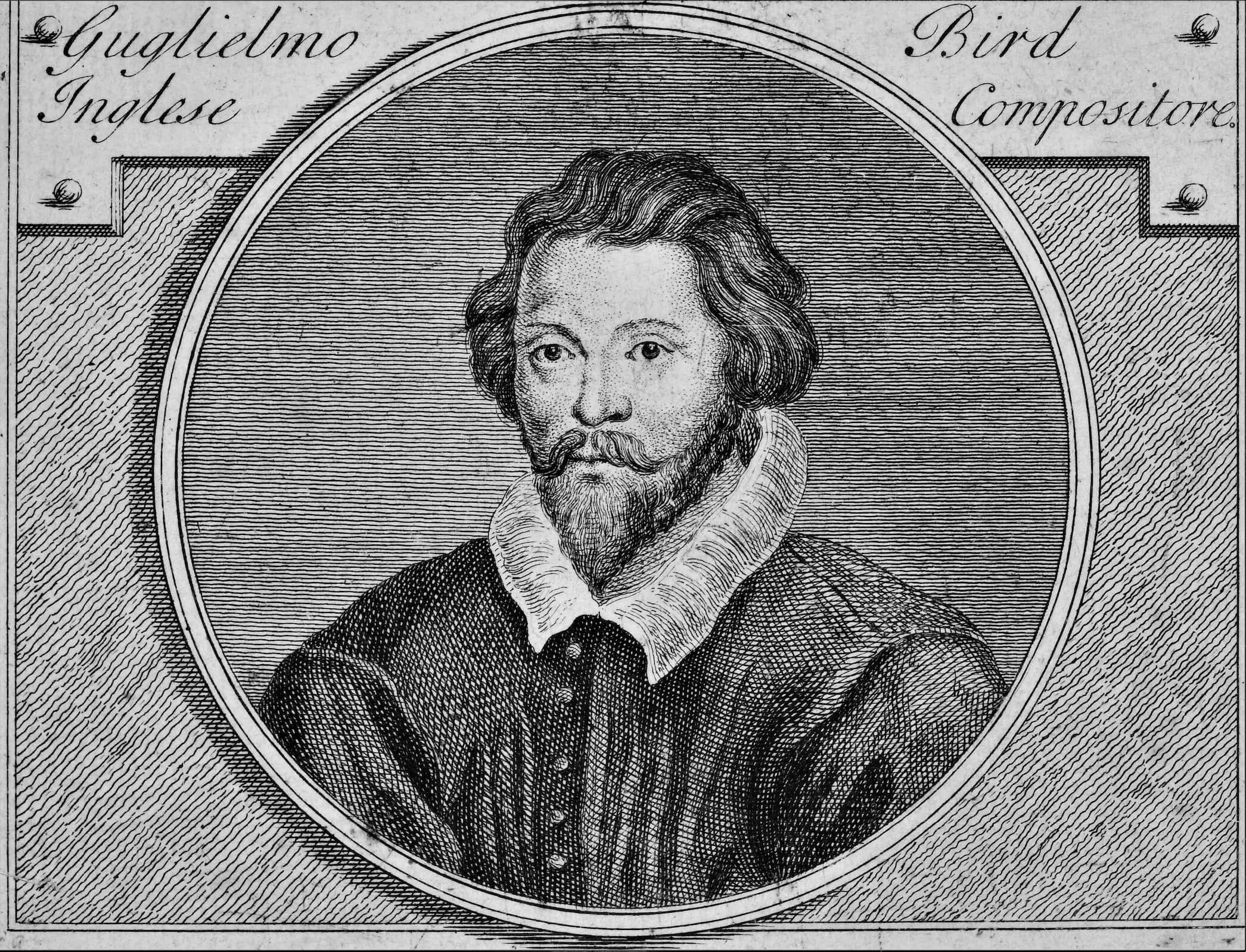

Four centuries ago, on July 4, 1623, the greatest of English polyphonists, an “obstinate papist” during the reign of Elizabeth I (excommunicated and deposed by Pope St. Pius V in 1570), died in Stondon Massey, Essex, England: William Byrd.

It is moving to read his will, in which we find his firm Catholic faith, an unusual practice for an English musician who experiences personally the terrible wounds inflicted on the Body of Christ in the sixteenth century:

I, William Byrd of Stondon Place in the parish of Stondon in the county of Essex, gentleman, do now in the 80th year of my age but through the goodness of God being of good health and perfect memory, make and ordain this for my last will and testament. First, I give and bequeath my soul to God Almighty, my creator and redeemer and preserver, humbly craving his grace and mercy for the forgiveness of all my sins and offences, past, present and to come. And yet I may live and die a true and perfect member of his holy Catholic Church without which I believe there is no salvation for me […].[1]

Born in Lincolnshire in 1543, he was a pupil and friend of the English organist and composer Thomas Tallis († 1585), organist at Lincoln Cathedral (1563) and gentleman of the Chapel Royal (1570); from 1593 he went to live as a country gentleman in a village in eastern England. The differences in the religious sphere that separated him from his contemporaries who switched to Anglicanism didn’t exclude their esteem, the appreciation of his colleagues, and the veneration of his students. By one of the latter, the versatile English composer Thomas Morley († 1603), he is called “my loving Maister [sic], never without reverence to be named of the musicians.”[2] His vast compositional corpus, characterized by versatility, fecundity, feeling, and technical excellence, includes Catholic sacred vocal music, sacred and secular English vocal music, and instrumental music (especially for the virginal, a small harpsichord very popular in Elizabethan England).

Let us dwell briefly on the three Masses composed by Byrd, for 4 voices SATB, for 3 voices STB and for 5 voices SATTB, and published respectively in 1592-93, in 1593-94 and in 1594-95.[3]

It is music written for an intimate, secret setting, for country houses, intended for performance by a small choir of able amateurs and for hearing by a small assembly, all willing to take the risk of participating in such liturgies, which were illegal and punishable in many cases with life imprisonment and even the death penalty.

William Weston († 1615), a Jesuit missionary, describes a gathering dated July 15-23, 1586:

On reaching this gentleman’s house, we were received, as I said before, with every attention that kindness and courtesy could suggest […] [It] possessed a chapel, set aside for the celebration of the Church’s offices. The gentleman was also a skilled musician, and had an organ and other musical instruments, and choristers, male and female, members of his household. During those days it was just as if we were celebrating an uninterrupted octave of some great feast. Mr. Byrd, the very famous English musician and organist, was among the company.[4]

In Masses, Byrd has a concise and very personal style compared to his three illustrious contemporaries, the Roman Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina († 1594), the Flemish Orlando di Lasso († 1594), and the Spanish Tomás Luis de Victoria († 1611). The technique varies: the Kyrie of the Mass for 4 voices is full of imitations, while that of the Mass for 3 voices is articulated through a persistent litany. The melodies are all original, almost audacious: they are never based on Gregorian chant or on well-known motets, as often happens especially in Palestrina’s parody masses. Another original aspect of Byrd’s Masses is the structure in the long movements of the Gloria and the Credo: the former has a subdivision to the words Domine filii, before the usual Qui tollis; the latter has two subdivisions to the words Qui propter, instead of the usual Crucifixus, and Et in Spiritum Sanctum.

Maybe Byrd’s sacred music doesn’t enrapture us and doesn’t make us feel, like that of that man of the Church, that perfect interpreter of the liturgy that was Palestrina, the inexpressible sweetness of the happiness of heaven, of the divine beatitude. But surely Byrd’s sacred art is modeled on the life of the words he sets to music. In the dedication with which Byrd offers Lord Northampton his first book of Gradualia (1605), he says that

there is a certain hidden power, as I learnt by experience, in the thoughts underlying the words themselves; so that, as one meditates upon the sacred words and constantly and seriously considers them, the right notes in some inexplicable manner, suggest themselves quite spontaneously.

[1] B. C. L. KEELAN, The Catholic Bedside Book, New York 1953, p. 421.

[2] T. Morley, A plaine and easie introduction to practicall musicke, London 1597, p. 115.

[3] P. CLULOW, Publication Dates for Byrd’s Latin Masses, in Music and Letters 47, Oxford University Press, 1966, pp. 1–9.

[4] W. WESTON, The autobiography of an Elizabethian, London 1955, pp. 70-71, 76-77.