The Irish Fight for the Latin Mass, pt. III

Pt. I: Rise of the Anglican Regime

Pt. II: The Glorious Dublin Martyrs

Pt. III: The Pirate Queen and the Irish Fighting Spirit

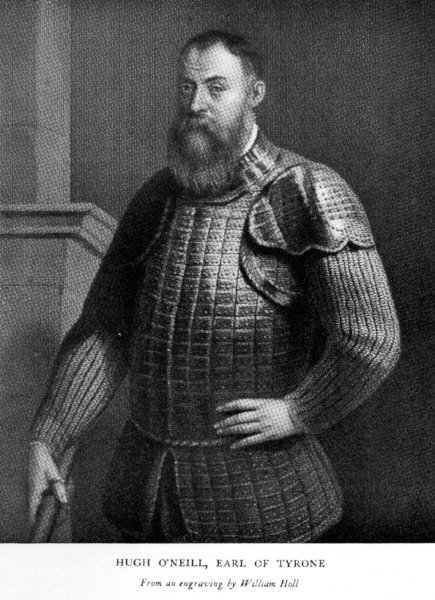

The Rise of Ó Neill

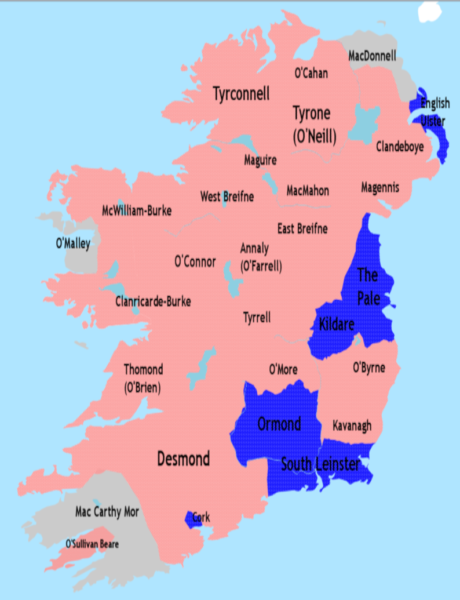

With Connacht pacified, the Crown turned to the most daunting task yet. The northern province of Ulster was the most Catholic and Gaelic in all of Ireland. Unlike the other Gaelic fiefdoms, Ulster had remained largely united under its traditional Princes, the great Ó Neill dynasty. With strong clan links to the Scottish Highlands, and deep trading links to Spain, Ulster was militarily and commercially robust, confident in its ancient identity and well hardened to the wages of war.

Initially, it seemed as if Ulster would capitulate without a fight. The Ó Neill clan, led by Hugh O’Neill, had nominally submitted to the Queen, and, as far as the government was aware, actively aided the Crown in the suppression of the lesser northern lordships. When a vast shipment of lead arrived in Ireland bound for Ó Neill, they trusted his explanation that it was to repair the roof of his castle at Dungannon. It was to be a costly mistake.

In 1595, Ó Neill turned on the English and reversed their advances in the north through a series of crippling defeats. His lightning campaign changed utterly the face of the war. He sent riders after his victories to herald the news; the English army in Ulster had been defeated. Immediately, in a great wave of sword and flame, the subdued Lords and Peasants of Connacht and Munster rose up once again. Castle after castle fell until virtually the entire island outside of the Pale bent its knee to Ó Neill.

Ó Neill seemed to be on the verge of reclaiming his ancestral birthright. His dynasty had, from the age of Saint Patrick till 1002, sat on the ancient throne of the High Kings of Ireland. The Catholic Norman lords of the Pale stood as the one great barrier between him and the city of Dublin. If they joined him, the city would certainly fall, and English power in Ireland would finally be at its end.

At the height of his power, he wrote a declaration and had it disseminated throughout the Pale. In it, he makes his cause clear to the hesitant Palesmen, solemnly vowing to “employ myself to the utmost of my power for the extirpation of heresy, the planting of the Catholic religion and the delivery of our country.” It was a plan that was neatly summed up in his motto “Pro Fide et Patria,” for faith and fatherland.

The Government panicked at this declaration, fearing that the Catholic lords would join him, and immediately enlisted the premier lords and scholars of the Pale to write a rebuttal. Lord Devlin, responded that Catholics were enjoined to suffer evil monarchs as well as good and that the loyalty they owed to the Queen could not be abandoned since their oaths could not be dispensed with. She was rightful Queen, heretic or not, she demanded their loyalty. The Pale would not rise.

The Anglican Counter-Attack

In 1599, Lord Essex arrived in Ireland with 18,000 men, the largest English army ever assembled. The Queen’s favourite and hero of the infamous raid on Cadiz that destroyed the Spanish navy, Essex had one goal; to defeat the Irish and bring the country back into line.

Marching northwest to retake Sligo from the Irish and avail of its port for the future campaign into Ulster, the army marched along the ‘Bóthar Buídhe’ through the Curlew Mountains. On the Feast of the Assumption, the army was attacked and defeated by Ó Donnell of Tyrconnell, forcing a retreat. The remaining English forces never recovered. Besieged in their castles, countless men perished from disease and starvation. By the end of the year, Essex had been recalled to London and executed.

The new Lord Deputy was not a man of tender conscience. Mountjoy learned from the devastation that had brought Munster to surrender almost twenty years before, and began a similar process in Ulster. Using amphibious raids from the sea, he rampaged through the north with a single objective; utter destruction. He did not seek to establish garrisons, or take castles, or engage in battle, his only target was the farmland of the north.

The raids on Ulster intensified in May and June of 1600. His first target was the hay crop and the fattening cattle on the summer pastures. No quarter was to be given to the villagers. At the end of the summer, he targeted with devastating effect, the grain harvests, burning the fields in the midst of the summer heat. The mills and farms in particular were to be destroyed. By the winter, the intended effect took hold, and Ulster suffered crippling famine.

By 1601, the Famine was seriously hampering the Irish and Ó Neill was weakening. The population began to lose faith in him as the starvation of their families gathered pace. The demands of the army likewise put even greater burden on the starving population. Although he managed to defeat an English invasion of the north at the Battle of the Moyry Pass, the collapsing morale of the army was making the further continuation of the war unlikely.

And then, in October 1601, a messenger arrived at Ó Neill’s court. The long-awaited Spanish had finally arrived.

The Spanish Reinforcements

This joyous news was, however, not without its bite. Due to stormy weather, the Spanish had not landed in Ó Neill’s stronghold of the north, as had been planned, but at Kinsale, on the far southern coast of Ireland. With the winter closing in and the land in the grip of famine, he called the army out for this great battle.

In Dublin, the news of a Spanish invasion sent the administration into chaos. Dispatches from London had warned that the Crown was on the verge of bankruptcy and now the depleted forces had to contend with a Spanish army. Mountjoy settled the panic and levied all Crown forces available in the Pale and force marched south to Kinsale, arriving before the town and set to besieging the Spanish inside the walls with a constant barrage of artillery.

Ó Neill, hearing that the Spanish were trapped in the town, immediately set out from Ulster with the army. The winter was hard that year and the chroniclers tell us of heavy snows and rains that bedogged the Irish on their 300 mile march south. Desperate to reach Kinsale, Ó Neill allowed no lengthy rests for the army, save one.

In December, the army took a detour and arrived at the Abbey of the Holy Cross. This venerable monastery possesses one of the great relics of Ireland, a fragment of the True Cross sent to King Dónal by Pope Urban III. Ó Donnell, whose arms displayed the Cross lifted upright, and whose dynastic motto was “In hoc signo vinces” is noted to have payed special reverence for the relic. Their pilgrimage would not be without its blessings. Before leaving the Abbey, news reached the Irish of a secret supply caravan making its way to the English at Kinsale. Sending his cavalry, Ó Neill seized the supply train, cutting off Mountjoy from badly needed food and ammunition.

The English army began to starve, and in the fetid conditions of the camp, as well as the bitter winter weather, disease and desertion began to take hold. Soon after, Mountjoy beheld the Irish army take hold of the hills behind him. Sandwiched now between the Irish on the hills, and the Spanish in the town, and with the last English forces of Ireland gathered in the squalor and disease of the camp, Mountjoy’s mind must have turned to the Pale, now virtually defenceless. He is recorded as having said “the Kingdom is lost.”

In the early hours of Christmas Eve 1601, a traitor from Ó Neill’s camp came before him, and warned that at dawn, the Irish would launch their attack. It was the vital lifeline Mountjoy needed for he knew well that the fate of the kingdom would be decided at the walls of Kinsale.

As the sun rose on that Christmas Eve, the Irish did not find the English unprepared. Volley after volley of assault was attempted on their positions, to no avail. The English cavalry, reputed the finest in Europe, began their charge. Ó Donnell led his men into the boggy ground of a valley hoping that the horses would become stuck in the mire, but the frost of the night before left the ground hard as stone. The cavalry smashed into Ó Donnell’s battalions and scythed them down. Ó Neill, seeing his ally breaking in the valley, charged his men from the hills to assist him. The English, seeing their chance, took the hill, and charged down into the valley.

The Irish were utterly routed and fled northwards to Ulster in complete defeat. The Spaniards abandoned the town of Kinsale and returned to their ships, sailing out of Kinsale Harbour with the news that the great Catholic army had been broken. On their way, they met a new fleet of Spanish ships on its way to Ireland with fresh reinforcements for the Catholic cause. Both fleets returned to Spain, never to assist Ireland again.

The Fall of Ulster

With Ó Neill’s army in tatters and his people devastated by years of war and famine, the English launched a coordinated invasion of Ulster in the spring. This time, they met only minimal resistance. Mountjoy took Ó Neill’s castle at Dungannon and burned it. He then proceeded to Tulloghogue to the great stone of the Ó Neills, the spot where the dynasty had inaugurated all of its princes from time immemorial, and had the stone smashed into pieces. The monasteries, which until now had remained untouched, were sacked, their religious martyred.

At Coleraine, the venerated image of Our Lady was burned alongside other celebrated images of pilgrimage in Ulster. Father MacFerge, the prior and the twenty four brothers of the Dominican friary in the town were slain. At Derry, the celebrated monastery of Saint Columba, thirty two of the monks were killed in an orgy of bloodletting. The bishop of Derry was hung and disembowelled.

“The Flight of the Earls”

With the whole of the island now finally under Crown authority, a more brutal phase in the persecutions could begin. One of the more horrific moments of these days occurred at Scattery Island in the River Shannon. A group of forty-nine monks who had agreed to leave the country for Catholic Europe, were weighed down with chains and thrown overboard to drown.

Father Bernard Moriarty, the vicar general of Dublin faced sustained torture by soldiers. Eventually, they broke his thigh bones and interred him in the dungeons of Dublin Castle where he died in the squalor and darkness that once housed Margaret Ball.

I include the details of these martyrs not because they are particularly special. In any study of this period, the lists of martyrs that are casually recorded by the authorities reads something like an accounts ledger, an almost endless roll of bloodshed and torture. When one reads these lists certain names stick out, certain places stick out, but in reality, there are few places on this island that were not watered in those years by martyred blood.

In 1607, the flower of the Gaelic aristocracy gathered at the little fishing village of Rathmullen in County Donegal. The great dynasties that had ruled Ireland from ancient times were all present, alongside clergy, scholars, bards and scribes. Among them was Ó Neill, but Ó Donnell was not present. He had fled Ireland for Spain immediately after Kinsale to raise another Spanish army for the Catholic cause, only to be poisoned by an English agent. There would be no more assistance from the continent.

Great crowds of farmers and servants also gathered to witness this seminal moment in Irish history. When the winds permitted, the jewel of Gaelic Ireland boarded a ship in the harbour and sailed into exile. The old Gaelic nobility was gone. The assembled crowds could not have been ignorant of what that moment meant, for they had just witnessed the death of a civilization that had been ancient when Julius Caeser first climbed the steps of the Roman Senate. In the end, it died, not with the clamour and clash of war, but with the dissappearence of sails over the horizon.

The years of war were now over, the years of blood were about to begin.

To be continued…

Photo by Leighton Smith on Unsplash