During a recent dinner conversation, a Jewish friend asked me, with sincere politeness, if I agreed with the Church’s attempts to “impose its morality” on a pluralistic society when it comes to abortion and other hot-button issues. She, like other American secularists, — I say “other” because, although my friend is Jewish, the Reform denomination to which she belongs has become more or less a wing of American secularism — cannot abide the thought that people of faith can and should bring their religiously-informed moral views to bear in public life. As is heard so often today, “You can’t legislate morality.”

During a recent dinner conversation, a Jewish friend asked me, with sincere politeness, if I agreed with the Church’s attempts to “impose its morality” on a pluralistic society when it comes to abortion and other hot-button issues. She, like other American secularists, — I say “other” because, although my friend is Jewish, the Reform denomination to which she belongs has become more or less a wing of American secularism — cannot abide the thought that people of faith can and should bring their religiously-informed moral views to bear in public life. As is heard so often today, “You can’t legislate morality.”

To say that morality and law shouldn’t mix is frankly silly and flies in the face of everything we know about the history of every system of law since at least the Code of Hammurabi. The truth of the matter, I answered, is that legislation is always based on somebody’s idea of what is right or wrong, just or unjust, fair or unfair. Whether or not the sources of their beliefs are called “religious” is neither here nor there. How are we to describe the civil rights laws of the 1960s, except as the codification of a moral imperative? And what are our various social welfare laws, if not expressions of a corporate responsibility for the poor, the old, and the sick among us? The question, then, is not whether but how we legislate morality.

I expected my friend to seize on the reference to civil rights. She did, showing herself impervious to my argument that opposition to gay “marriage” is not the moral equivalent to white supremacy. Where the language of “choice” and “equality” has been hijacked for infanticide and the destruction of marriage, Catholic moral teachings are bound to be regarded as intolerant and intolerable, especially when they confront the god of Personal Autonomy. But at least I managed to convince her (in the time it took for us to finish our cocktail) that morality can be and frequently is codified in human law, even if we “agree to disagree” over whose morality should hold sway.

Then came the question for which I was less prepared: Why don’t the bishops, or Catholics more generally, seek to outlaw all vice? Why oppose legalized abortion, for instance, and yet not advocate the legal prohibition of contraception, in-vitro fertilization, and other practices which the Church deems fundamentally immoral? (We’ll have another round, please.) The short answer is that not everything that is contrary to the natural or moral law must necessarily be outlawed. Saint Thomas Aquinas, the Common Doctor of the Church, addresses the question, “Whether it belongs to the human law to repress all vices?” (By “vices” he means clear moral evils, not personal foibles.) In the Summa Theologiae, he teaches:

Human laws do not forbid all vices from which the virtuous abstain, but only the more grievous vices from which it is possible for the majority to abstain; and chiefly those that are to the hurt of others, without the prohibition of which human society could not be maintained: thus human law prohibits murder, theft, and suchlike. (ST I-II, q. 96, a. 2)

Elsewhere St. Thomas teaches that human law “is said to permit [permittere] certain things, not as approving of them, but as being unable to direct them” (ST I-II, q. 93, a. 3, ad 3). Note his clarification: by “permit” is meant “tolerate,” not “approve.” The law may justly tolerate some moral evils, even though it cannot justly approve of them or establish a right to commit them.

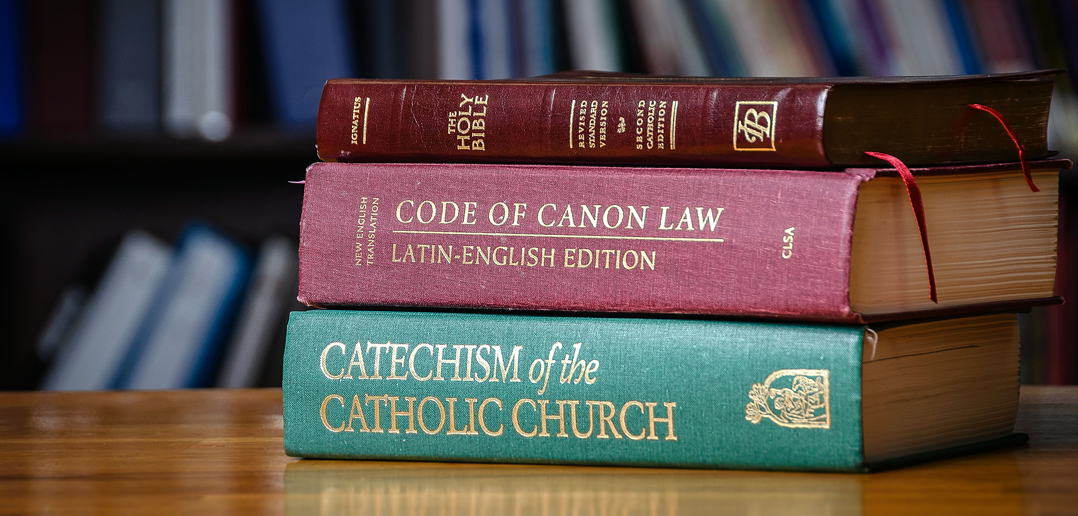

Of course, I didn’t have my copy of the Summa on hand at the time. I simply recalled St. Thomas’ observation that human law prohibits those moral evils that harm others, while tolerating other immoral actions in consideration of circumstantial factors. (Is there anyone who believes we should enact and enforce laws against uncharitable gossiping? Masturbation?)

Any system of human law that fails to prohibit murder, including the intentional killing of human beings in the womb, fails to safeguard what is fundamental to the law itself, namely, the peaceful condition of society. Even if it’s desirable to withhold criminal penalties in certain cases of procured abortion, the mere existence of such a law would be profoundly important. People being the way they are, some, perhaps many, wrongly conclude that if an act isn’t illegal, it isn’t immoral.

At this point, thanks to the waiter, the conversation shifted to our mutual love of oysters. (I told you she’s Reform.)

What triggered this little recollection was my recent re-reading of an article by George Cardinal Pell entitled “Intolerant Tolerance” (First Things, August 2009). In it, he states:

Limits are an inescapable part of human life and society. The only questions are whether they will be the limits of servitude or the limits of freedom, and whether self-love or love of others will predominate.

Food for thought, reflection, and prayer.

You CAN legislate morality. The early 20th Century prohibition on alcohol in the United States resulted in many fewer deaths involving alcohol. But all we hear about is the speakeasy. Secondly, there would be fewer deaths of unborn children via abortion if it remained illegal. Thirdly, there would be fewer adolescents lured into homosexual behavior if such behavior remained illegal. You CAN legislate morality and the Liberals know this.

Clearly law can compel adherence to some moral code. Question is when should it? Jesus appealed to people to understand and voluntarily submit to the moral law because it is for their good. He also gives us free will to disobey. It seems the proper place for civil law is in restricting conduct where one harms another. All else the Church should focus on converting the people to choose to live morally.

The example of prohibition is double-edged. There MAY have been fewer deaths related to alcohol poisoning. There were way more deaths related to smuggling and violence.

IVF and contraception should be outlawed. They were for most of human history. It wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century, in the horrible Griswold vs. Connecticut Supreme Court decision, that contraception ceased being illegal. The bishops no longer speak of the immorality of contraception, let alone fight for it being illegal again. All vice shouldn’t be outlawed, but IVF and contraception should.

The matter has also been put this way: “It is not a question of whether or not morality will be legislated, it is a question of WHOSE morality.”

VERY good article. The kind I like to read the most.