my background is more specific than that. Methodism is an offshoot of Anglicanism, being founded in England by the Anglican priest John Wesley in the 18th century. Further, my ancestry is deeply English, and because of that, I am quite the Anglophile American. So what about a Catholic liturgy that is not only Western, but English? Wouldn’t that be something?

Well, such a liturgy exists: the Ordinariate Mass. The history of this liturgy is a bit confusing, but I’ll give the basics here. In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI established what are called the “Ordinariates,” which were ecclesial structures for Anglican converts with Anglican-influenced liturgical practices. Many Anglicans, both cleric and lay, were becoming Catholic, but they lamented that they had to abandon many of their Anglican traditions that weren’t contradictory to Catholicism. So the pope generously set up a means by which they could continue to celebrate those traditions within the Catholic Church.

One of these traditions is a liturgy based on the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), which is the controlling liturgical and prayer book of the Anglican Church. The BCP dates back to the 16th century, and it is well-known for containing some of the most beautiful English-language prayers in existence—it brought Elizabethan English, the language of Shakespeare, to the liturgy. The BCP liturgy was also originally based on the Sarum Rite, a liturgy originating in medieval Salisbury, England and closely related to the Roman Rite. The goal of the Ordinariate then was to merge this beautiful linguistic and liturgical tradition with a fully Catholic theology and outlook.

As can be seen, the Ordinariate Mass has had an eclectic history, encompassing the English Sarum Rite, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, and the ancient Roman Rite, with some (unfortunate) influences from the modern Novus Ordo liturgy as well.

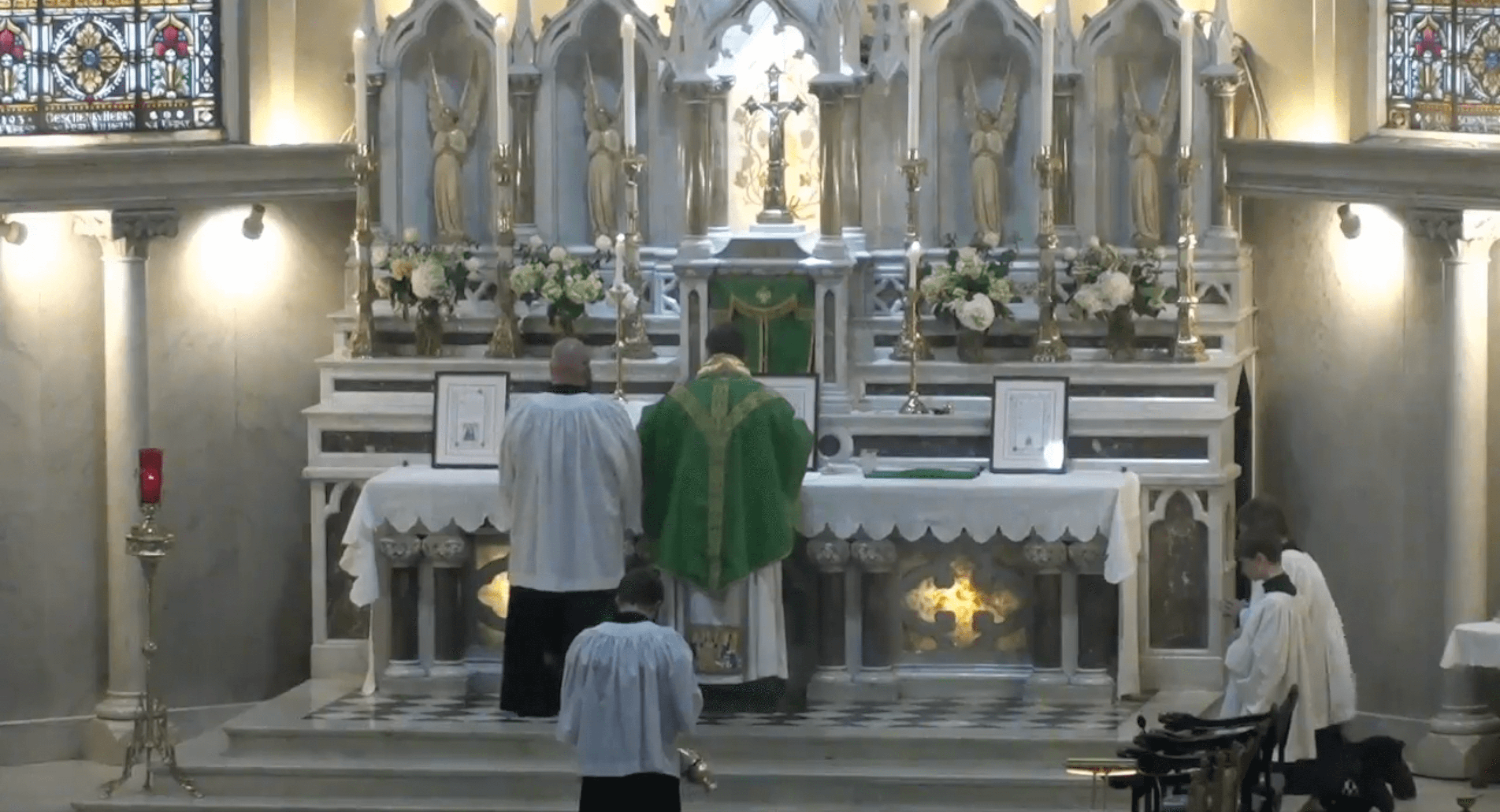

I had heard about and was intrigued by the Ordinariate Mass for a long time, but recently I was traveling in a town where the Ordinariate Mass is celebrated. So with my family I attended for the first time.

Since I regularly attend a TLM in a beautiful church and with wondrous sacred music, I was not awestruck by the Ordinariate Mass as Catholics who regularly attend a typical Novus Ordo might be. I am used to reverence in the liturgy, ad orientem worship, and theologically rich prayers.

In fact, because of my association with the TLM, it was jarring to witness a Western liturgy in English that was not irreverent. Decades of attending Novus Ordo Masses conditioned me to expect a certain casualness and even sloppiness to be attached to an English-speaking liturgy (yes, there are Novus Ordo exceptions, but these are few and far-between). In the Ordinariate Mass you have all the reverence and deep theology you find in the traditional Latin Mass, but the whole liturgy is in English.

I know many faithful TLM-goers argue that a liturgical language like Latin is superior to the vernacular, and I respect those arguments. Latin is the language of the Latin Church, and it should always be given a certain pride of place. But I am not someone who believes the Latin language should be required for all Western liturgies. Also, it’s important to remember that the Ordinariate Mass is not in common English, it is a sacral English. For example, here is the Collect for Purity said at the beginning of Mass:

Almighty God, unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord.

This is not how we speak to each other, and it is fitting that we use more formal language to liturgically pray to God. It reminds our brains that what we do in the liturgy is not common speech, but the worship of Almighty God. You find a similar principle in the Eastern liturgies, which are often celebrated in old forms of the vernacular, such as Church Slavonic.

I have to admit I prefer the liturgy in this sacral English rather than Latin. I found it helped me to focus on what was being said better than Latin does, while still retaining the mystery one should find in a Catholic liturgy. But I acknowledge that this is a personal preference, and others have good reasons for their preferences. This is where legitimate liturgical diversity should be fostered. It’s not a matter of creating test-tube liturgies in committees and then foisting them upon the people; instead, cultures influence the development of liturgies over time, under the watchful eye of the Church.

Many have described the Ordinariate Mass as “the traditional Latin Mass but in English.” While not completely accurate, I can understand why this is a common descriptor. Many of the prayers and the structure of the Ordinariate Mass are similar (or identical) to the TLM, and it’s much closer to the TLM than the Novus Ordo. In fact, attending an Ordinariate Mass exposes the common misunderstanding among many Catholics that the only difference between the Novus Ordo and the TLM is the language in which they are celebrated. By seeing firsthand how different the Ordinariate Mass is from the Novus Ordo, you understand quite clearly that the Novus Ordo is not the TLM in English; the Novus Ordo is, in fact (unlike the Ordinariate Mass) a radically different liturgy from the TLM.

While the Ordinariate Mass is far more similar to the TLM than the Novus Ordo, it has its own history and its own liturgical specifics that differ from the TLM. For example, the Ordinariate Mass does not require the penitential prayers at the foot of the altar at the beginning of Mass as the TLM does. However, it does have a Collect for Purity and a Summary of the Law immediately following the opening Sign of the Cross, and then a Penitential Rite after the Creed and before the Offertory:

Almighty God, Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, maker of all things, judge of all men: We acknowledge and bewail our manifold sins and wickedness, which we from time to time most grievously have committed, by thought, word, and deed, against thy divine majesty, provoking most justly thy wrath and indignation against us. We do earnestly repent, and are heartily sorry for these our misdoings; the remembrance of them is grievous unto us, the burden of them is intolerable. Have mercy upon us, have mercy upon us, most merciful Father; for thy Son our Lord Jesus Christ’s sake, forgive us all that is past; and grant that we may ever hereafter serve and please thee in newness of life, to the honour and glory of thy Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

This is followed by a “Prayer for Pardon” and some “Comfortable Words” which repeat a few Scriptural passages about the mercy of God.

The Anglican history of the Ordinariate has led some Catholics to be hesitant about embracing the Catholicity of the Ordinariate Mass; after all, the BCP and Anglicanism itself were founded on a rejection of the papacy and the ruthless suppression of Catholicism in England. How can this be redeemed? Isn’t this just an example of watered-down Catholicism, of ecumenism gone amok?

Although I am a fierce critic of the modern ecumenical movement, I think this particular ecumenical move was a good one. The whole point of the ecumenical movement should be to unite Christians into one body, and as Catholics we know (or should know) that it is only in the Catholic Church that unity can occur. So to give a means by which non-Catholics can more easily enter the Catholic Church, without compromising our faith, is a wonderful thing. And if you look closely at the Ordinariate Mass, you can see it is fully and unapologetically Catholic.

While I am completely happy with attending the TLM at my parish, I hope and pray for the growth of the Ordinariate. First and foremost, it makes available a clear path for the conversion of Anglicans to Catholicism. It also makes reverent, theologically-rich liturgies available to more Catholics. And finally, it brings about more legitimate liturgical diversity within Western Catholicism.

To be clear, this is not intended to present the Ordinariate Mass as an alternative to the TLM if the latter is shut down, nor even as a replacement for the Novus Ordo. The Ordinariate Mass is not a “safety valve” for Trads. That’s not fair to the Ordinariate Mass, nor is it realistic. There are rumors, after all, that the Vatican will crack down on the Ordinariates after it finishes abolishing the TLM, since Traditionis Custodes argues that there should be only one form of the Roman Rite (I would argue that the Ordinariate Mass is not a form of the Roman Rite but a separate Western rite, but such details are rarely considered in the current push for liturgical uniformity). The Ordinariate Mass should stand on its own, as one of many Western liturgical rites.

There’s legitimate reason to worry about the future of all the ancient rites of the Church, but for now I’m thankful that the Ordinariate is available to English-speaking Catholics. It is my prayer that the traditional Latin Mass and the Ordinariate Mass—as well as the Eastern liturgies and other ancient Western liturgies—all flourish in the Church, glorifying God in diverse ways.