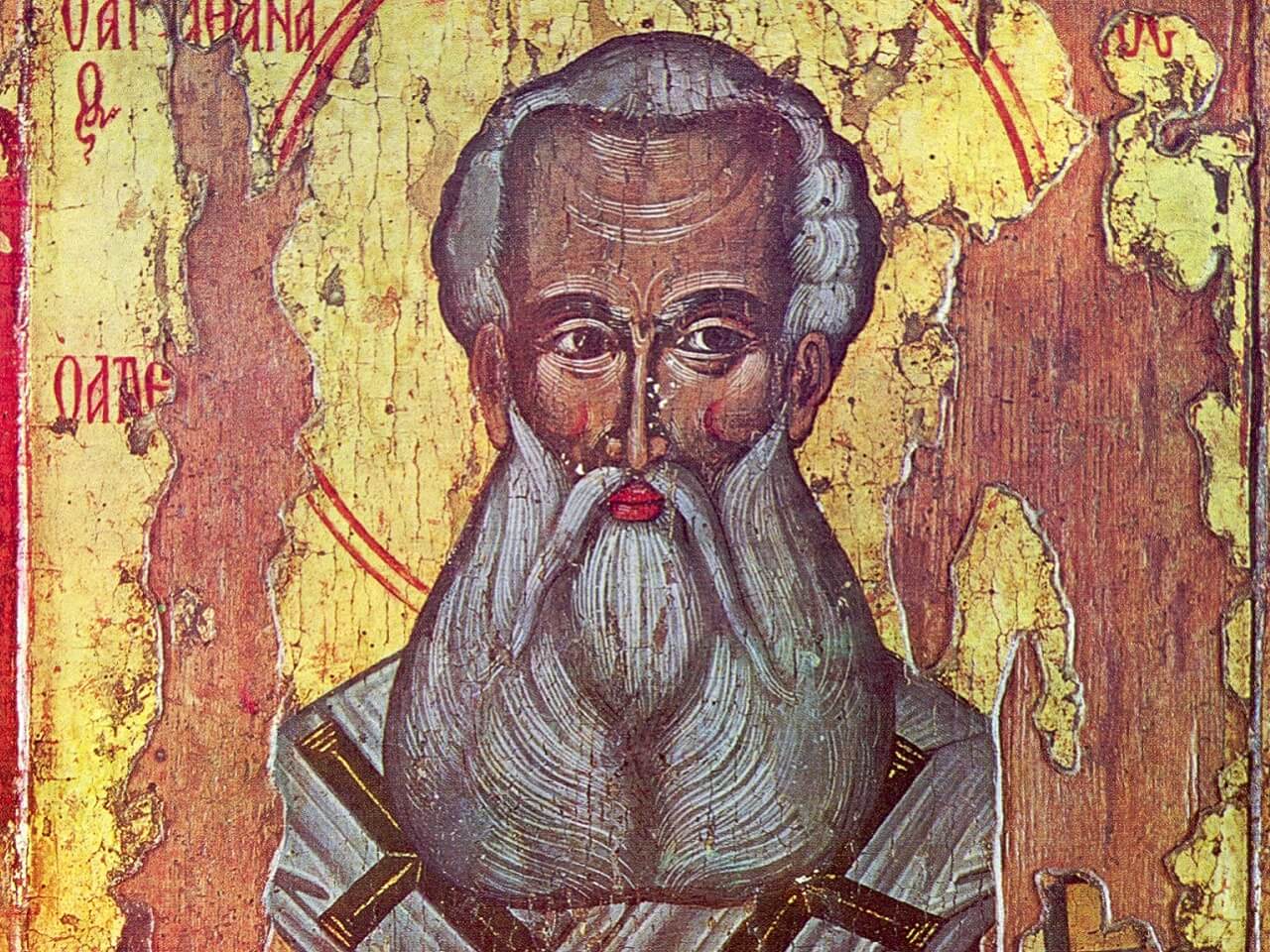

Today we commemorate the 1650th anniversary of the blessed death, which took place on May 2, 373, of the bishop of the Catholic resistance to the Arian heresy, which at that time threatened faith in Christ: St. Athanasius of Alexandria.

This great Father of the Church was born about 75 years earlier in Alexandria in Egypt. He took part in the first Ecumenical Council (Nicæa, 325) as a deacon and secretary to his bishop, whom he succeeded on June 7, 328 by the will of the people. Here he defended, against the heresies of the Alexandrian priest Arius († 336), the consubstantiality of the Logos, the Son who is “of the same substance” as the Father, He is God from God, He is His substance. For this reason Athanasius had a life full of troubles and only after seventeen years he was able to return to his Egyptian metropolis. This great saint is the author of a very successful Life of Anthony, of several Apologies, of three orations against the Arians, of the treatises De incarnatione Verbi and De decretis Nicænis, of the Historia Arianorum ad monachos and of numerous letters.

Among the latter we find the marvelous Letter to Marcellinus on the interpretation of the Psalms (here in the original Greek), a real “handbook” for the use of the book of 150 psalms of the Old Testament or Davidic psalter. In it the champion of the faith professed in Nicæa teaches with great wisdom the aptitude necessary for singing psalms, in order to please God and benefit the faithful who listen.

Let’s propose in summary form the message of the Patriarch of Alexandria’s Letter, in the translation of A Religious of C.S.M.V.[1] “Each book of the Bible has, of course, its own particular message. […] By contrast, the Psalter is a garden which besides its special fruit, grows also some those of all the rest” (§ 2). Some examples: “the creation of which we read in Genesis is spoken of” in Psalms 19 and 24; “the exodus from Egypt, which Exodus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy record, is fitly sung in Psalms” 78, 114, and 105-106; “as for the tabernacle and the priesthood” (§ 3) there is Psalm 29; “the doings of Joshua, the son of Nun, and of the Judges also are mentioned, this time in Psalm 105”; “In the same way, Psalm 20 has the kings in mind”; psalms 126 and 122 speak “of that which Esdra tells” (§ 4); almost every Psalm refers to the Prophets (§ 5); “and, so far from being ignorant of the coming of Messiah, he makes mention of it” in Psalms 45 and 87 (§ 6); of his humanity in Psalms 2 and 22 (§ 7); “The Psalter further indicates beforehand the bodily Ascension of the Saviour into heaven” in Psalms 24, 47, 110 (§ 8), and so on.

However,

the Psalter has a very special grace, a choiceness of quality well worthy to be pondered; […] it has this peculiar marvel of its own, that within it are represented and portrayed in all their great variety the movements of the human soul. It is like a picture, in which you see yourself portrayed, and seeing, may understand and consequently form yourself upon the pattern given. Elsewhere in the Bible you read only that the Law commands this or that to be done […], [the announcement of the] Savior’s coming […] but in the Psalter […] you find depicted […] all the movements of your soul.

The Psalter teaches us how we should repent, persevere, hope, give thanks; from the Psalm we also learn what those who flee and are persecuted must say, how to praise and bless the Lord (§ 10).

“In the other books of Scripture” the reader or listener feels alien compared to “holy men”; in the Psalms instead he is the character (§ 11).

All of this is the gift give to us by the Savior who became man for our sake. “Before He came among us, He sketched the likeness of this perfect life for us in words, in this same book of Psalms” (§ 13).

“The whole divine Scripture is the teacher of virtue and true faith, but the Psalter gives a picture of the spiritual life.” The Psalms are divided into various genres: “some are in narrative form; some are hortatory, […] some are prophetic; […] some, in whole or part, are prayers to God […]; some are confessions […], some denounce the wicked […]; and many more, voice thanksgiving, praise, and jubilation” (§ 14). In paragraphs 15-26 of the Letter we find “the reflection of our own soul’s state” (§ 15).

Furthermore, the holy Doctor of the Church doesn’t “omit the reason why words of this kind should be not merely said, but rendered with melody and song.” It is not “just to make them more pleasing to the ear!” (§ 27). First of all, the very honor of God demands it. Secondly, singing expresses the harmony of the soul.

It is in order that the melody may thus express our inner spiritual harmony, just as the words voice our thoughts, that the Lord Himself has ordained that the Psalms be sung and recited to a chant. […] And if there is in the words anything harsh, irregular or rough, the tune will smooth it out, as in our own souls also sadness is lightened as we chant (§ 28).

Undoubtedly, Athanasius adds, one must sing the Psalms wisely, please God and benefit the listeners, as “the blessed David” did “when he played to Saul” (§ 29).

The holy Alexandrian bishop draws our attention to fidelity to text:

No one must allow himself to be persuaded, by any arguments what-ever, to decorate the Psalms with extraneous matter or make alterations in their order or change the words them-selves. They must be sung and chanted in entire simplicity, just as they are written, so that the holy men who gave them to us, recognizing their own words, may pray with us, yes and even more that the Spirit, Who spoke by the saints, recognizing the selfsame words that He inspired, may join us in them too. For as the saints’ lives are lovelier than any others, so too their words are better than ever ours can be, and of much more avail, provided only they be uttered from a righteous heart (§ 31).

The Spirit will gradually lead the one who prays from dissonance to consonance (§ 29) and will change him: man who has become like a psaltery, docile to the plectrum of the Spirit, is subject in all his limbs and movements to serve the will of God (§ 28).

With these premises it is not surprising what is reported by Sozomen († 420), the Greek ecclesiastical historian. He writes what the impressive effect of the people, acclaiming in church the refrain of Psalm 118 (His mercy endures forever) produced in the lackeys of Arius: shocked by the eurythmy of the singing, by the lively passion and feeling with which the faithful sang, they didn’t have the courage to arrest Bishop Athanasius.[2]

[1] In St. Athanasius on the Incarnation (St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, Crestwood NY 1982), pp. 97-119.

[2] J.P. MIGNE, Patrologia Græca, Vol. 67, col. 1048.