Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article was first published at OnePeterFive in October 2015 under the pen name “Benedict Constable.” Due to some controversy (the nature of which need not be gone into here), the article was taken down, but not before it had reached a large number of readers and received praise as one of the most helpful responses yet penned to the present crisis in Church authority. The author has extensively revised the article for republication, benefiting from the feedback of a number of readers, including church historians and dogmatic theologians. It is also being published under the author’s proper name.

There are those in the Church who cannot bear to see a pope criticized for any reason – as if the whole Catholic Faith would come tumbling down were we to show that a particular successor of Peter was a scoundrel, murderer, fornicator, coward, compromiser, ambiguator, espouser of heresy, or promoter of faulty discipline. But it is quite false that the Faith would come tumbling down; it is far stronger, stabler, and sounder than that, because it does not depend on any particular incumbent of the papal office. Rather, it precedes these incumbents; outlasts them; and, in fact, judges them as to whether they have been good or bad vicars of Christ. The Faith is entrusted to the popes, as it is to the bishops, but it is not subject to their control.

The Catholic Faith comes to us from God, from Our Lord Jesus Christ, who is the Head of the Church, its immovable cornerstone, its permanent guarantee of truth and holiness [1]. The content of that Faith is not determined by the pope. It is determined by Christ and handed down in Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium – with the Magisterium understood not as anything and everything that emanates from bishops or popes, but as the cumulative public, official, definitive, and universal teaching of the Church enshrined in dogmatic canons and decrees, anathemas, bulls, encyclicals, and other instruments of teaching in harmony with the foregoing.

One serious problem that faces us is a “papalism” that blinds Catholics to the reality that popes are peccable and fallible human beings like the rest of us, and that their pronouncements are guaranteed to be free from error only under strictly delimited conditions [2]. Apart from that, the realm of papal ignorance, error, sin, and disastrous prudential governance is broad and deep – although secular history affords no catalog of greatness comparable to the nearly 100 papal saints, and plenty of worse examples than the worst popes, which says a lot about man’s fallen condition.

At a time when Catholics are confused about whether and how a pope can go wrong, it seems useful to compile examples in three categories: (1) times when the popes were guilty of grave personal immorality; (2) times when popes connived at or with heresy, or were guilty of a harmful silence or ambiguity in regard to heresy; (3) times when popes taught (albeit not ex cathedra) something heretical, savoring of heresy, or harmful to the faithful.

Not everyone may agree that every item listed is, in fact, a full-blooded example of the category in question, but that is beside the point; the fact that there are a number of problematic instances is sufficient to show that popes are not automatic oracles of God who hand down only what is good, right, holy, and laudable. If that last statement seems like a caricature, one need only look at how conservative Catholics today are bending over backward to get lemonade out of every lemon offered by Pope Francis and denying with vehemence that Roman lemons could ever be rotten or poisonous.

Popes Guilty of Grave Personal Immorality

This, sadly, is an easy category to fill, and it need not detain us much. One might take as examples six figures about whom E.R. Chamberlin wrote his book The Bad Popes [3].

- John XII (955-964) gave land to a mistress, murdered several people, and was killed by a man who caught him in bed with the man’s wife.

- Benedict IX (1032-1044, 1045, 1047–1048) managed to be pope three times, having sold the office off and bought it back again.

- Urban VI (1378-1389) complained that he did not hear enough screaming when cardinals who had conspired against him were tortured.

- Alexander VI (1492-1503) bribed his way to the throne and bent all of his efforts to the advancement of his illegitimate children, such as Lucrezia, whom at one point he made regent of the papal states, and Cesare, admired by Machiavelli for his bloody ruthlessness. In his reign, debauchery reached an unequaled nadir: for a certain banquet, Alexander VI brought in fifty Roman prostitutes to engage in a public orgy for the viewing pleasure of the invited guests. Such was the scandal of his pontificate that his clergy refused to bury him in St. Peter’s after his death.

- Leo X (1513-1521) was a profligate Medici who once spent a seventh of his predecessors’ reserves on a single ceremony. To his credit, he published the papal bull Exsurge Domine (1520) against the errors of Martin Luther, within which he condemned, among others, the proposition: “That heretics be burned is against the will of the Spirit” (n. 33).

- Clement VII (1523-1534), also a Medici, by his power-politicking with France, Spain, and Germany, managed to get Rome sacked.

There are others one could mention.

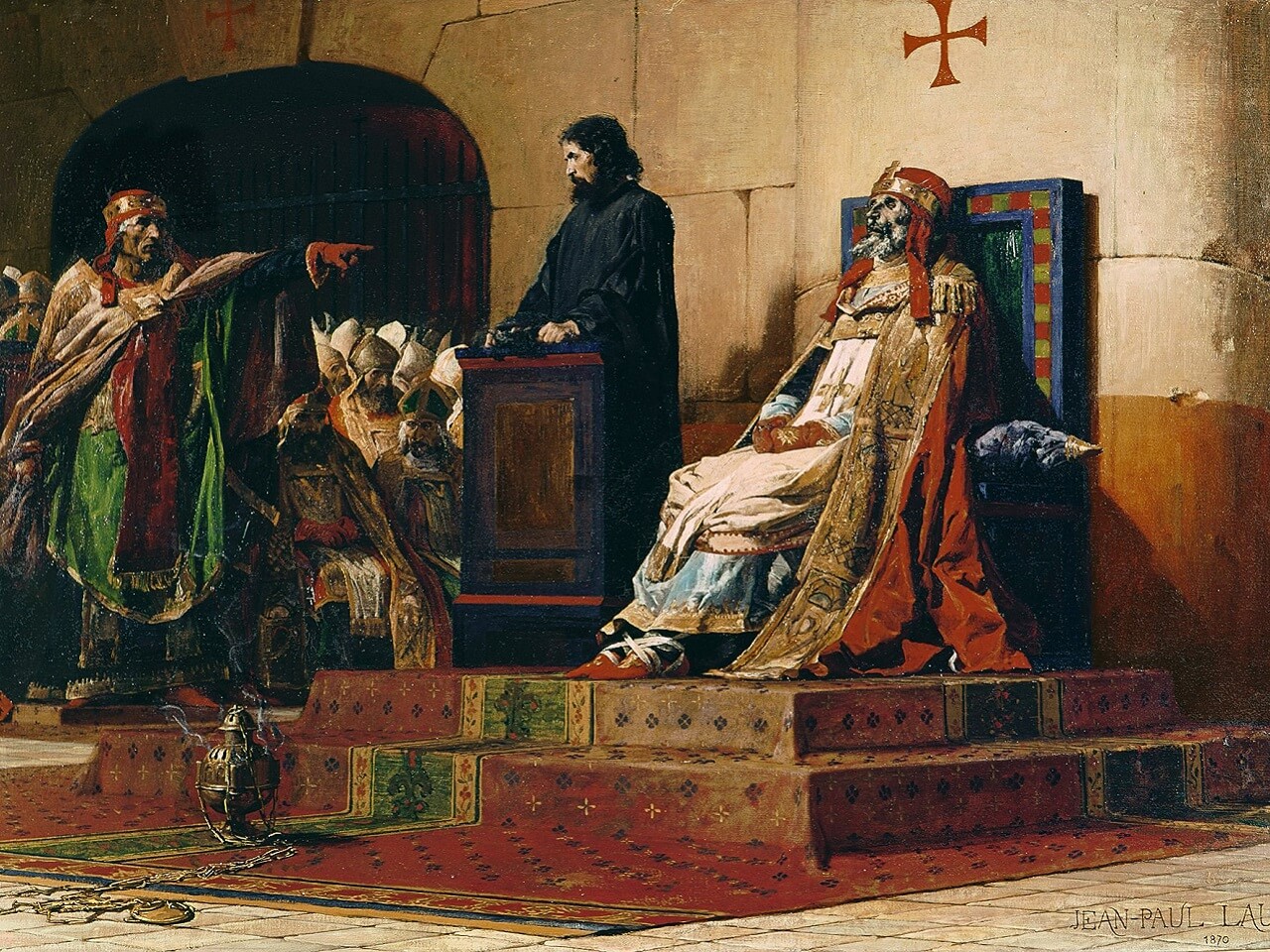

- Stephen VII (896-897) hated his predecessor, Pope Formosus, so much that he had him exhumed, tried, de-fingered, and thrown in the Tiber, while (falsely) declaring ordinations given at his hands to have been invalid. Had this ill advised declaration stood, it would have affected the spiritual lives of many, since the priests would not have been confecting the Eucharist or absolving sins.

- Pius II (1458-1464) penned an erotic novel before he became pope.

- Innocent VIII (1484-1492) was the first pope to acknowledge officially his bastards, loading them with favors.

- Paul III (1534-1549), who owed his cardinalate to his sister, the mistress of Alexander VI, and himself the father of bastards, made two grandsons cardinals at the ages of 14 and 16 and waged war to obtain the Duchy of Parma for his offspring.

- Urban VIII (1623-1644) engaged in abundant nepotism and supported the castration of boys so they could sing in his papal choir as castrati. Cardinals denounced him, with Cardinal Ludovisi actually threatening to depose him as a protector of heresy.

There are debates about the extent of the wrongdoing of some of these popes, but even with all allowances made, we must admit there is a papal hall of shame.

Popes Who Connived at Heresy or Were Guilty of Harmful Silence or Ambiguity

Pope St. Peter (d. ca. 64). It may seem daring to begin with St. Peter, but after all, he did shamefully compromise on the application of an article of faith, viz., the equality of Jewish and Gentile Christians and the abolition of the Jewish ceremonial law – a lapse for which he was rebuked to his face by St. Paul (cf. Gal 2:11). This has been commented on so extensively by the fathers and doctors of the Church and by more recent authors that it needs no special treatment here. It should be pointed out that Our Lord, in His Providence, allowed His first vicar to fail more than once so that we would not be scandalized when it happened again with his successors. This, too, is why he chose Judas: so the treason of bishops would not cause us to lose faith that He remains in command of the Church and of human history.

Pope Liberius (352-366). The story is complicated, but the essentials can be told simply enough. The Arian emperor Constantius had, with typical Byzantine arrogance, “deposed” Liberius in 355 for not subscribing to Arianism. After two years of exile, Liberius came to some kind of accord with the still Arian emperor, who then permitted him to return to Rome. What compromise doctrinal formula he signed or even whether he signed it is unknown (St. Hilary of Poitiers asserted that he had), but it is surely not without significance that Liberius, the 36th pope, is the only one among 54 popes from St. Peter to St. Gelasius I who is not revered as a saint in the West. At least in those days, popes were not automatically canonized, especially if they messed up on the job and failed to be the outstanding shepherds they should have been.

Pope Vigilius (537-555). The charges against Vigilius are four. First, he made an intrigue with the empress Theodora, who offered to have him installed as pope in return for his reinstating the deposed Anthimus in Constantinople [4]. Second, he usurped the papacy. Third, he changed his position in the affair of the Three Chapters (writings that were condemned by the Eastern bishops for going too far in an anti-Monophysite direction). Vigilius at first refused to agree to the condemnation, but when the Second Council of Constantinople confirmed it, Vigilius was prevailed on by imperial pressure to ratify the conciliar decree. It seems that Vigilius recognized the condemnation of the Three Chapters as problematic because it was perceived in the West as undermining the doctrine of the Council of Chalcedon but nevertheless allowed himself to be cajoled into doing so. Fourth, his wavering on this question and his final decision were responsible for a schism that ensued in the West, since some of the bishops of Italy refused to accept the decree of Constantinople. Their schism against both Rome and the East was to last for many years [5].

Pope Honorius I (625-638). In their efforts to reconcile the Monophysites of Egypt and Asia, the Eastern emperors took up the doctrine of Monothelitism, which proposed that, while Christ has two natures, He has only one will. When this was rejected by theologians as also heretical, the further compromise was advanced that, although Christ has two wills, they have nevertheless only “one operation” (hence the name of the doctrine, Monenergism). This, too, was false, but the patriarch of Constantinople made efforts to promote reunion by stifling the debate and forbidding discussion of the matter. In 634, he wrote to Pope Honorius seeking support for this policy, and the pope gave it, ordering that neither expression (“one operation” or “two operations”) should be defended. In issuing this reply, Honorius disowned the orthodox writers who had used the term “two operations.” More seriously, he gave support to those who wished to fudge doctrinal clarity to conciliate a party in rebellion against the Church.

Fifteen years later, the Emperor Constans II published a document called the Typos in which he ordained precisely the same policy that Honorius had done. However, the new pope, Martin I, summoned a synod that condemned the Typos and upheld the doctrine of two operations. An enraged Constans had Martin brought to Constantinople and, after a cruel imprisonment, exiled him to the Crimea, where he died, for which reason he is revered as a martyr – the last of the papal martyrs (so far). In 680-681, after the death of Constans, the Third Council of Constantinople was held, which discarded the aim of harmony with the Monophysites in favor of that with Rome. Flaunting solidarity with the persecuted Martin, it explicitly and famously disowned his predecessor: “We decide that Honorius be cast out of the holy Church of God.” The then reigning pope, Leo II, in a letter accepting the decrees of this council, condemned Honorius with the same forthrightness: “We anathematize Honorius, who did not seek to purify this apostolic Church with the teaching of apostolic tradition, but by a profane betrayal permitted its stainless faith to be surrendered.” In a letter to the bishops of Spain, Pope Leo II again condemned Honorius as one “who did not, as became the apostolic authority, quench the flame of heretical doctrine as it sprang up, but quickened it by his negligence” [6].

Pope John Paul II (1978-2005). John Paul II designed the gathering of world religions in Assisi in 1986 in such a way that the impression of indifferentism as well as the commission of sacrilegious and blasphemous acts were not accidental, but in accord with the papally approved program. His kissing of the Koran is all too well known. He was thus guilty of dereliction in his duty to uphold and proclaim the one true Catholic Faith and gave considerable scandal to the faithful [7].

Popes Who Taught Something Heretical, Savoring of Heresy, or Harmful to the Faithful

Here we enter into more controversial territory, but there can be no doubt that the cases listed below are real problems for a papal positivist or ultramontanist, in the sense that the latter term has recently acquired: one who overstresses the authority of the words and actions of the reigning pontiff as if they were the sole or principal standard of what constitutes the Catholic Faith.

Pope Paschal II (1099-1118). In his desire to obtain cooperation from Emperor Henry V, Pope Paschal II reversed the policy of all of his predecessors by conceding to the emperor the privilege of investiture of bishops with the ring and crosier, which signified both temporal and spiritual power. This concession provoked a storm of protest throughout Christendom. In a letter, St. Bruno of Segni (c. 1047-1123) called Pope Paschal’s position “heresy” because it contradicted the decisions of many church councils and argued that whoever defended the pope’s position also became a heretic thereby. Although the pope retaliated by removing St. Bruno from his office as abbot of Monte Cassino, eventually Bruno’s argument prevailed, and the pope renounced his earlier decision [8].

Pope John XXII (1316-1334). In his public preaching from November 1, 1331 to January 5, 1332, Pope John XXII denied the doctrine that the just souls are admitted to the beatific vision, maintaining that this vision would be delayed until the general resurrection at the end of time. This error had already been refuted by St. Thomas Aquinas and many other theologians, but its revival on the very lips of the pope drew forth the impassioned opposition of a host of bishops and theologians, among them Guillaume Durand de Saint Pourçain, Bishop of Meaux; the English Dominican Thomas Waleys, who, as a result of his public resistance, underwent trial and imprisonment; the Franciscan Nicholas of Lyra; and Cardinal Jacques Fournier. When the pope tried to impose this erroneous doctrine on the Faculty of Theology in Paris, the king of France, Philip VI of Valois, prohibited its teaching and, according to accounts by the Sorbonne’s chancellor, Jean Gerson, even reached the point of threatening John XXII with burning at the stake if he did not make a retraction. The day before his death, John XXII retracted his error. His successor, Cardinal Fournier, under the name Benedict XII, proceeded forthwith to define ex cathedra the Catholic truth in this matter. St. Robert Bellarmine admits that John XXII held a materially heretical opinion with the intention of imposing it on the faithful but was never permitted by God to do so [9].

Pope Paul III (1534-1549). In 1535, Pope Paul III approved and promulgated the radically novel and simplified breviary of Cardinal Quignonez, which, although approved as an option for the private recitation of clergy, ended up in some cases being implemented publicly. Some Jesuits welcomed it, but most Catholics – including St. Francis Xavier – viewed it with grave misgivings and opposed it, sometimes violently, because it was seen as an unwarrantable attack on the liturgical tradition of the Church [10]. Its very novelty constituted an abuse of the lex orandi and therefore of the lex credendi. It was harmful to those who took it up because it separated them from the Church’s organic tradition of worship; it was a private person’s fabrication, a rupture with the inheritance of the saints. In 1551, Spanish theologian John of Arze submitted a strong protest against it to the Fathers of the Council of Trent. Fortunately, Pope Paul IV repudiated the breviary by rescript in 1558, some 23 years after its initial papal approval, and Pope St. Pius V altogether prohibited its use in 1568. Thus, five popes and 33 years after its initial papal approval, this mangled “on the spot product” was buried [11].

Pope Paul VI (1963-1978). As the pope who promulgated all of the documents of the Second Vatican Council, whatever problems are contained in those documents – and these problems [12], neither insignificant nor few in number, have been identified by many – must be laid at the feet of Paul VI. One might, for example, point out materially erroneous statements in Gaudium et Spes (e.g., n. 24, which asserts that “love of God and neighbor is the first and greatest commandment” [13], or n. 63, which asserts that “man is the source, the center, and the purpose of all economic and social life” [14]), but it is perhaps the Declaration on Religious Liberty Dignitatis Humanae (December 7, 1965) that will go down in history as the low water mark of this assembly. Like some kind of frenzied merry-go-round, the hermeneutical battles over this document will never stop until it is definitively set aside by a future pope or council. In spite of Herculean (and verbose) attempts at reconciling D.H. with the preceding magisterium, it is at least prima facie plausible that the document’s assertion of a right to hold and propagate erroneous religious beliefs, even if they be misunderstood by their partisans as truth, is contrary both to natural reason and to the Catholic faith [15].

Far worse than this is the first edition of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, promulgated with the signature of Paul VI on April 3, 1969, which contained formally heretical statements on the nature of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. When a group of Roman theologians headed by Cardinals Ottaviani and Bacci pointed out the grave problems, the pope ordered the text to be corrected so that a second revised edition could be brought out. In spite of the fact that the differences in the text are astonishing, the first edition was never officially repudiated, nor was it ordered to be destroyed; it was merely replaced [16]. Moreover, although expounding the claim would exceed the scope of this article, the promulgation of the Novus Ordo Missae itself was both a dereliction of the pope’s duty to protect and promote the organic tradition of the Latin Rite and an occasion of immense harm to the faithful.

Pope John Paul II asserted on multiple occasions a right to change one’s religion, regardless of what that religion may be. This is true only if you hold to a false religion, because no one is bound to what is false, whereas everyone is bound to seek and adhere to the one true religion. If you are a Catholic, you cannot possibly have a right, either from nature or from God the author of nature, to abandon the Faith. Hence, a statement such as this: “Religious freedom constitutes the very heart of human rights. Its inviolability is such that individuals must be recognized as having the right even to change their religion, if their conscience so demands” [17] is false taken at face value – and dangerously false, one might add, because of its liberal, naturalistic, indifferentist conceptual foundation.

Pope Francis. One hardly knows where to begin with this egregious doctor (and I do not mean it in the complimentary sense of doctor egregius). Indeed, an entire website, Denzinger-Bergoglio, has been established by philosophers and theologians who have listed in painstaking detail all of the statements of this pope that have contradicted Sacred Scripture and the Magisterium of the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, we may identify several particularly dangerous false teachings.

(1) The explicit approval of giving Holy Communion to divorced and “remarried” Catholics who have no intention of living as brother and sister, expressed as a possibility in the post-synodal apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia and confirmed as a reality in the letter to the bishops of Buenos Aires published in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis [18].

(2) The attempted change in teaching on capital punishment, first raised in a speech in October 2017 and now imposed on the Church by means of a change to the Catechism, in spite of the fact that the new doctrine manifestly goes against a unanimous tradition with its roots in Scripture [19]. The worst aspect of this change, as many have already pointed out, is that it loudly transmits the signal, most welcome to progressives, liberals, and modernists, that doctrines handed down over centuries or millennia, printed in every penny catechism that has ever rolled off the printing press, are up for revision, even to the point of saying the opposite, when the Zeitgeist pipes and the pope dances to the tune. There is no telling what further “development of doctrine” is in store for us enlightened moderns who see so much farther into the moral law than our barbaric predecessors. Ordination of females, overcoming the last vestiges of primitive patriarchalism? Legitimization of contraception and sodomy, finally letting go of the reductionistic biologism that has plagued Catholic moral teaching with the bugbear of “intrinsically disordered acts”? And so on and so forth.

As a Benedictine friend of mine likes to say: “The issue is not the issue.” A Dominican priest perceptively wrote: “This isn’t about the death penalty. It’s about getting language into the Catechism that allows theologians to evaluate doctrine/dogma in historicist terms; that is, ‘This truth is no longer true because times have changed.’ The Hegelians got their wish.”

(3) The annulment reforms, which amount, in practice, to an admission of “Catholic divorce” because of the novel concept of a “presumption of invalidity” [20].

This overview, from Paschal II to Francis, suffices to allow us to see one essential point: if heresy can be held and taught by a pope, even temporarily or to a certain group, it is a fortiori possible that disciplinary acts promulgated by the pope, even those intended for the universal Church, may also be harmful. After all, heresy in itself is worse than lax or contradictory discipline.

* * *

Melchior Cano, an eminent theologian at the Council of Trent, famously said:

Now one can say briefly what [those do] who temerariously and without discrimination defend the supreme pontiff’s judgment concerning everything whatsoever: these people unsteady the authority of the Apostolic See rather than fostering it; they overturn it rather than shoring it up. For – passing over what was explained a little before in his chapter – what profit does he gain in arguing against heretics whom they perceive as defending papal authority not with judgment but with emotion, nor as doing so in order to draw forth light and truth by the force of his argument but in order to convert another to his own thought and will? Peter does not need our lie; he does not need our adulation. [21]

Let us return to our point of departure. The Catholic faith is revealed by God, nor can it be modified by any human being: “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and for ever” (Heb. 13:8). The pope and the bishops are honored servants of that revelation, which they are to hand down faithfully, without novelty and without mutation, from generation to generation. As St. Vincent of Lerins so beautifully explains, there can be growth in understanding and formulation, but no contradiction, no “evolution.” The truths of the Faith, contained in Scripture and Tradition, are authentically defined, interpreted, and defended in the narrowly circumscribed acta of councils and popes over the centuries. In this sense, it is quite proper to say: “Look in Denzinger – that’s the doctrine of the Faith.”

Catholicism is, has always been, and will always be stable, perennial, objectively knowable, a rock of certitude in a sea of chaos – despite the efforts of Satan and his dupes to change it. The crisis we are passing through is largely a result of collective amnesia of who we are and what we believe, together with a nervous tendency toward hero-worship, looking here and there for the Great Leader who will rescue us. But our Great Leader, our King of Kings and Lord of Lords, is Jesus Christ. We follow and obey the pope and the bishops inasmuch as they transmit to us the pure and salutary doctrine of our Lord and guide us in following His way of holiness, not when they offer us polluted water to drink or lead us to the muck. Just as our Lord was a man like us in all things except sin, so we follow them in all things except sin – whether their sin be one of heresy, schism, sexual immorality, or sacrilege. The faithful have a duty to form their minds and their consciences to know whom to follow and when. We are not mechanical puppets.

Neither are the popes: they are men of flesh and blood, with their own intellect and free will, memory and imagination, opinions, aspirations, ambitions. They can cooperate better or worse with the graces and responsibilities of their supreme office. The pope unquestionably has a singular and unique authority on earth as the vicar of Christ. It follows that he has a moral obligation to use it virtuously, for the common good of the Church – and that he can sin by abusing his authority or by failing to use it when or in the manner in which he ought to do so. Infallibility, correctly understood, is the Holy Spirit’s gift to him; the right and responsible use of his office is not something guaranteed by the Holy Spirit. Here the pope must pray and work, work and pray like the rest of us. He can rise or fall like the rest of us. Popes can make themselves worthy of canonization or of execration. At the end of his mortal pilgrimage, each successor of St. Peter will either attain eternal salvation or suffer eternal damnation. All Christians, in like manner, will become either saintly by following the authentic teaching of the Church and repudiating all error and vice or damnable by following spurious teaching and embracing what is false and evil.

I can hear an objection from some readers: “If a pope can go off the rails and stop teaching the orthodox Faith, then what’s the point of having a papacy? Isn’t the whole reason we have the vicar of Christ to enable us to know for certain the truth of the Faith?”

The answer is that the Catholic Faith preexists the popes, even though they occupy a special place vis-à-vis its defense and articulation. This Faith can be known with certainty by the faithful through a host of means – including, one might add, five centuries’ worth of traditional catechisms from all over the world that concur in their teaching. The pope is not able to say, like an absolute monarch: La foi, c’est moi.

But let us look at numbers for a moment. This article has listed eleven immoral popes and ten popes who dabbled, to one degree or another, in heresy. There have been a total of 266 popes. If we do the math, we come out with 4.14% of the Successors of Peter who earned opprobrium for their moral behavior and 3.76% who deserve it for their dalliance with error. On the other hand, about 90 of the preconciliar popes are revered as saints or blesseds, which is 33.83%. We could debate about the numbers (have I been too lenient or too severe in my lists?), but is there anyone who fails to behold in these numbers the evident hand of Divine Providence? A monarchy of 266 incumbents lasting for 2,000 years that can boast failure and success rates like this is no mere human construct, operating by its own steam.

These numbers teach us two lessons. First, we learn a sense of wonder and gratitude before the evident miracle of the papacy. We learn trust in a Divine Providence that guides the Holy Church of God throughout the tempests of ages and makes it outlast even the relatively few bad papacies we have suffered for our testing or for our sins. Second, we learn discernment and realism. On the one hand, the Lord has led the vast majority of his vicars along the way of truth so that we can know that our confidence is well placed in the barque of Peter, steered by the hand of Peter. Yet the Lord has also permitted a small number of his vicars to falter or fail so we will see that they are not automatically righteous, effortlessly wise in governance, or a direct mouthpiece of God in teaching. The popes must freely choose to cooperate with the grace of their office, or they, too, can go off the rails; they can do a better or worse job of shepherding the flock, and once in a while, they can be wolves. This happens rarely, but it does happen by God’s permissive will, precisely so we do not abdicate our reason, outsource our faith, and sleepwalk into ruin. The papal record is remarkable enough to testify to a well-nigh miraculous otherworldly power holding at bay the forces of darkness, lest the “gates of hell” prevail; but the record is speckled just enough to make us wary, keep us on our toes. The advice “be sober, be vigilant” applies not only to interactions with the world “out there,” but to our life in the Church, for “our adversary, the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour” (1 Pet 5:8), from the lowly pewsitter to the lofty hierarch.

Our teacher, our model, our doctrine, our way of life: these are all given to us, gloriously manifested in the Incarnate Word, inscribed in the fleshy tablets of our hearts. We are not awaiting them from the pope, as if they do not already exist in finished form. The pope is here to help us to believe and to do what our Lord is calling every one of us to believe and do. If any human being on the face of the Earth tries to stand in the way – be it even the pope himself – we must resist him and do what we know is right [22]. As the great Dom Prosper Guéranger wrote:

When the shepherd becomes a wolf, the first duty of the flock is to defend itself. It is usual and regular, no doubt, for doctrine to descend from the bishops to the faithful, and those who are subject in the faith are not to judge their superiors. But in the treasure of revelation there are essential doctrines which all Christians, by the very fact of their title as such, are bound to know and defend. The principle is the same whether it be a question of belief or conduct, dogma or morals. … The true children of Holy Church at such times are those who walk by the light of their baptism, not the cowardly souls who, under the specious pretext of submission to the powers that be, delay their opposition to the enemy in the hope of receiving instructions which are neither necessary nor desirable. [23]

Notes

[1] On the changelessness of the Faith that derives from Christ’s nature and mission, see my Winnipeg address and my article at OnePeterFive, “The Cult of Change and Christian Changelessness.”

[2] To understand this point better, I recommend reading the words of Fr. Adrian Fortescue and the excellent posts of Fr. Hunwicke, such as this, this, and this. This explanation of infallibility is also worthy of consideration.

I define “papalism” or its more extreme version “papolatry” as follows. If the Faith is seen more as “what the reigning pope is saying” (simply speaking) than “what the Church has always taught” (taken collectively), we are dealing with a false exaltation of the person and office of the pope. As Ratzinger said many times, the pope is the servant of Tradition, not its master; he is bound by it, not in power over it. Of course, the pope can and will make doctrinal and disciplinary determinations, but relatively few things he says are going to make the cut for formal infallibility. All that he teaches qua pope (when he seems to be intending to teach in that manner) should be received with respect and submission, unless there is something in it that is simply contrary to what has been handed down before. The examples given in my article show certain cases (admittedly rare) where good Catholics had to resist. This, I take it, is what Cardinal Burke and Bishop Schneider have also been saying: if, e.g., the synods on marriage and family or their papal byproducts attempt to force on the Church a teaching or a discipline contrary to the Faith, we cannot accept them and must resist.

[3] E. R. Chamberlin, The Bad Popes (Dorchester: Dorset Press, 1994).

[4] Following (sometimes verbatim) Henry Sire’s account in Phoenix from the Ashes (Kettering, Ohio: Angelico Press, 2015), 17-18. I recommend Sire’s book as the best analysis of modern Church history that I have yet read.

[5] He did not carry through with this move – but only because the Emperor forbade it.

[6] Again following the account in Sire, Phoenix, 18-19.

[7] See Sire, Phoenix, 384-88.

[8] Following the detailed account of Roberto de Mattei. It is true that the term “heresy” was used rather widely in earlier times, almost as shorthand for “anything that looks or sounds uncatholic,” but there is implicit in Paschal II’s temporary stance on investiture a false understanding of the true, proper, independent, divine, and non-transferable authority of the Church hierarchy vis-à-vis all temporal authority. It is, in other words, a serious matter, not a mere kerfuffle over bureaucratic procedure.

[9] For full details, see this article.

[10] See Alcuin Reid, The Organic Development of the Liturgy, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005), 37.

[11] We should not be surprised to find that, almost 400 years later, Archbishop Bugnini in 1963 expressed his unbounded admiration for the Quignonez Breviary, which in many ways served as the model for the new Liturgy of the Hours.

[12] In Phoenix from the Ashes, Henry Sire provides excellent commentary on many of the difficulties of Vatican II. One may also profitably consult Roberto de Mattei, The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story (Fitzwilliam, N.H.: Loreto, 2012). Msgr. Bruno Gherardini has made excellent contributions. Paolo Pasqualucci has provided a list of “26 points of rupture.” While I do not necessarily agree with every point Pasqualucci argues, his outline is sufficient to show what a mess the Council documents are and what an era of unclarity they have prompted. The simple fact that popes over the past fifty years have spent much of their time issuing one “clarification” after another, usually about points on which the Council spoke ambiguously (one need only think of the oceans of ink spilled on Sacrosanctum Concilium, Lumen Gentium, Dignitatis Humanae, and Nostra Aetate), is sufficient to show that it failed in the function for which a council exists: to assist Catholics in knowing their faith better and living it more fully.

[13] G.S. 24 states that “love of God and neighbor is the first and greatest commandment.” This contradicts Christ’s own words: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments” (Mt. 22:37-40). Are we required both to assent to Christ’s words that the first and greatest commandment is the love of God while the second is love of neighbor and to assent to G.S. 24 that the first and greatest commandment is the love of God-and-neighbor (cf. Apostolicam Actuositatem 8)?

While the love of God and of neighbor are intimately conjoined, love of neighbor cannot stand on the same level as the love of God, as if they were the very same commandment with no differentiation. Yes, in loving our neighbor, we do love God, and we love Christ, but God is the first, last, and proper object of charity, and we love our neighbor on account of God. We love our neighbor and even our enemies because we love God more and in a qualitatively different way: the commandment to love God befits His infinite goodness and supremacy, while the commandment to love one’s fellow man befits his finite goodness and relative place. If there were only one commandment of love, then we would be entitled to love God as we love ourselves – which would be sinful – or to love our neighbor with our whole heart, soul, and mind – which would also be sinful. In short, it is impossible for one and the same commandment to be given for the love of God and the love of neighbor.

The same erroneous view is found in Pope Francis’s Evangelii Gaudium 161: “Along with the virtues, this [observance of Christ’s teaching] means above all the new commandment, the first and the greatest of the commandments, and the one that best identifies us as Christ’s disciples: ‘This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you’ (Jn. 15:12).” Here John 15:12 has been taken for the first and greatest commandment, which it is not, according to Our Lord’s own teaching. Characteristic of the same confusion are the misleading applications of Romans 13:8,10 and James 2:8 that follow in E.G. 161, which give the impression that “the law” being spoken of is comprehensive, when in fact it refers to the moral law. In other words, to say that love of neighbor “fulfills the whole law” means that it does all that the law requires in our dealings with one another. It is not speaking of our prior obligation to love God first and more than everyone else, including our very selves.

[14] G.S. 63 claims: “Man is the source, the center, and the purpose of all economic and social life.” This might have been true in a hypothetical universe where the Son of God did not become man (although one might still have a doubt, inasmuch as the Word of God is the exemplar of all creation), but in the real universe of which the God-Man is the head, the source, and the center, the purpose of all economic and social life is and cannot be other than the Son of God, Christ the King, and, consequently, the realization of His Kingdom. Anything other than that is a distortion and a deviation. The fact that the same document says elsewhere that God is the ultimate end of man (e.g., G.S. 13) does not erase the difficulty in G.S. 63.

[15] See Sire, Phoenix, 331-358, for an excellent treatment of the problems.

[16] For details, see Michael Davies, Pope Paul’s New Mass (Kansas City: Angelus Press, 2009), 299-328; Sire, Phoenix, 249, 277-82.

[17] Message for the World Day of Peace, 1999. Compare the formula in a letter from 1980: “freedom to hold or not to hold a particular faith and to join the corresponding confessional community.”

[18] See John Lamont’s penetrating study.

[19] See my articles here and here, and Ed Feser’s article in First Things online. There will undoubtedly be a thousand more responses, all equally capable of showing the magnitude of the problem Francis has (once again) created for himself and for the entire Church.

[20] First, such a presumption contradicts both the natural moral law and the divine law. Second, even if there were nothing doctrinally problematic in the content of the pertinent motu proprios, the result of a vast increase in easily granted annulments on thin pretexts will certainly redound to the harm of the faithful by weakening the already weak understanding of and commitment to the indissoluble bond of marriage among Catholics, by making it much more probable that some valid marriages will be declared null (thus rubber-stamping adultery and profaning the sacraments), and by lowering the esteem with which all marriages are perceived. For good commentary, see Joseph Shaw here, here, here, and here.

[21] Reverendissimi D. Domini Melchioris Cani Episcopi Canariensis, Ordinis Praedicatorum, & sacrae theologiae professoris, ac primariae cathedrae in Academia Salmanticensi olim praefecti, De locis theologicis libri duodecim (Salamanca: Mathias Gastius, 1563), 197. This is often cited in a paraphrase: “Peter has no need of our lies or flattery. Those who blindly and indiscriminately defend every decision of the Supreme Pontiff are the very ones who do most to undermine the authority of the Holy See – they destroy instead of strengthening its foundations.” (This is how it appears, e.g., in George Weigel, Witness to Hope: The Biography of John Paul II [New York: HarperCollins, 1999], 15.)

[22] St. Robert Bellarmine: “Just as it is licit to resist the Pontiff that aggresses the body, it is also licit to resist the one who aggresses souls or who disturbs civil order, or, above all, who attempts to destroy the Church. I say that it is licit to resist him by not doing what he orders and by preventing his will from being executed; it is not licit, however, to judge, punish, or depose him, since these acts are proper to a superior” (De Romano Pontifice, II.29, cited in Christopher Ferrara and Thomas Woods, The Great Façade, second ed. [Kettering, Ohio: Angelico Press, 2015], 187).

[23] The Liturgical Year, trans. Laurence Shepherd (Great Falls, Mt.: St. Bonaventure Publications, 2000), vol. 4, Septuagesima, 379-380. He is speaking here of opposition to the Nestorian heresy.