Editor’s note: this is part of the postliberal conversation at OnePeterFive, in which we discuss and debate how to rebuild Christendom against the Liberal disorder. If you would like to add a submission to this conversation, please email us at editor [at] onepeterfive.com.

Integralism is care for the common good…

In the United States, the particular sin of the conservatism is to endorse wholeheartedly the myth of “rugged individualism.” Conservatives make idols of the virtues of self-reliance, independence, and the rights of the individual. While these are fine to a certain extent, they cannot be ends in themselves. Man was made to be, as Aristotle says, a “political animal.” He is meant to live in a structured, ordered society, where each has a role to play and a duty to fulfill. This idea, understood even in pagan times, finds its most beautiful exposition in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, where he speaks of many parts, but one body. Just as a leg or an eye could not survive on its own, so too we humans make war against our natures when we claim the ability or desirability of life totally in greater or lesser isolation from and in passivity to others.[1] Integralism calls us to be mindful of our obligations to friend, neighbor, and country. In our society, putting the integralist vision of the common good into practice would have its most pronounced effects in the economic sphere and would mean first and foremost the demolition of capitalism as we know it. It has never been Church teaching that man has an absolute right to his money or even his property; rather, man holds in trust all that he has for the greater glory of God and the help and succor of neighbor. His possessions are only his by right insofar as he seeks to use them to build the kingdom of God on earth. Money and all forms of wealth must be used for our own salvation and for the salvation of others, and cannot have as a goal simply the creation of more money. This is why integralists condemn virtually all forms of stock market investment, for example.

Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Rerum Novarum gives perhaps the finest summary of the Church’s (and the integralist’s) stance on the hoarding of wealth, to the detriment of the common good, that has ever been written (paragraph 23):

“Therefore, those whom fortune favors are warned that riches do not bring freedom from sorrow and are of no avail for eternal happiness, but rather are obstacles; that the rich should tremble at the threatenings of Jesus Christ—threatenings so unwonted in the mouth of our Lord—and that a most strict account must be given to the Supreme Judge for all we possess. The chief and most excellent rule for the right use of money… rests on the principle that it is one thing to have a right to the possession of money and another to have a right to use money as one wills…[quoting Thomas Aquinas] “Man should not consider his material possessions as his own, but as common to all, so as to share them without hesitation when others are in need.” [emphasis added]

…but not collectivism or authoritarianism.

Enough has been said in condemnation of socialism and communism, including in many encyclicals, that a repetition of the Church’s perennial teaching on these evil and perverted systems is unnecessary. Similarly, the Church’s condemnation of extreme fascism (see in particular Pius XI’s Mit Brennender Sorge) and race-based nationalism holds forever true. Opponents of integralism must cease the straw man attacks (especially from fellow Catholics!) which calumniate us as socialist or fascist. In a modern world once again tempted to seek salvation in the worship of class, race, or the nation, the integralist shows that Christ alone must be the focus of our worship. In Christ there is no Jew or Gentile, no rich or poor. We must resist the temptation to seek earthly messiahs or utopias and bear in mind that “there is no other name under heaven given to men, whereby we must be saved” but that of Jesus Christ (Acts 4:12).

A note on practicality

At this point, the otherwise well-meaning traditional Catholic is quick to play the skeptic. “Sure, this is all well and good, but it’s never going to happen, so why bother?” Immediately, poisoned by a horizontal and pessimistic Liberalism as he is, the modern Catholic dismisses integralism as not practical, meaning it is not likely to be permitted by the global Liberal regime without a fight to the death. The integralist fully accepts this definition of impractical and relishes it, for it is in the struggle against the powers that be that the Church has always had her proudest moments. Was it practical for twelve mostly uneducated provincials, a few women, and their hangers-on to bring down the most powerful empire ever known to man, to convert its emperor, overturn its temples, and use its rotting carcass to spread a radically new faith to every corner of the world? Was it practical for St. Athanasius to press on in the struggle against Arianism when something like eighty percent of the world’s bishops had gone over to heresy? For that matter, was it practical for small, huddled, and isolated groups of traditionalist Catholics, banished to Una Voce or the SSPX, to hope against hope and dare against the odds to keep alive the dying embers of the Mass of Ages, their sacred patrimony? We cannot forget fundamentals: with God, nothing is impossible. And God will not brook talk of practicality. Have you not read that you must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect? What is practical about that?

Nevertheless, the task is not so daunting as it may seem, for it has the virtue of having succeeded before. Integralism is merely a description of what was historically the default political system of Christendom. It thrived for centuries in the Middle Ages, and although the evils of Protestantism and Masonry have not ceased from that day to this to crush it, it has never fully been suppressed. It has even resurfaced from time to time.[2] Ecuador under President Gabriel Garcia Moreno, the Habsburg Empire under Blessed Emperor Charles, and other examples rea dily present themselves. One must admit that the task is made harder in an era when churchmen and prelates can hardly be relied on to play the role assigned to them in an integralist state, but their sins do not excuse our inaction. We must work to build integralism from the ground up, wherever we live and whatever is our state of life. This will take as many forms as there are Catholics. We may dwell on the words of John the Baptist in Luke 3, where he shows that all are called to sanctify their particular station in life and use their means to build the kingdom of God. Living an integrally Catholic life, together in community with other integral Catholics—this is how we build integralism, practically.

dily present themselves. One must admit that the task is made harder in an era when churchmen and prelates can hardly be relied on to play the role assigned to them in an integralist state, but their sins do not excuse our inaction. We must work to build integralism from the ground up, wherever we live and whatever is our state of life. This will take as many forms as there are Catholics. We may dwell on the words of John the Baptist in Luke 3, where he shows that all are called to sanctify their particular station in life and use their means to build the kingdom of God. Living an integrally Catholic life, together in community with other integral Catholics—this is how we build integralism, practically.

For further study: the leading lights of contemporary integralism. Note: not all of these thinkers have used or would use the term “integralist” to describe their philosophy, but in this author’s opinion, their writings are admirable manifestations of integralist thought.

- Pater Edmund Waldstein

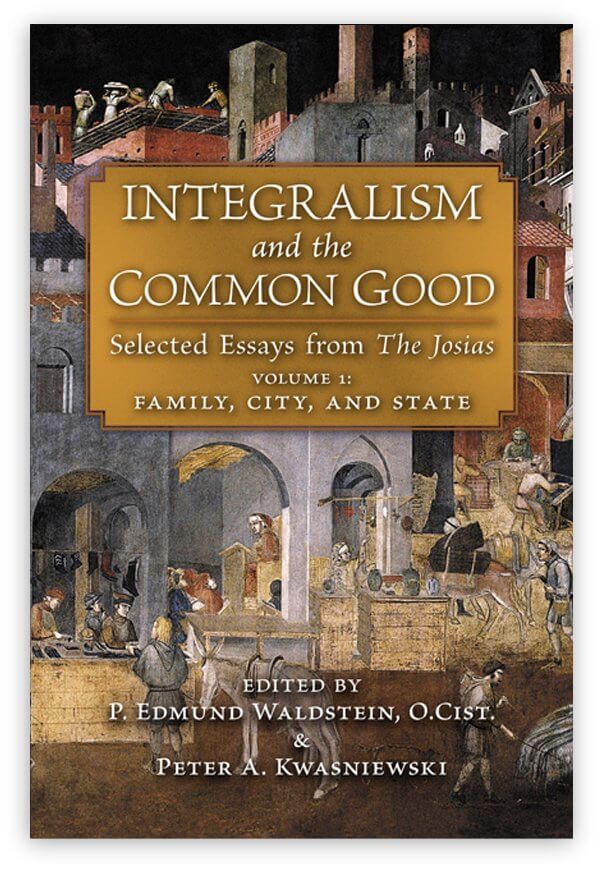

- Integralism and the Common Good

- See also his many articles on The Josias (thejosias.com)

- D. C. Schindler

- Andrew Willard Jones

- Marc Barnes and Jacob Imam

- See their many articles and excellent podcast series at New Polity (newpolity.com)

- Fr. Thomas Crean and Alan Fimister

- Christopher Ferrara

- Patrick Deneen

- Charles Coulombe

- John Médaille

- Brian McCall

- Thomas Storck

- Ryszard Legutko

Photo by Richard Clark on Unsplash

Links in this article earn affiliate income for OnePeterFive.

[1] Although it would appear on the surface that monasticism must thus be condemned, a closer examination reveals that the religious, whether hermitic or living in community, devotes his entire life to prayer for the Church, thus uniting him to his fellow man more closely than are most laypeople.

[2] For a depressing account of how a traditionally Catholic society, based on what we would now call integralist principles, was obliterated, read Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars.