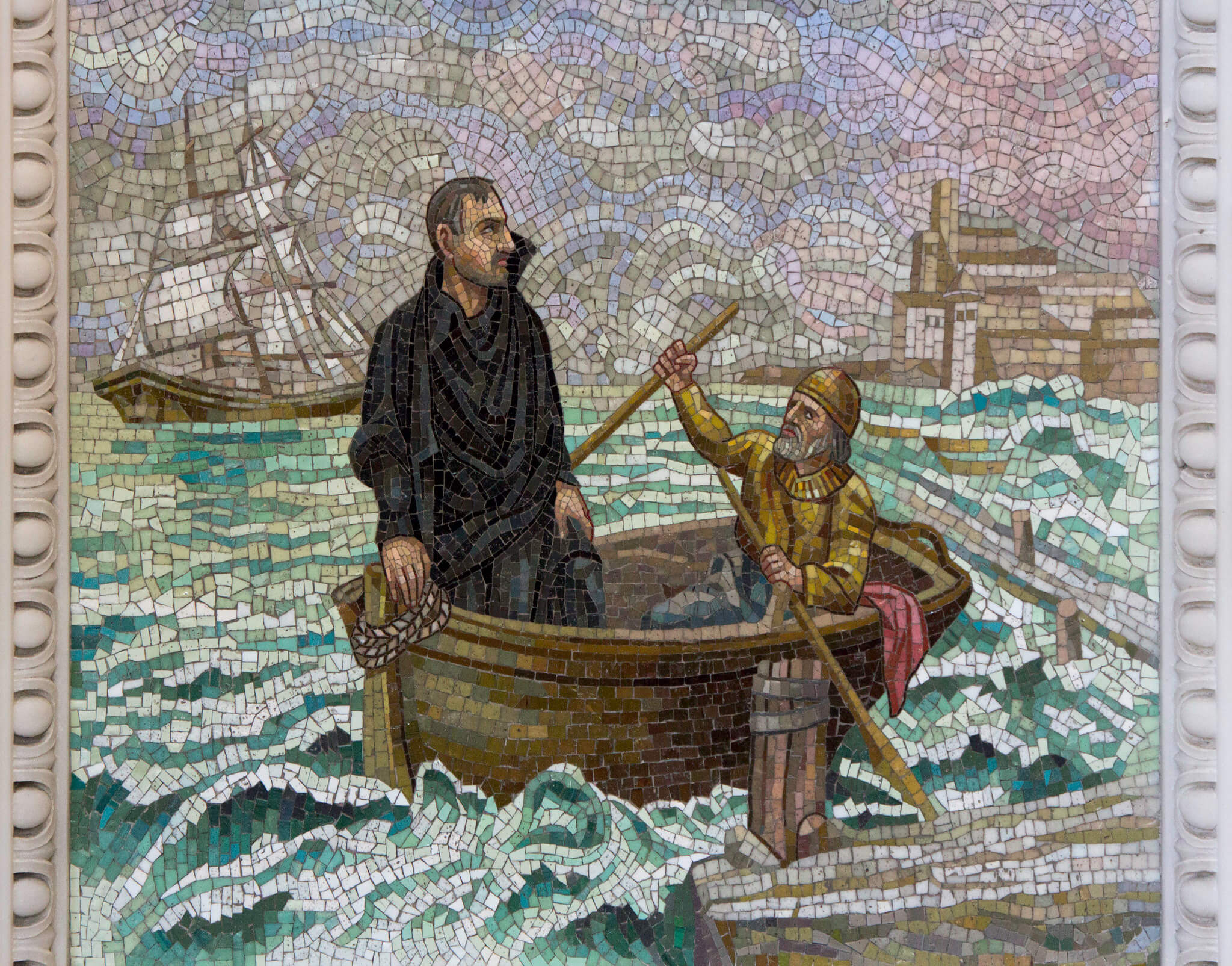

Above: mosaic of St. John Ogilvie returning to Scotland where he was martyred by heretics in 1615. Photo by Fr. Lawrence, OP.

Part I: Seeing Holy Mass with Benedictine Eyes

Part II: Seeing Holy Mass with Carmelite Eyes

Part III: Seeing Holy Mass with Dominican Eyes

Part IV: Seeing Holy Mass with Franciscan Eyes

The old saying, “as lost as a Jesuit in Holy Week,” might be on the minds of some skeptics as they scan the title of this last installment in my series on how major schools of spirituality can help us peer further into the inexhaustible riches of the Mass.

It is true that there are certain tensions between the Benedictines and the Jesuits when it comes to appreciating liturgical prayer, and that the Jesuit spirituality is not exempt from criticism on this point,[1] as well as on the notion of obedience perinde ac cadaver, obeying as if one were a corpse moved around by another.[2] Yet we must not forget about the heroes, the giants, of the Society of Jesus, who are inseparable from the sacred liturgy in its traditional form.

Picture St. Ignatius in vigil at Monserrat, the Benedictine monastery to which he frequently repaired during his year in the cave of Manresa. Let us recall Ignatius taking vows before the Sacred Host held in St. Peter Faber’s hands at the Chapel of St. Denis. Let us remember how he praised the Divine Office and the fittingness of beautiful liturgy, how he encouraged frequent Confession in preparation for Holy Communion, and the allusions to sacred imagery and architecture in the Spiritual Exercises. Let us admire how he prayed for eighteen months after ordination before daring to offer his first Mass at the basilica of St. Mary Major in Rome.

Now picture St. Edmund Campion’s pastoral heart, which urged him to come out of hiding for one more Mass and preaching request—though an intuition made him think it might be a trap. He was willing to risk everything for the sake of bringing souls to Christ and Christ to souls. He knew that the Protestants could not offer the Sacrifice or the Eucharist.

Summon to mind St. Isaac Jogues, feeling around with his bare feet in the cold water of the ravine at Ossernenon to locate the remains of his companion “while singing as best I could the prayers the Church sings for the Dead,” and then, arriving back in France a year later and attending his first Mass in a long time, which occasioned the remark: “I began to live again.” Then, of course, he received his dispensation to say Mass without the canonical digits, which had been sawed off by the Iroquois warriors, and returned to Canada to continue the mission that would end in his martyrdom.

Our journey through the Mass has brought us to the end. After Communion, after the purifying of the vessels and the clearing of the altar, we hear the stirring words: Ite, missa est!

But why does the Mass include these words? Ite, missa est doesn’t really mean “Go, the Mass is ended.” It literally means: “Go, it is sent.” What is sent? Ah, that has been a debated question for centuries! The Latin phrase itself is curiously open-ended. Some commentators say that it means: “The sacrifice of Calvary is sent up to the Most Holy Trinity.” This would seem to be confirmed by the prayer that follows right after the Ite missa est in the Roman Rite:

May the lowly homage of my service be pleasing to Thee, O most holy Trinity: and do Thou grant that the sacrifice which I, all unworthy, have offered up in the sight of Thy majesty, may be acceptable to Thee, and, because of Thy loving kindness, may avail to make atonement to Thee for myself and for all those for whom I have offered it up. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

It is also defensible, however, to view the Ite missa est as referring to the body of Christ sent into the world: the Mystical Body of Christ whose unity is expressed and accomplished by the Eucharistic Body of Christ. His faithful ones are sent forth into the world. Ite, missa est: “Go, you are sent to do the Lord’s work, in the strength of the Sacrifice He has made for us. You are sent into the vineyard by the Son who was sent to save the world.”

This is what brings us to Ignatian spirituality, which focuses on mission (missio, sending). The annals of the Jesuits are filled with models of missionary zeal, men who are sent into the most difficult and desperate of situations: St. Edmund Campion and the many daring Elizabethan undercover, underground Jesuits (we could use a bunch more of those in the era of Traditionis Custodes!); St. Francis Xavier and Fr. Matteo Ricci, who preached in the Orient; St. Isaac Jogues, St. Jean de Brébeuf, St. Charles Garnier, and companions, who preached to the Indian tribes of North America; Père de Smet, who celebrated the first Mass in Wyoming territory—men of that caliber. They did nothing in half measures: they gave everything to the last drop of their blood and sweat. They walked into the arms of their enemies, preaching the Gospel all the while. They converted many, and were often rewarded with the most horrendous tortures for love of Christ and souls.

The spirituality of these heroes of faith could be summed up in a famous saying attributed to St. Augustine: “Pray as if everything depended on God; work as if everything depended on you.” Whatever you are doing, give yourself completely to it. I’m reminded of what St. Teresa of Jesus allegedly said to someone who observed that she had quite a good appetite: “When I pray, I pray; when I eat, I eat.” Age quod agis: really do what you are doing. Give yourself time to pray, and in that time, pray as well as you can, and as well as God gives it to you to do. And when you are finished with the time of prayer—be it Mass, a Holy Hour, the Rosary, or what have you—then go forth and work as if everything depended on you, depended on your enthusiasm, your dedication, your labor.

The example left to us by the classic Jesuit saints is a challenging one—nothing less than the narrow way of denying ourselves the easier path we might have chosen, the kenosis or self-emptying that leads to eternal life. We all falter on this path, and we will keep falling, but we know that what matters is to persevere under holy obedience (rightly understood) and go forward with confidence in God. If I may draw upon a non-Jesuit for a moment, here is what Padre Pio says: “The life of a Christian is nothing but a perpetual struggle against self; there is no flowering of the soul to the beauty of its perfection except at the price of pain.” Padre Pio is not one who pulls any punches, and he tells it like it is.

The point of it all, however, is not suffering, but joy. As St. Paul tells us in the Letter to the Romans: “I reckon that the sufferings of this time are not worthy to be compared with the glory to come, that shall be revealed in us” (Rm 8:18). What matters now is to keep striving, keep begging for the Lord’s help, and never lose heart, because God is our refuge, our strength, our hope, our Savior. He will never abandon us if we do not abandon Him. The path on which he has called us is a path, ultimately, of joy—and our joy is what brings God the greatest glory. As St. Irenaeus put it: “The glory of God is man fully alive”—but let us not forget the conclusion: “and man’s life is the vision of God.” The life God wishes to see in us is His life, which shines through our faith, humility, obedience, and zeal.

Here we may note a crucial difference between the Novus Ordo and the Tridentine Mass.

Unlike its attempted replacement (the modern Mass of Paul VI), the authentic Roman Rite wisely does not conclude with the “Ite, missa est.” Instead, having uttered these words, the priest prays the Placeat tibi as mentioned above, and then gives a double blessing: first, what we usually call the blessing (“Benedicat vos omnipotens Deus…”), and then the “blessing” of the Last Gospel, the Prologue according to St. John. It appears that in the Middle Ages the faithful regarded it as a special blessing to have this Gospel read over them (the priest originally read it as a private thanksgiving), and so by the time we reach the missal of Pius V, the Gospel is fully integrated into the Order of Mass. I have spoken elsewhere about the fittingness of this custom, but here I merely wish to point out that “mission” does not have the last word in the traditional Mass. The last word is given to the Word made flesh, full of grace and truth. The last word is given to God’s blessing, without which nothing that we do will ever be good, holy, or fruitful; the last word is given to His truth, without which our “truths” will be half-truths at best, and lies at worst.

That is what is essentially missing from the self-styled modern Jesuit: for him, mission has become everything, and the Mass truly ends with “Go,” not with blessing, grace, and truth. In an ironic twist, one might even say that the final word of the liturgical reform itself—the reform that mangled the Mass in countless ways—was: “Go, the Mass is ended,” that is, the Mass of the Roman Rite has been terminated. Or so they vainly believed; but history has proved otherwise, and “the once and future Roman Rite,” in spite of being persecuted by a certain famous Jesuit, is never going to end short of the Parousia.

“The Eucharistic sacrifice is the font and apex of the whole Christian life” (Lumen Gentium 11). The Benedictines and the Carmelites show us how the Mass is a microcosm of the entire spiritual life. The Dominican tradition tells us that we should treasure the intellectual life and see it reaching a pinnacle in the study and preaching of divine Truth. The Franciscan school urges us to discern God’s eternal attributes in the temple of creation, and to sanctify all creatures by our wise use of them: a teaching about cosmic and holistic life. The Ignatian tradition sets before us the missionary zeal, integrity of character, and fortitude of spirit that are essential for Catholics who wish to survive and thrive in the modern world: a teaching about life in the world, in the home, the streets, the marketplace, the academy, wherever the Lord takes us—provided we take Him with us by receiving His blessing, pleading for His grace, and adhering to His truth.

These schools of spirituality help us to see how the Mass is a lifelong school for all Christians: the place where we will learn who we are and what we are called to do, the time that will bind up and heal the varied parts of our days, the center that holds the spheres in their orbits. Let us seek out the source; let us climb to the summit.

[1] See on this point my two articles at NLM: “The Ironic Outcome of the Benedictine-Jesuit Controversy” and “Objective Form and Subjective Experience: The Benedictine/Jesuit Controversy, Revisited.”

[2] See John Lamont, “Tyranny and Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church: A Jesuit Tragedy.” A very fine traditionalist Jesuit I know claims that Lamont’s position is somewhat exaggerated and that one can find sound principles and correctives within the Jesuit tradition itself. Nevertheless, there is a sort of popular “distillation” of certain Ignatian views that has arguably caused immense havoc. See my work True Obedience on the correct understanding of this important but misunderstood virtue. Be that as it may, let us remember the luminaries of the order such as St. Robert Bellarmine and St. Peter Canisius, both of whom would have spewn forth as error the theological positions advanced by many of their modern brethren.