In early August of 1968, a stylish and brilliant convert from Anglicanism, and at this time a pastor of a flourishing parish in Suffolk, was driving his “fast and comfortable Jaguar” from Bury St Edmunds to London. He took a friend, Edgar Hardwick, parish priest of Coldham, with him. When he pulled up to his friend’s place, the friend got in, holding a newspaper.

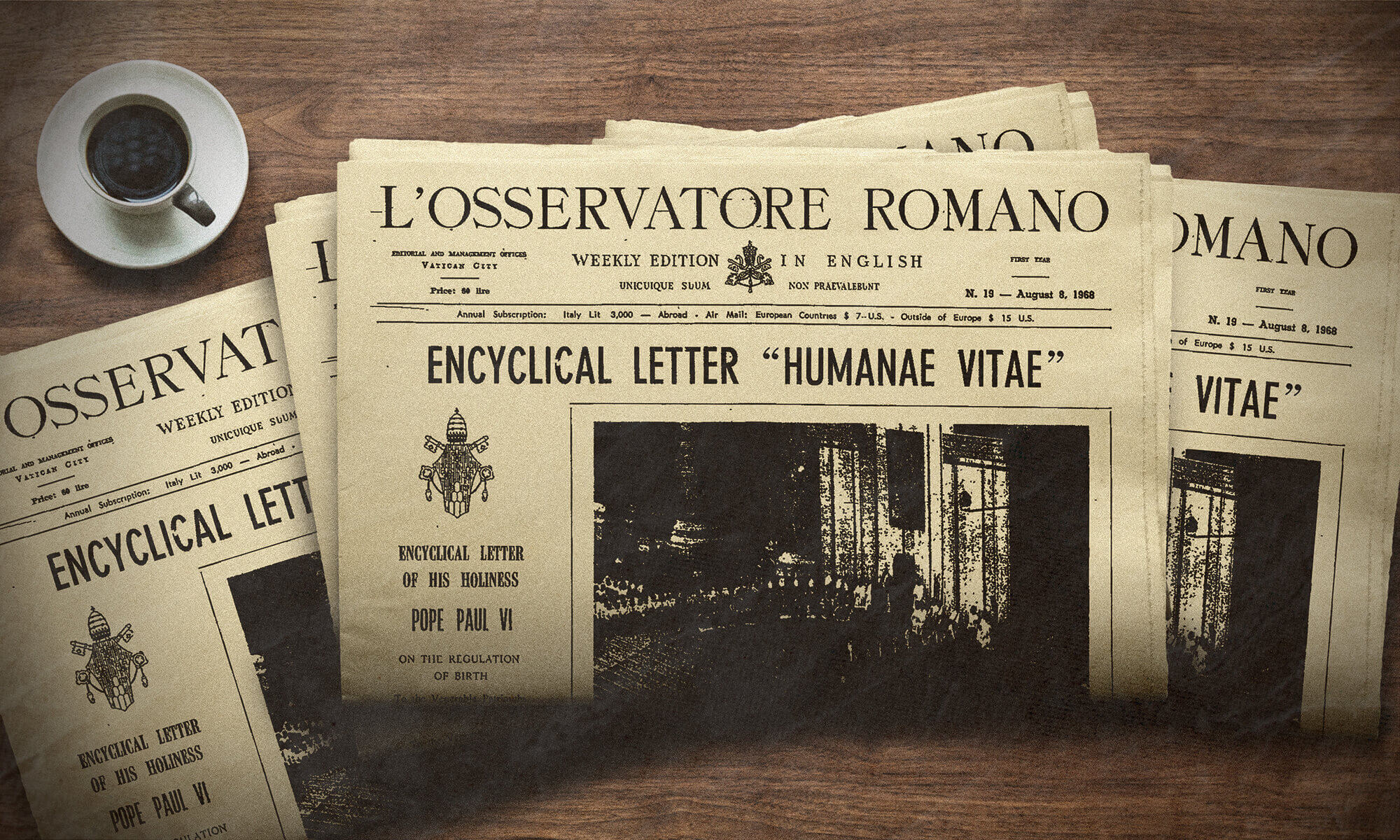

He let me drive for about twenty minutes and then asked me: “Have you seen today’s paper?” “No,” I replied, “I haven’t taken a paper since 1954.” “But I think this may interest you,” and he started to read something: it was Humanae Vitae. Luckily there was a layby to get off the road. I stopped the car and listened. Humanae Vitae was quite perfect. Edgar was a bit surprised when I hugged him and kissed him on both cheeks. “The Catholic religion is true,” I cried; “one can trust the Church; salvation is real!” I drove up to London with a song in my heart. But it had been a very near thing. Could I have lasted another three months? I doubt it.[1]

In his sparkling, at times biting, autobiography Unwanted Priest—the English manuscript of which was completed in 1990 but then lost and only rediscovered a few years ago, and happily published by Angelico Press in 2022—Fr Bryan Houghton (for it is of him that we speak) allows us a momentary peak into his mid-1960s crisis of faith. It hinged on the question of contraception. As he explains:

The liturgy was not the only object of reform in the conciliar Church. There were plenty of others, such as married clergy, priestesses and so on. But one object of reform appeared to me particularly dangerous: the attempt to make a papal bull swallow the pill. Vernacular liturgies and the like were merely working up to the humanitarian right to contraception.

It came up officially in the fourth session of the Council, in September 1965. The outcome was [considered to be] certain. A great number of Catholic women started taking the pill. But the Council reserved the issue to the Holy See. The Council closed on December 8th, 1965, having gone as far as it could to disrupt the Church.

I was only an humble parish priest. I had to hear confessions for three or four hours every Saturday. “I have taken the pill three times; it seems to me alright.” What am I to answer? In fact, I answered that it was all wrong. But will they believe me?

Here comes the rub. The Catholic Church claims to be of divine institution. It consequently teaches infallibly what one must believe and do for one’s salvation. But for how long can what one must do for one’s salvation be left in doubt? Not for a second, let alone for four years.

I gave my replies in the confessional in a second—but I had a gnawing doubt about Rome. If Rome allowed the pill, then clearly its pretensions to infallibility were nonsense. My conversion to Catholicism was an hallucination—as well as my poor attempts to holiness! I might as well commit suicide….

In 1965 the Council remitted the “problem of the pill” to the Holy See. The Holy See appointed a commission to discover what was right and wrong. A leak in 1967 said that the majority of the commission was in favour of the pill. Were all my instantaneous decisions in the confessional wrong? Worse than that, over the years thousands of women must have acquired the habit of the pill. Whose fault would that be—if not that of the Church herself?

I was very depressed. The Church must be wrong, since she is incapable of giving an answer to a straightforward moral problem.

And it was just at that critical moment in his life that Edgar handed him the newspaper with the text of Humanae Vitae. Fr Houghton’s faith in the infallibility and indefectibility of Holy Mother Church had been vindicated, and he could give sound advice and penances with a clear conscience and a living faith.

Fr Houghton was not a naïve adulator of Paul VI—by no means. Not for him the recent habit of bestowing halos like the Queen’s Birthday Honours. He saw the wreckage and damage that the liturgical reform had wrought, writing in a parody of the hymn “The Church’s One Foundation”:

The Church’s transformation

By Paul VI our Pope

Has left for contemplation

A void deprived of Hope,

Where charity is wanting

And faith is fled as well.

One hears above the chanting

A little hiss from hell.The priest is now our ruler

Or “president” they say.

He uses vērnacūlar

To teach us not to pray.

He has a facing altar

To regiment his band

And, should our voices falter,

A microphone to hand.[2]

It was, in fact, precisely the going-into-effect of the Novus Ordo Missae on November 30, 1969, that “triggered” Fr Houghton’s long-premeditated decision, declared in advance to his bishop in writing, to resign his curacy rather than say the new liturgy. He then retired to Provence—he was fully fluent in French, having attended French schools as a boy—where he expected to be saying private Masses for the rest of his life. Instead, Divine Providence gave him a wonderful local congregation of French people eager to keep their tradition intact and desperate to get away from the rampant novelties of the day. A grand lady, Madame Vallette-Viallard, a convert daughter of a Protestant banking family—“she was very conscious of having changed her religion once, and she was not going to change it again. She could not stand the new Mass, which forcefully reminded her of what she had rejected”[3]—helped him organize a roster of Masses, which, it may be noted, enjoyed the toleration, if not support, of local church authorities.

Fr Houghton’s crisis of faith hinged on the question of contraception, and for good reason. The Church has taught consistently that contraception is intrinsically evil, that is, no circumstances can ever render it good. Married couples take upon themselves in marriage a grave duty before Almighty God to observe His law[4] and to welcome generously the children He wishes to bestow, since their relationship is ordered to the family: that is indeed the fundamental reason God brings together man and woman in nuptial union, the reason without which marriage would not exist at all. Contraception is condemned as sinful in any and all circumstances in many magisterial documents, such as Pius XI’s Casti Connubii (1930), Pius XII’s Address to Midwives (1951), Paul VI’s Humanae Vitae (1968), and, of course, a host of documents by John Paul II, who devoted a considerable portion of his teaching to the explication and defense of his predecessor’s teaching on just this point.

Here it is not my intention to argue for the teaching, but simply to say that Fr Houghton was quite right to have a crisis of conscience on this point. Either the Church has been right to condemn this practice as mortal sin and to expect the faithful to avoid it at all costs (or to repent of it if guilty), or the Church’s claim to be the moral teacher sent by God, absolutely trustworthy in interpreting His law and laying down the requirements of salvation, is null and void. There isn’t any wiggle room here for a slippery “development of doctrine” that would eventually turn black into white and white into black.

Enter the refurbished Pontifical Academy for Life [PAL], whose statutes by command of Pope Francis were rewritten and whose membership was purged in 2016 to be replenished by a cadre of clergy and scholars more amenable to the pope’s line. As Jonathan Liedl reported on July 13, this “paradigm shift” in moral theology “would include departing from established teaching on contraception, but also euthanasia and forms of artificial conception.” As Luisella Scrosati explains:

The book Etica teologica della vita. Scrittura, tradizione, sfide pratiche [Theological Ethics of Life. Scripture, Tradition, Practical Challenges], just published by the Vatican Publishing House (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), gathers the fruits of a three-day interdisciplinary Seminar, promoted by the Pontifical Academy for Life; a Seminar that, according to its President, Msgr Vincenzo Paglia, would be unique, as it aimed at ‘opening a dialogue between… different opinions, including on controversial topics, offering many points for discussion.’… Obviously all in a climate of parrhesia and, according to Paglia, ‘with a procedure analogous to the quaestiones disputatae: to put forward a thesis and open it up to debate. And the debate can lead to glimpses of new paths, in order to advance theological bioethics.’

The book “supports the thesis that ‘in conditions and practical circumstances that would make the choice to generate irresponsible,’ one could resort ‘with a wise [prudent] choice’ to contraceptive techniques, ‘obviously excluding any that are abortogenic’”; it also proposes the approval (again, “in certain cases”) of artificial insemination to bring “to completion what the sexual relationship of these [infertile] spouses cannot achieve. Technique cannot be rejected a priori in medicine: it must be made the subject of discernment, to ascertain whether it fulfils the function of a form of care for the person.” Fr Jorge José Ferrer, S.J., who officially presented the proceedings of the seminar, praised Pope Francis for bringing about “a decisively renewed configuration of the theological ethics of life, far removed from the rigorism that still fuels some ecclesial discourses and contributes to a caricatured vision of Catholic morality that we frequently find in the media, social networks and popular perception.”[5] He contrasts the letter of earlier Vatican documents with their supposed spirit, in order to make room for (you guessed it) a “development of doctrine.” Note how right Benedict XVI was to indicate the letter/spirit contrast as a prime maneuver among those who would make Vatican II their Trojan Horse.[6]

We’ve seen this trick before. As Larry Chapp has pointed out on social media and in his recent excellent revisiting of Amoris Laetitia (see, e.g., here and here), the strategy of the underminers of Catholic moral doctrine is always the same. They more or less accurately summarize the traditional teaching but then slyly, often with gestures of head-shaking and hand-wringing, relegate it to the lofty pedestal of an “ideal” to be admired, yet to which exceptions must sometimes be made in “practice.” After all, God is merciful, and asks of people only what they can do. Maybe all they can do at a certain time is sleep with someone not their spouse, or use contraceptives; and that is what God asks of them as they journey, accompanied by their pastors, to a deeper appreciation of Christian values.

Never mind that Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI explicitly and unequivocally rejected this line of argument. Never mind that faithful Catholic scholars from around the world have carefully documented the authoritative teaching of the Church as well as ways in which Francis and his court have contradicted it again and again. Today’s Vatican has “moved on” and “moved forward” from those rigid, judgmental, moralistic, categorical, Tridentine ways of thinking. “We think differently about these things than we used to… we know more now than we did before… we understand better the limits and possibilities of the individual based on psychology and sociology…”

The progressivists seem, ironically, to be incapable of “reading the signs of the times,” which show that low-demand, low-commitment religion is dying under the withering blasts of secular modernity, while high-intensity, high-focus religious practice is growing.[7] The proponents of the pseudo-magisterium of mercy try to appeal to the indifferent, the disaffiliated, and the barely believing by watering down the good news of grace, which the Church alone can bring, and offering them redundant worldly platitudes, as if the Church’s purpose were rather to bless their estrangement from Christ than to call them to conversion and true life in Him.

Scrosati sardonically concludes: “This is the new mission of the Pontifical Academy for Life and its President: to change the paradigm, opening to what the Church has clearly closed and inflexibly closing on what must instead remain open. A rather original way of understanding the power of the keys.”

The most disturbing rumor of all is that the Pope may be preparing a new encyclical on sexual morality and life issues—a sort of Humanae Vitae 2.0, the updated version. Its code name is Gaudium Vitae. If it really comes to pass, it is expected to include some of the “new horizons” that Fr Jorge José Ferrer so praises in the PAL proceedings.

It would, in other words, be the realization of Fr Houghton’s worst nightmare of the 1960s.

Make no mistake about it: “all things are connected,” as Pope Francis frequently says, echoing the environmentalists of whom he is so fond. All things indeed are connected: this acidic, serpentine, back-alley dissolution of Catholic morality on the most fundamental matters; the general doctrinal haze, smog, and pollution generated by this pontificate and its opportunistic satellites; and the mounting attacks on traditional Catholic faithful and the magnet that draws them together, the Mass of the Ages, now deemed incompatible with the ecclesiology of Vatican II and “its” [sic] liturgy.[8]

I do not for a moment believe that a pope has authority to overthrow the Church’s teaching on contraception, in vitro fertilization, euthanasia, etc., any more than he has authority to reverse the Church’s tradition on the legitimacy of the death penalty or the forbiddance of communion to the divorced and remarried living more uxorio. But as we have seen, a renegade pope may attempt to do so, causing immense harm in the process.

Alas, unlike Fr Houghton, I don’t have a fast and comfortable Jaguar to get into; but if one morning I pick up a friend and find him waving his phone, ready to tell me about a just-released encyclical, I surely hope and pray it will reaffirm the faith of God-fearing Catholics, and not throw them into confusion or desperation. We are weary to death of this ¡Hagan lío! pontificate and wish nothing more than for Christ our Lord to reestablish peace in the unity of the truth.

[1] Bryan Houghton, Unwanted Priest: The Autobiography of a Latin Mass Exile, ed. Gerard Deighan (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2022), 92. This book deserves a more extended review, which I hope to give it; but take my word for it, it’s beautifully written, quite funny at points, and crammed with insights.

[2] Ibid., 114.

[3] Ibid., 110.

[4] This is not the place to get into the decades-long debates over NFP. I have articulated both the inherent difference between NFP and contraception in this article, and the danger of abusing NFP in this article.

[5] All quotations from Scrosati. See also the article in Pillar Catholic.

[6] See the address to the Roman Curia on December 22, 2005. Pope Francis has himself taken the false view on more than one occasion; see, e.g., this write-up.

[7] There are many books and articles about this phenomenon. See, e.g., Colleen Carroll, The New Faithful: Why Young Adults Are Embracing Christian Orthodoxy (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2002), and, more recently, Joseph Shaw, The Case for Liturgical Restoration (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2019), 207–97.

[8] This is the claim made by Francis in Desiderio Desideravi 31. As Alcuin Reid says here, the view that the Novus Ordo is “the liturgy demanded by Vatican II” is an “elephantic lie.” No less dubious is the view that the ecclesiology of Vatican II is essentially incompatible with the very liturgical rites that the Council Fathers themselves celebrated. For more on this most important topic, see these articles: “Daringly Balanced on One Point” and “The Old Liturgy and the New Despisers of the Council.” There are, needless to say, many, many relevant articles that could be cited on this head.