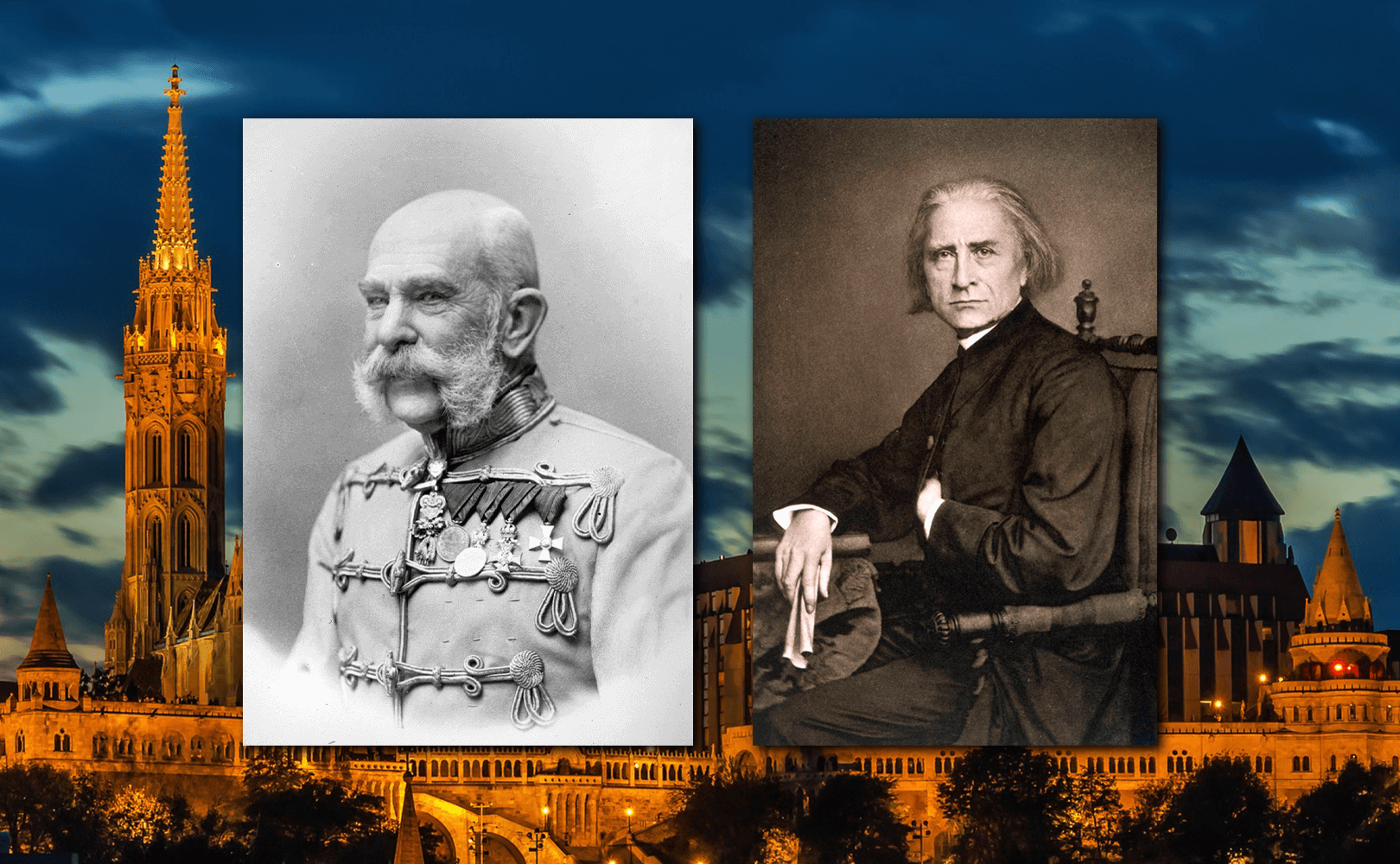

190 years ago today, on August 18, 1830, His Apostolic Majesty Franz Joseph (1830-1916), the penultimate emperor of Austria and king of Hungary, was born in Schönbrunn Castle near Vienna. He reigned for 68 years, from 1848 until the First World War.

Going through a portrait gallery of the members of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, heir of the Holy Roman Empire, we would see Franz Joseph as an elder who worked “behind his very neat desk as his entire Empire was well-ordered,” in uniform, as is appropriate for the “first servant of the state” — as he proudly believed himself — dealing with a lot of paperwork (cfr. C.L. Cergoly, Il complesso dell’Imperatore, Mondadori 1979, pp. 186-187). He bore the not insignificant weight of a truly heterogeneous and vast empire, which, in 1910, numbered about 51 million inhabitants. And he endured his share of personal mourning: Maximilian, his younger brother, archduke of Austria and emperor of Mexico, was shot and killed there in 1867; Rudolf, his only son, hereditary archduke, committed suicide in Mayerling in 1889; Elizabeth of Bavaria, his wife, the famous Princess Sissi, was murdered in Geneva by an Italian anarchist in 1898.

It is primarily the events of the deaths of Prince Rudolf and of Empress “Sissi” that have attracted the interest of posterity, moreso, at least, than the deeds of the reserved, sober Kaiser of few words. His inability to dominate the growing national demands of the peoples of the Empire and his declaration, unwillingly, of war on Serbia, the spark that ignited the First World War, seem to be his most notable legacy.

At the end of the negotiations regarding a new order of the Empire, with two states under one sovereign, on June 8, 1867, the archbishop of Esztergom, János Simor, primate of Hungary, received on the edge of the Matthias Church both the emperor and empress to crown them solemnly kings of Hungary. The commission to provide a coronation mass was entrusted, not without dissension, to the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt (1811-1886), who on Palm Sunday, April 14, 1867, wrote to Baron Anton Augusz, his admirer and friend: “Today I finished my Coronation Mass. In God’s grace. In manus tuas commendo spiritum meum [into your hands I commend my spirit]” (in Liszt Ferencz levelei báró Augusz Antalhoz, 1846-1878, ed. Csapó Vilmos, Budapest 1911, 119).

In Rome, where Liszt resided between 1861 and 1869 and took minor orders on October 25, 1865, the Hungarian cleric and musician composed over the course of three weeks the Ungarische Krönungs-Messe (Hungarian Coronation Mass) for soloists, chorus, and orchestra: about 45 minutes of music that requires soprano, alto, tenor, bass, mixed choir, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, bass tuba, timpani, organ, and strings. It is divided into six movements, to which were added the Offertory, after the first performance, and the Gradual, two years later.

Liszt, whom court etiquette would not allow to conduct his own composition, witnessed the service and the performance of his music from the choir loft, conducted by Gottfried von Preyer, who had been the choirmaster at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna since 1853. In his letter, written the same day from the city of Pest (the Eastern portion of what is now Budapest) to Princess Carolyne in Rome, Liszt expressed his satisfaction with the result: “I believe you will be satisfied. The musical success of my Mass is complete. It surprised everyone by its brevity, its simplicity, and — if I dare say it — by its character” (A. Williams, ed. Franz Liszt. Selected Letters, Clarendon Press, 1998, p. 665).

In fact, the Hungarian “character,” the national aura, as it were, is well highlighted in this Mass, with its ancient Hungarian themes elaborated with cleverness and faith. A couple of examples will suffice. The Gloria (Allegro giusto in 4/4), which begins on the notes of the fanfare of the Rákóczy March — the Hungarian national march — immediately presents itself as a very lively hymn of victory, till the supplicant Qui tollis peccata mundi, in which the Hungarian descending scale, often used by Liszt, is heard. At the beginning of the Benedictus another beautiful national but religious melody is entrusted to a luminous violin solo.

Returning to his usual accommodation at a church in Pest, our composer experienced an episode that sounds as though it were taken from a work of fiction: “When the feverish suspense grew intense, the tall figure of a priest, in a long black cassock studded with decorations, was seen to descend the broad withe road leading to the Danube, which had been kept clear for the royal procession. As he walked bareheaded, his snow-white hair floated on the breeze, and his features seemed cast in brass. At his appearance a murmur arose, which swelled and deepened as he advanced and was recognized by the people. The name of Liszt flew down the serried ranks from mouth to mouth, swift as a flash of lightning. Soon a hundred thousand men and women were frantically applauding him, wild with the excitement of this whirlwind of voices. The crowd on the other side of the river naturally thought it must be the king, who was being hailed with the spontaneous acclamation of a reconciled people. It was not the king, but it was a king, to whom were addressed the sympathies of a grateful nation proud of the possession of such a son” (J. Wohl, Francois Liszt: recollections of a compatriot, London: Ward & Downey, 1887, pp. 20-21).

This mass features music that isn’t sumptuous, despite what the idea of a coronation would suggest. It has a simple tone and a non-theatrical atmosphere, which anticipates the guidelines against the influences exercised by secular music, especially opera, issued in Pope St. Pius X’s motu proprio on Sacred Music, Tra le sollecitudini, on November 22, 1903. It has a very daring style, as in the case of the Credo, which, paraphrasing the modal melody of the Missa Regia by the French composer and harpsichordist Henry du Mont (1610-1684), is full of neo-Gregorian charm; of the Offertory, purely instrumental, such as those for organ by Frescobaldi and Couperin; and of the aforementioned Benedictus solo, similar to that of grandiose Missa Solemnis by Beethoven.

It is said that Franz Joseph, who did not in general appreciate music much, liked the work of Liszt even less, so much so that he didn’t even invite him to the banquet on August 31, 1855, after the consecration of the Cathedral of Esztergom, for which the Hungarian composer had written the “Gran” Mass (cfr. P. Rattalino, Liszt o il giardino d’Armida, EDT, Torino 1983, p. 90). Perhaps on the day of his coronation, the crown of Saint Stephen, the first king of Hungary, made him change his mind about Liszt.