This month marks 450 years of the Bull Monet Apostolus of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni († 1585), with which, on April 1, 1573, the worthy successor of Pope St. Pius V († 1572) instituted the solemn feast of the Rosary (festum sollemne sub nuncupatione Rosarii), to be celebrated every year on the first Sunday of October.[1]

Following up on the initiative of his predecessor, who had been the soul of the Christian forces’ maritime victory in the Lepanto gulf over the Turkish fleet (October 7, 1571), and the great devotion to the Rosary, which flourished among the faithful, Pope Boncompagni reports that through that triumph “by a great gift of God, all the Christian people had been saved from the jaws of an impious tyrant.” Then the Pope states that “St. Dominic, in order to avert God’s wrath and obtain the help of the Blessed Virgin, instituted this practice so pious that it is called the Rosary or Mary’s Psalter.” That victory, Gregory XIII adds, “must be attributed to the prayers that on that day the Confreres of the Rosary from all over the world offered to God through the mediation of the Blessed Virgin in the processions they then made according to their institute.” Finally, Pope Boncompagni proclaims a solemn feast with a double major office under the name of the Most Holy Rosary for the entire Dominican Order and for all churches that have a chapel or at least their own altar sub invocatione Beatæ Mariæ Virginis a Rosario (under the invocation of Our Lady of the Rosary).

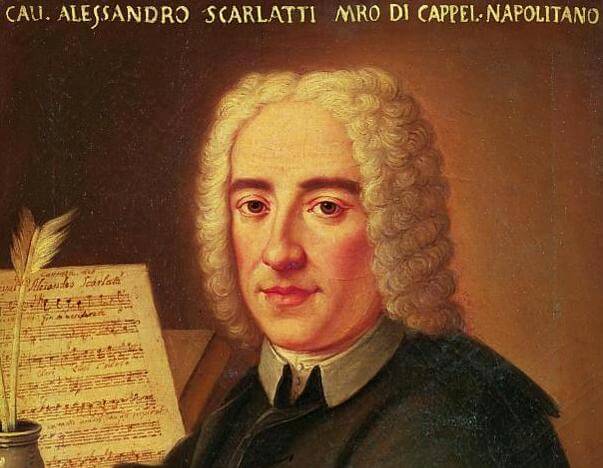

To Our Lady of the Rosary is dedicated Il giardino di rose – La Santissima Vergine del Rosario, an oratorio for five voices and instruments by the Sicilian composer Alessandro Scarlatti († 1725).

This artist was described as musices instaurator maximus (the supreme restorer of music) and optimatibus regibusque apprime carus (most dear to aristocrats and kings), as attests the memorial tablet above his tomb, in the chapel of St. Cecilia at Santa Maria di Montesanto in Naples, dictated by Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni († 1740). On December 31, 1703, it was precisely this cardinal, great admirer of Scarlatti, who wanted him in the Basilica of Saint Mary Major in Rome, of which he was Archpriest, first as coadjutor and substitute for the director of music, Antonio Foggia († 1707), frail in health, then as the latter’s successor, from June 5, 1707.

Composed in 1707, on commission from the Marquis Francesco Maria Marescotti Ruspoli († 1731), who is perhaps the libretto’s author, Il giardino di rose was performed on April 24 of the same year, Easter Sunday, in the great hall of Palazzo Bonelli (now Valentini) in Rome, since 1705 the Marquis’ residence. The chronicles speak of it as “a beautiful oratorio […] made in the house of the Marquis Ruspoli with a large number of nobles.”[2]

We have before us one by the Sicilian musician’s best efforts, “an exemplary work, a model of European value”, as says Saverio Franchi († 2014), who in 2006 produced the first critical edition, in which this article’s author collaborated.[3] Even a twenty-two-year old George Frideric Handel († 1759), a guest of the Marquis Ruspoli between 1707 and 1709, had to compete with Alessandro Scarlatti, especially for the composition of his oratorio La resurrezione (The Resurrection), which, conducted by Arcangelo Corelli († 1713), would be performed on Easter Sunday of the year after Il giardino di Rose, still in Palazzo Bonelli, still commissioned by the Marquis Ruspoli.

Scarlatti’s oratorio, divided into two parts, is conceived for five characters (Carità and Speranza, sopranos; Penitenza, alto; Religione, tenor and Borea, bass), a flute, a bass flute, two oboes, a bassoon, two trumpets, strings and basso continuo. As an allegory, the location in which the five interlocutors appear is a garden of roses: the thorns, which are never missing among the roses, represent the penance that one must necessarily undergo in order to recreate oneself in the garden; the storms, caused by the “crude north wind,” are the threats of Lucifer under the name of Boreas, the icy wind coming the north; the roses symbolize the Hail Marys of the rosary, like a

garland around the most beautiful, the purest, the holiest of all women, the blessed, Virgin and mother, with a hundred unique titles: the new Eve, the seat of Wisdom, the Immaculate Conception, Our Lady of Sorrows, the Assumption, the Queen of Heaven, the Mother of God Incarnate, the Mother of the Church… An endless litany.[4]

In particular, we find, “among its characters, Religion in a tenor voice with explicit allusion to Pope Clement XI,” then reigning.[5]

A Symphony in D major of almost five minutes, in tripartite form (Adagio-Presto, Largo e piano, Allegro), precedes the oratorio.

Then a series of dry recitatives (i.e. accompanied only by harpsichord) and arias, almost all in the Scarlatti style (i.e. in the form with the da capo written in full), with the inclusion of a few duets, unwind. Some of the 55 numbers of this extended musical drama go beyond the rule: the small “storm” at the end of the first part; the aria Fra gl’ardori di questi fiori, which is bipartite; the intervention of Borea, at the beginning of the second part, O del profondo e formidabil regno, written in that intermediate form between recitative and aria which in music is called arioso; and the piece for four voices, at the end of the oratorio, Con la speme, written in that polyphonic form known in music as concertato.

Maria Isabella Cesi († 1753), wife of the Marquis Ruspoli and maternal niece of Pope Innocent XIII († 1724), was “very devoted to Our Lady of the Rosary and also a lover of music.”[6] May Scarlatti’s music still induce us too to turn with confidence, in our needs, to her, who shines forth, “until the day of the Lord shall come, as a sign of sure hope and solace.”[7]

[1] Cf. Magnum Bullarium Romanum, Tomus II, Luxembourg 1742, p. 399.

[2] G. Staffieri, Colligite fragmenta, Lucca 1990, p. 172. Our translation.

[3] S. Franchi, Introductory note to A. Scarlatti, Il giardino di rose, Rome 2006, p. IX.

[4] Paul VI, Angelus, October 1, 1972. Our translation.

[5] S. Franchi, Annali della stampa musicale romana dei secoli XVI-XVIII, Vol. 1, Rome 2006, p. 487. Our translation.

[6] S. Franchi, Introductory note cit., p. XII.

[7] Second Vatican Council, Lumen gentium, 68.