Above: Doonagore Castle (“fort of the goats”), Doolin, Co. Clare, Ireland. Photo by Jesse Gardner on Unsplash

In the English speaking world, the story of Catholicism during and after the Reformation is dominated by the experience of England. The sad tale of an ancient Catholic kingdom subjected to the yoke of Protestantism, of a systematic persecution of the Faith, and the making of martyrs. Who, can I ask, has not heard of St. Thomas More, or St. John Fisher, the scandal of Henry VIII and his six wives, the Pilgrimage of Grace, Mary, the Queen of Scots, the Gunpowder Plot and Treason?

The history of English Catholicism is well known and deservedly beloved.

Yet, to the west of Britain, there lies another island whose story is unique for the period. Ireland is peculiar in many ways, but is particularly strange for being the only country in northern Europe to have successfully resisted the Reformation.[1]

That story is largely unknown. For most, it is simply a tale of Irish national resistance against the dominance of her larger and more powerful neighbour. As one historian put it, “had the English remained Catholics, the Irish would have adopted devout Protestantism out of spite,” but such an assumption is gravely mistaken.

The truth is that Irish nationhood was born in the crucible of the Reformation, through a union of two peoples, not by shared birth on this Atlantic battered island, but through adherence to a common faith. Certainly, the politics of identity and ethnicity played its part, and at points in this story, it can be hard to see where Irishness ends and Catholicism begins.

Nonetheless, in the epic I am about to tell, you will see that it was the blood of martyrs and an absolute – some might say “rigid” – determination to preserve the faith of their fathers that birthed a nation.

It was not resistance to preserve nationhood that maintained the Catholic faith in Ireland, rather it was determination to live and die in their faith that forged Irishness.

It is a story in which you will meet golden heroes, martyrs whose suffering and constancy rivalled that of the early Christians, and a people whose simple refusal to sacrifice their faith could not be moved despite the best efforts of a government over three hundred years. It is also a story, predictably, with its villains, as all such stories must have. Some of these villains will surprise you, but it is precisely for the example of our saints and sinners that this story should be better known.

In these days, when we have our own struggle to accomplish, let the story of the Irish Church over these centuries serve as an inspiration, and an example, to our brothers and sisters in every corner of the globe.

Let us begin.

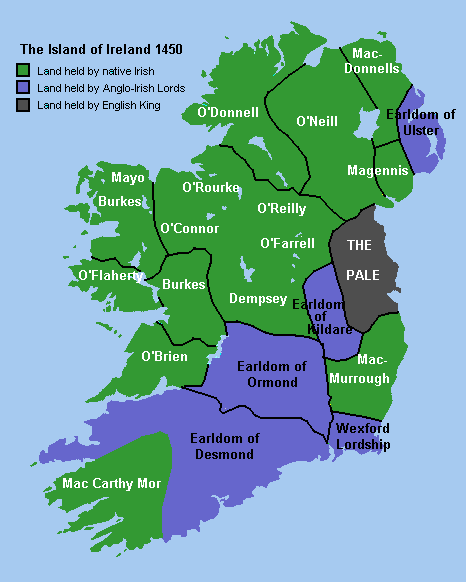

Divided Ireland

Sixteenth Century Ireland was a land of two nations. Most of the country remained under the sway of her traditional Gaelic lords, the ancient dynasties that traced their rule back into the depths of pre-history. They ruled as their fathers had, in an intricate web of clan ties and allegiances over a patchwork of fiefdoms. This was unconquered Ireland, ‘Hibernia Invicta’ as they described it. Lauded by their bards and harpists, the Gaelic lords ruled from castles that formed the heart of rural communities and scattered villages. They were bound by the ancient Brehon Laws, codified by the High Kings of old, but, more importantly, by the limited resources their almost parochial kingdoms could provide.

However, in a small, and shrinking, enclave on the east coast, there was another Ireland. These lands, centred on the city of Dublin, had fallen to the Norman invasion in 1171 and remained firmly within the bounds of the English crown. This was a very different world, inhabited by English colonists who lived lives in a manner almost identical to their homeland. A centralised bureaucracy administered the King’s justice, they wore English fashion, spoke the English language and prided themselves in the purity of their cultural ties to the motherland. Indeed, so conservative were they in preserving their English identity that they were regarded by English mainlanders as cultural curios, a relic of an England that had long since passed away.

This cultural confidence of the inhabitants of the English Pale belied the insecurity of their foothold on the island. Less than ten miles from the city gate lay the Gaelic lordship of Cuala that bore down on them from the mountains. Once a year, they marched out in a magnificent procession and blew trumpets towards the hills in a show of defiant resistance, before promptly returning behind the city walls in a not-so-defiant show of realism. Nonetheless, provisioned from the sea and their meagre hinterland, and guarded by the great noble houses of Fitzgerald, Fitzpatrick, Burke and Butler, their tenuous foothold would endure.

The Church Made Ireland

On this island of two nations, there was one unifying force that could call on the loyalty of Celt and Saxon alike; the Church. Seamlessly, the network of parish churches, friaries, abbeys, and cathedrals ensured that no one was more than three miles from a church anywhere on the island and although the two peoples lived for the most part separately, at the great pilgrim shrines they routinely found themselves beside each other in prayer, in the religious houses both nations lived under one roof. For all their incessant squabbling and warfare, both found shelter under the indomitable skirts of Holy Mother Church.

It would be wrong however to look upon this land as a Catholic idyll. The Irish Church in the late Middle Ages reached a level of depravity seldom matched in its long history. It was, according to a Papal legate of the time, the “most rotten branch in all of Christendom,” I shall not go into further detail here. In light of this, the Irish Church seemed to be a ready victim for the storm that was about to engulf it, that the whole decayed edifice would be swept away in consequence of its own corruption and refusal to reform. Yet, as is often said, dung grows the best roses.

The First Salvo of the Anglican Regime

Initially, the progress of the Reformation seemed as though it would pass as smoothly in Ireland as it had in England. The bishops gave little resistance to the passage of the Act of Supremacy in the Irish Parliament, and it passed in the first session. However, the episcopate soon encountered a complete unwillingness of the clergy to obey the injunctions such as it rendered progress impossible. George Browne, the Henrican Archbishop of Dublin, found opposition in the parishes so universal that he was unable to force them to even omit the prayers for the Pope in the Mass. The Chancellor of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, Father John Travers, wrote a treatise in response to the Act entitled “On the Authority of the Roman Pontiff,” for which he was martyred in 1537.

The dissolution of the Irish Monasteries was limited by the reach of the Crown. The religious houses of the Pale had been dissolved without much resistance, but beyond the Pale, London may as well have been the moon for all the local lords regarded the Crown’s writ. In the Gaelic interior, the monasteries continued uninterrupted, with some even commencing extension projects. The government responded by launching raids into the Gaelic lordships where the looting and dissolving of the monasteries became prime targets.

Within the Pale, the authorities had so far resisted any major suppression of the Catholic faith within the parishes. However, when the news of the slow pace of reform reached the King, he sent an edict to Browne demanding the suppression of the cult of relics and saints. Dutifully, the archbishop took the relics of Christ Church Cathedral, including the staff of Saint Patrick, the Speaking Cross, and the miraculous image of Our Lady of Trim, and burnt them in the high street of the city.

This destruction however was not as complete as one might assume. The Heart of St. Lawrence Ó Toole, a prized relic of Christ Church Cathedral, was unharmed and survives to this day. Indeed, in subsequent accounts of the latter years of Henry’s reign, it is clear that Browne was unable to dislodge any of the major shrines in his own Cathedral. The saints would smile down undefaced and complete with their vigil lamps and candles until the reforms of the boy king, Edward. Nor was the problem confined to Dublin. In his visits to the towns of Leinster, Browne wrote despairingly to London that “the churches everywhere are yet filled with images and relics, and I dare not touch them, for fear of the ire of the ignorant populace.”

[1] That is, if we count Poland as Eastern Europe.