Above: Rockfleet Castle. The likely site of Queen Grace O’Malley’s death.

The Irish Fight for the Latin Mass, pt. III

Pt. I: Rise of the Anglican Regime

Pt. II: The Glorious Dublin Martyrs

The wars of conquest in the Gaelic interior continued unabated, and throughout, there were martyrs made. The accounts of the time tell us of a man beaten to death with the altar stones he was trying to save, of lines of friars hung by their cinctures and the campaign of terror inflicted on the rural peasantry. Unable to quell the Gaelic lords by conventional means, the Crown forces resorted to a policy of scorched earth to devastating effect, especially in Munster.

Not even Edmund Spenser, a resolute Protestant and loyal official of the Crown, could contain his pity when he traveled through the devastated countryside and saw the transformation wrought on one of the richest Gaelic states and its people;

Out of every corner of the woods and glens they came creeping forth upon their hands, for their legs could not bear them; they looked anatomies of death, they spoke like ghosts crying out of their graves; they did eat of the carrions, happy where they could find them, yea, and one another soon after, in so much as the very carcasses they spared not to scrape out of their graves; and if they found a plot of water-cresses or shamrocks, there they flocked as to a feast for the time, yet not able long to continue therewithal; that in a short space there were none almost left, and a most populous and plentiful country was suddenly left void of man or beast.

In the campaign, the Bishops of Meath, Emly, Cork and Ross gained the martyr’s crown, alongside countless religious and clergy throughout the province. The devastation was so complete that one chronicler described that there was not a church roof still intact in all of Munster when the province was finally subdued. In the charred ruins of the Catholic patrimony, it seemed to the authorities as if now, resistance to the Reformation was finally broken.

It was a seminal moment in the story of the Irish Church.

The new Bishop of Cork, Dermot Creagh, finally brought to an end the two-faced policy of the Irish clergy under Crown Authority. Under his leadership, there was a mass defection of the clergy out of the official parishes of the Anglican Regime. The old policy of nominal adherence to the State Church whilst preserving the Catholic faith finally gave way and a new parallel Catholic parochial structure was established.

He directed the Irish colleges in Catholic Europe to send their priests home, and they arrived in such numbers that the authorities complained bitterly of “swarms of seminary priests” arriving in the country to such an extent that the policy of repression and execution was proving utterly useless since “every city, town and province is so plentifully replenished by them.”

Their bravery was such that even Edmund Spenser was deeply impressed by newly returned clerics who arrived knowing the “peril of death awaits them and no reward or riches are to be found, save only to draw the people unto the Church of Rome.” The Gaelic poets praised them, likening the black clad clerics to the barn swallows who had returned to their nests from across the seas at harvest time.

The friars too responded, and set out across the country, “in bands of ten to twenty, tramping the full breadth of the kingdom” preaching and administering the Sacraments, gaining the palm of martyr’s victory in scores. By 1590, the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin complained that the friars were operating throughout the Pale, noting especially one Father Tadhg Ó Sullivan, who was “preaching from house to house” in every village and street, including the bishop’s own.

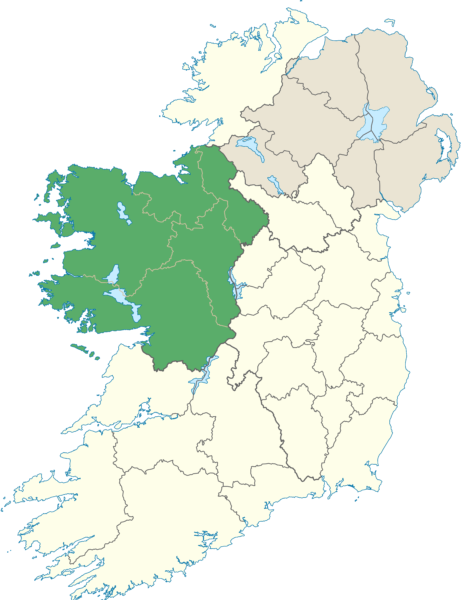

Connacht

With the subjugation of the East and South of Ireland, the Crown turned its attention to the wilds of Connacht in the west. With its mountainous terrain and Atlantic battered coastline, the Lords of Connacht were long beyond the reach of the English authorities. More worryingly for the State, the western Lords had strong commercial links with Spain and Portugal, and though the western coast was largely unchartered by English captains, it was well known to Spanish ships.

The State engaged in a process of carrot and stick with the western lords. On one hand, offering a recognition of their lands and titles if they submitted, on the other, threatening complete destruction if they resisted. Throughout, they engaged in devastating raids into Connacht, and, naturally, the Church would bear the brunt of their rage. Just as in Munster, the Church in Connacht would be brought to destruction at the hands of the Protestant authorities. A vivid picture of the scale of destruction is left to us from a Spanish shipwreck survivor, Francisco de Cuellar:

At the dawn of day I began to walk, little by little, searching for a monastery, that I might recover in it as best I could, which I arrived at with much trouble and toil. I found it deserted, and the church and images of the saints burned and completely ruined, and twelve hanging within the church by the act of the Lutheran English. All the monks had fled to the woods for fear of the enemies, who would have sacrificed them as well if they had caught them, as they were accustomed to do, leaving neither place of worship nor hermitage standing; for they had demolished them all, and made them drinking places for cattle and swine.

One by one, the Lords of Connacht fell to the English or submitted, even the great Ó Connor dynasty, descendants of the last royal house of Ireland, so that from the river Shannon to the sea, the whole province seemed to be on the verge of capitulation. Yet, in the far west, the English met a lady who would halt their advance utterly.

The Pirate Queen

From the wild Atlantic coast of Mayo, where the sea sprayed the walls of her castle, the English met with Gráinne Ó Malley, the famous ‘Pirate Queen of the Western Sea.’ From her base at Clare Island, she controlled a string of castles on her family’s ancestral lands and beyond, up and down the western coast. She had, at her command, a formidable fleet of galleys which she used to halt any advance of the English navy, and to launch raids against Crown possessions along the coast. So unassailable was she that Elizabeth’s own ships had to pay a tax to her or face annihilation.

In the eyes of the English, she was a wildly dangerous woman, the “nurse and mother to all rebellions in Connacht these forty years.” Determined to bring her to submission or destruction, a large English army was assembled at Galway and invaded her lands. Ó Malley annihilated them and sent the commander back to “his Tudor Pope” in disgrace. The crown eventually forced her to negotiate after her son had been captured by privateers. Still, while she lived, the State could only lightly enforce its will on her fiefdom, so conscious were they of her dangerous potential.

Still, for all of Gráinne’s prowess, she was powerless to protect her bishop, Blessed Patrick Ó Hely and his secretary, a Franciscan friar called Blessed Conn Ó Rourke. The pair were betrayed after being assured hospitality by a noblewoman. The saintly bishop was assured power and position if he would embrace Anglicanism, but he would not budge. The pair were brutally tortured and hung by Crown forces, triumphing over the fallen angels and gaining a glorious crown in eternal life.