“My first and last philosophy, that which I believe in with unbroken certainty, I learnt in the nursery. I generally learnt it from a nurse; that is, from the solemn and star-appointed priestess at once of democracy and tradition. The things I believed most then, the things I believe most now, are the things called fairy tales. They seem to me to be the entirely reasonable things. They are not fantasies: compared with them other things are fantastic.”

-G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

I will never forget how I felt as a child, trying to fall asleep so that Santa could at last do his joyous work. On Christmas mornings, there were always a few gifts from him, wrapped up in different paper than any of those given by my parents. One year, I wrote a letter and got one back in handwriting I was convinced did not belong to anyone in my house. Another year, I sat in rapt attention before the giant, wood-encased television at my grandmother’s house on Christmas eve, watching as the weather man said there was something they were picking up on the radar that they simply couldn’t explain. I knew it was him. I had the certainty that only faith could give.

Years later, however, as a young father, I had developed an unfortunate strain of zeal that bordered on the puritanical. In my desire to instill in my children the unvarnished truths of the faith, I neglected to cultivate in them a proper sense of wonder. When our oldest daughter was about six years old, I informed her (rather unceremoniously) that Santa Claus was not real. At the time, I believed I was doing her a favor. Surely, she was better off knowing the true story of Christmas without the added distraction of the strangely aggrandized myth of St. Nicholas. After all, I had been told again and again over the years that he was nothing more than an artifact of our disastrously consumer culture. And when I was growing up, hadn’t I known other families who received their gifts on Christmas morning from “the Baby Jesus”? They seemed perfectly well-adjusted.

What I wouldn’t come to understand until quite a few years later was this: in vanquishing the jolly old elf from my daughter’s imagination, I had chased away with him a large portion of the sense of awe that properly pertains to the miracle of Christ’s birth.

To a child, magic is not at all an outlandish thing. They live every day in a world of endless possibilities. Around any corner, there might be a fire-breathing dragon; under every bed or in the dark corners of any closet, a horrible lurking monster. The living room sofas and their scattered pillows are merely islands of safety amidst a sea of molten lava. Fairies are no doubt real if you stay up late and go out deep enough into the woods to catch one. Countless hours are spent discussing amongst themselves just which three things they’ll wish for when they finally come across an ancient, genie-filled lamp.

To the Christian parent in a world awash in resurgent paganism — from wicca to witchcraft to the heathen followers of the Norse pantheon — such flights of childish fantasy can at times seem tinged with danger. For the same reason certain exorcists warn mothers and fathers about Harry Potter as a possible gateway drug to the modern-day occult or the spiritual death trap of brightly-packaged Ouija Boards available at any toy store, the 21st-century follower of Jesus looks askance at any myth that seems poised to further diminish the Christian ethos.

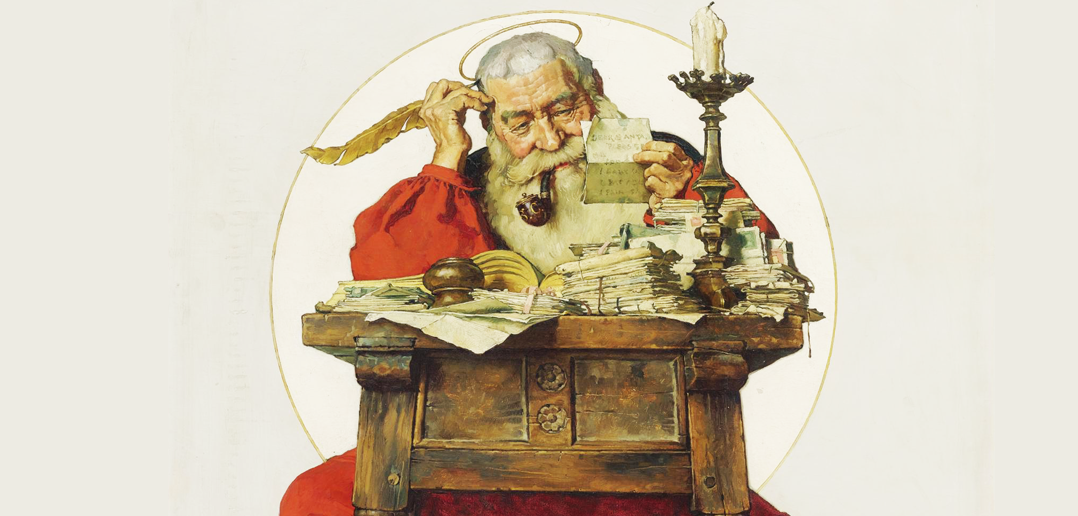

Still, I propose that we reconsider our quotidian suspicions — though often justifiable — when it comes to Old St. Nick. Why should our children not contemplate this mysterious (if almost entirely mythologized) saint, ever unseen but as consistent as clockwork, who loves us so much that he gratuitously brings gifts to the children of the entire world, accomplishing superhuman feats of logistics and undetectable intrusion all in the course of one cold and starry night as we ready ourselves to celebrate the birth of our Heavenly King? We know that he expects the best from us, but we sense, as we imagine his twinkling eyes and barely-concealed smile beneath the downy drifts of his magnificent beard, that he wishes for all the world to find whatever small goodness we have done and nurture it into a roaring flame of virtue, like a glowing ember found beneath the ash pile of our misdeeds and sins. Santa Claus embodies what is most attractive about fatherly goodness; he is stern not from cruelty or anger, but because he earnestly desires our right action. He is loving and kind not because he is soft and emasculated, but because he wants to share the goodness of his great bounty with us, and so ennoble us by his gifts.

In the blossoming young mind, the almost unbearable excitement of the Santa Claus story, properly cultivated, can’t help but set the stage for the incredible mystery of the Infant Christ, who comes to us as an unmerited gift to grant us every good thing; Whose very blood was shed to show us the great mercy of God and the infinite bounty of heaven.

In 1904, Chesterton wrote of his own ever-growing belief in the idea of Santa Claus:

What has happened to me has been the very reverse of what appears to be the experience of most of my friends. Instead of dwindling to a point, Santa Claus has grown larger and larger in my life until he fills almost the whole of it. It happened in this way. As a child I was faced with a phenomenon requiring explanation; I hung up at the end of my bed an empty stocking, which in the morning became a full stocking. I had done nothing to produce the things that filled it. I had not worked for them, or made them or helped to make them. I had not even been good— far from it. And the explanation was that a certain being whom people called Santa Claus was benevolently disposed towards me. Of course, most people who talk about these things get into a state of some mental confusion by attaching tremendous importance to the name of the entity. We called him Santa Claus, because everyone called him Santa Claus; but the name of a god is a mere human label. His real name may have been Williams. It may have been the Archangel Uriel. What we believed was that a certain benevolent agency did give us those toys for nothing. And, as I say, I believe it still. I have merely extended the idea. Then I only wondered who put the toys in the stocking; now I wonder who put the stocking by the bed, and the bed in the room, and the room in the house, and the house on the planet, and the great planet in the void. Once I only thanked Santa Claus for a few dolls and crackers, now I thank him for stars and street faces and wine and the great sea. Once I thought it delightful and astonishing to find a present so big that it only went halfway into the stocking. Now I am delighted and astonished every morning to find a present so big that it takes two stockings to hold it, and then leaves a great deal outside; it is the large and preposterous present of myself, as to the origin of which I can afford no suggestion except that Santa Claus gave it to me in a fit of peculiarly fantastic goodwill.

The gratuitous nature of goodness is the message of Santa Claus – that we are here through no merit of our own and live lives filled with breathtaking beauty and undeserved blessings. These things are true, even if there are no such things as flying reindeer to deliver them by sleigh, or a workshop full of elves somewhere above the arctic circle busily crafting them for our enjoyment. The truth is, there are better things even than these – nine choirs of flying angels bearing God’s gifts, and an eternal kingdom full of saints drawn from the lowliest places of the earth, praying for our salvation somewhere above the heavens.

British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke famously wrote that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This is, of course, because such technology does things never before imagined; it exists outside the realm of our known horizon of possibilities. Faith is not unlike this. We believe in a God of miracles, if not magic. A God who created the cosmos and breathed life — with an intellect and free will — into nothing more grand than a handful of dust. A God who could turn water into wine, heal the sick, make the lame walk and the blind see, and raise the dead. We believe in a God who could somehow fit His omnipresence within the body of a human child, a child who grew to suffer and die for our sake on a cross. This child, our Christ, Who also rose from the dead, became truly present in bread and wine, giving the gift of Himself to those who believe in Him every day on altars all around the world.

I recall a parish tradition from my youth that I found quite touching. There was an elderly gentleman who would play Santa Claus each year and visit the children engaged in religious instruction one Sunday as Christmas approached. But once the children had had the chance to meet Santa, he didn’t disappear until the following December. At the end of the Christmas Midnight Mass, he would appear at the back of the Church and make his way slowly up the aisle, kneeling in a long moment of silent adoration before the Christmas creche before making an equally somber departure. I’m not an advocate of such innovations in the liturgy, but I admit that I always found this one well-meaning and pious.

The story of Santa Claus need not diminish the great mysteries of Christmas when it can exist alongside of them and point us in their direction. We believe in a God who is good, who gives freely, who is everywhere, who always watches – who knows if you’ve been bad or good, so be good for goodness sake! It’s not such a stretch to see that Santa Claus can be viewed as a type of Christ, and if we allow our children to believe in him, we should do what we can to ensure that he points them toward the mystery of the Incarnation and the true meaning of Christmas.

Originally published on Dec 15, 2014.