Jacques Fesch was living the American dream. Except he wasn’t living in America. He was living in France. His Belgian-born father was a bank president. The family was wealthy and lived in an exclusive district of Paris. Fancy vacations, private schools, luxury goods. That was his life. “He was living the perfect life!” said his peers.

Except that he wasn’t. His family life was “utterly wretched,” he reported later. “The father bears a heavy weight of responsibility,” said his wife of her father-in-law. They were “frightful parents” said a childhood friend of Jacques. A sensitive boy, he grew up in a negative atmosphere, with no love or respect shown by the parents to each other. Or to the children. His father, an atheist, was full of charm with others, but cynical and harsh with the family, particularly his son, Jacques. His mother was a defeated, depressed woman.

Jacques “absorbed all this into his psyche.” He became an atheist in his teens. Referring to his religious upbringing, he recalled, “It was as though I grew up in a stable.” At the age of seventeen he was expelled from a Jesuit High school. He married at twenty and had an infant daughter. The couple separated after two years of marriage and he then moved back home with his mother. His parents had divorced by this time. Jacques felt like a failure and was overwhelmed by a feeling of lassitude and despair.

But then all this changed: He went on a trip to New Rochelle and glimpsed a sailboat. “That’s it! That will solve everything!” he thought. He now had something to live for! He dreamed of sailing around the Galapagos Islands in that glorious sailboat. What an escape from the misery of his life! The dream became a “horrible obsession.” He could think of nothing else. The only problem was: how to finance such a venture? He approached his father about a loan but was refused.

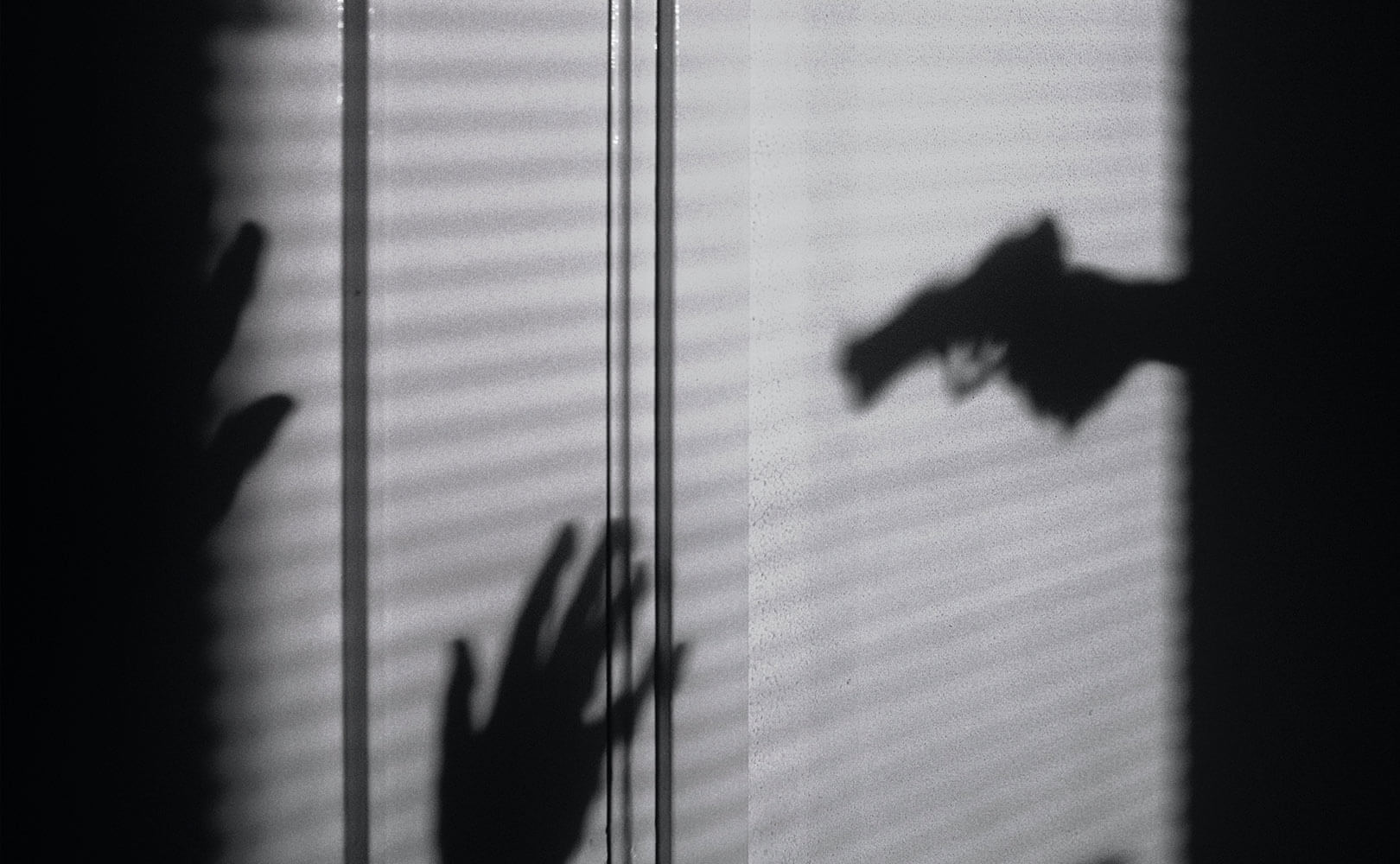

But: He had to get that boat! It would save his life! In his urgent desperation he decided to rob a moneylender who was a friend of his father. The date was Feb. 25, 1954. During the failed robbery attempt and ensuing police chase, he shot and killed a policeman.

After a year in prison, a year of “deep and brutal suffering” the deeply repentant Fesch found his life transformed. On the night of Feb. 28, 1955. He described it in his own words: He met “the One who waits unwearyingly for the wounded and desperate soul—Who is watching for my arrival as I come staggering under the weight of my cross.” Through this mysterious encounter, Fesch became a new man: “Grace had come to me. A great joy flooded my soul!” he exulted.

He described the suddenness of his conversion: “Within the space of a few hours I came into possession of faith with absolute certitude. I believed!” He could not understand how he had ever managed not to believe. His priorities changed instantly: “Now, He is all that matters. A powerful hand has seized me.” He was “amazed and stunned” by the entire experience. “I am living through marvelous hours!” he said. And yet, here he was, a man in his twenties, facing death by guillotine. He understood: “Because of our sins it takes a very strong remedy to restore us to grace.” He pondered: “How many souls have been changed in concentration camps or on battlefields?”

He felt called to a close relationship with the Blessed Virgin. “I pray above all to the Blessed Virgin Mary,” he said. It is to her that he confided all his sorrows. “When I feel alone, I need only take refuge in her. She guards and consoles me like a little child.”

He was also given awareness of the absolute necessity of the Catholic Church for salvation. He wrote regularly to his mother-in-law who was not practicing her faith. He exhorted her: “It is she who distributes all of Christ’s gifts. In rejecting her you deprive yourself of all the helps, benefits and graces which Christ has placed within her.” “Be reconciled with our Holy Mother Church!” he pleaded.

He came to realize the utter seriousness of death. He spoke of his sentence by guillotine: “It is unjust, inhuman, barbaric.” “Executions are horrible,” he said “but the execution of the damned in the next world is far more terrible.”

He said we pay too much attention to things that happen in this world. “It is nothing” he said, except as a preparation for the next world. “All that matters is the desire to love God. He must come first!” Fesch’s great desire was to save souls. That is why he couldn’t help crying “Watch out!” when he saw others “walking a tightrope over a sea of fire. I would like to show them the danger but they are wearing blindfolds.”

Fifteen days before his death he wrote: “Let us not remain blind. Let us be on the watch!” He offered his death for the salvation of souls, particularly for his father who persisted in his atheism.

Five hours before his death (the lawyer had told him that the execution would take place the next day at four in the morning) he wrote: “In five hours I will see Jesus! May the will of God be done in all things! I have confidence in the love of Jesus. I know that he will order his angels to bear me in their hands.” Jacques had been given foreknowledge that he would enter Heaven.

On Oct. 1, 1957, Jacques Fesch was guillotined. He was twenty-seven years old. His last words were, “Holy Virgin, have pity on me!” He was the last person in France to face death by guillotine.

In 1987, the Archbishop of Paris, Jean-Marie Cardinal Lustiger opened a formal inquiry into his possible beatification.

After his death, the Cardinal began hearing reports relating to Fesch’s intercession: healings were taking place, jobs were being found, marriages were being transformed. So many miracles! While he was in prison Fesch wrote hundreds of letters. These prison letters were published in book form, known as Light Upon the Scaffold, and became widely read in France. Hearts were being touched and lives were being changed after reading Fesch’s letters.

Cardinal Lustiger believed that his canonization would give hope to a world that has lost its way. “No one is ever lost in the eyes of God, even if he is condemned by society,” he said.

Jean Duchesne, president of the Paris diocesan commission reviewing Jacques Fesch’s life, agreed. “God still cares for someone who’s been legally sentenced to death and executed. No one is so abandoned and rejected as to be beyond God’s love,” he affirmed.