As could be expected in any age, no matter how rotten the circumstances, the Lord continues to raise up men and women who have the traits of holiness. Two well-known examples are Blessed Chiara Badano (1971–1990) and Blessed Carlo Acutis (1991–2006). Does the fact that they lived exclusively within the sphere of the Novus Ordo count as a refutation of traditionalists, who maintain that the reformed—or rather, deformed—liturgy is unhealthy for one’s spiritual life?

No, it does not, any more than the salvation of those who are not visibly members of the Catholic Church would overturn the dogma extra ecclesiam nulla salus. In Reclaiming Our Roman Catholic Birthright, I make this observation:

That there have been a few saints after and under the Novus Ordo does not prove that it is equal in its sanctifying power to the traditional Latin Mass, just as the fact that some demons can be expelled by the new rite of exorcism does not contradict the general agreement of exorcists that the traditional Latin rite of exorcism is far more effective. At most, such things prove that God will not be thwarted by churchmen or their reforms. As theologians teach, God is not bound to His ordinances: He can sanctify souls outside of the use of sacraments, even though we are duty-bound to use the sacraments He has given us. Analogously, He can sanctify a loving soul through a liturgy deficient in tradition, reverence, beauty, and other qualities that ought to belong to it by natural and divine law, although in the normal course souls ought to avail themselves of these powerful aids to sanctity. (p. 12)

Two further thoughts suggest themselves.

First, it is surely possible that a layman might become very holy in a prison camp in Siberia, without access to sacraments at all. It is possible that a priest-prisoner in that camp might become very holy, celebrating Mass with a scrap of bread and a thimble of vinegar. This is not, however, the norm that God intends for us, and it’s likely that the prison camp treatment would not develop the sanctity of most people. Some would be led to despair, some to madness, some to apostasy, and some to bestial behavior. Let’s not forget that for every martyr of Christianity under the ancient Romans, there were many others who apostatized, handed over the sacred books, burnt a pinch of incense to the divine Emperor.

Second, we need to take a longer view and ask what fruits of sanctity have been produced over the 50+ year period of the liturgical reform. Surely, there have been some good fruits, for any time people attempt to live by the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity, such fruits will not be lacking. But does the past half-century have the wherewithal to compare to any other 50-year period in the Catholic Church, if we measure it by the lives of the saints and masterworks of fine Christian art (the two criteria Joseph Ratzinger identified as unarguable proofs of the Gospel’s truth)? The answer is plain for all to see. The age of liturgical reform is characterized by an unprecented apostasy from the Faith, a massive hemorrhaging of churchgoers, a dissipation and dissolution of Catholic identity that exceeds even the damage done by the Protestant Revolt. The trend in the West, where the Rhine mingled with the Tiber, has been steadily downward—except in the traditionalist movement.[i]

Let me point to a different comparison: democracy in the modern sense has been around for about 250 years. So far, almost nobody with a reputation for sanctity has emerged from its ruling classes. Contrast that with the European monarchies of old: scores and scores of saints. Granted, it’s a bit of an apples and oranges comparison, but the point is that the old Mass is the healthy environment of Christendom, and the new Mass is the unhealthy environment of Bugniniville (which could never compete with Margaritaville). There have been many great fruits from the one, neither so many nor so great from the other. We can expect to see contrasts similiar to those between pre-democratic, hierarchical, traditional societies and democratic, egalitarian, secular societies.

If someone comes back with: “Okay, then: you trads had better be producing some impressive saints!,” I would respond: “Yes, we’re working on it—but let’s not forget that, even if our positive numbers are growing disproportionately—number of marriages, baptisms, priestly and religious vocations, etc.), we represent something like 1–5% of the Catholic population. So at least be fair about making statistical adjustments.”

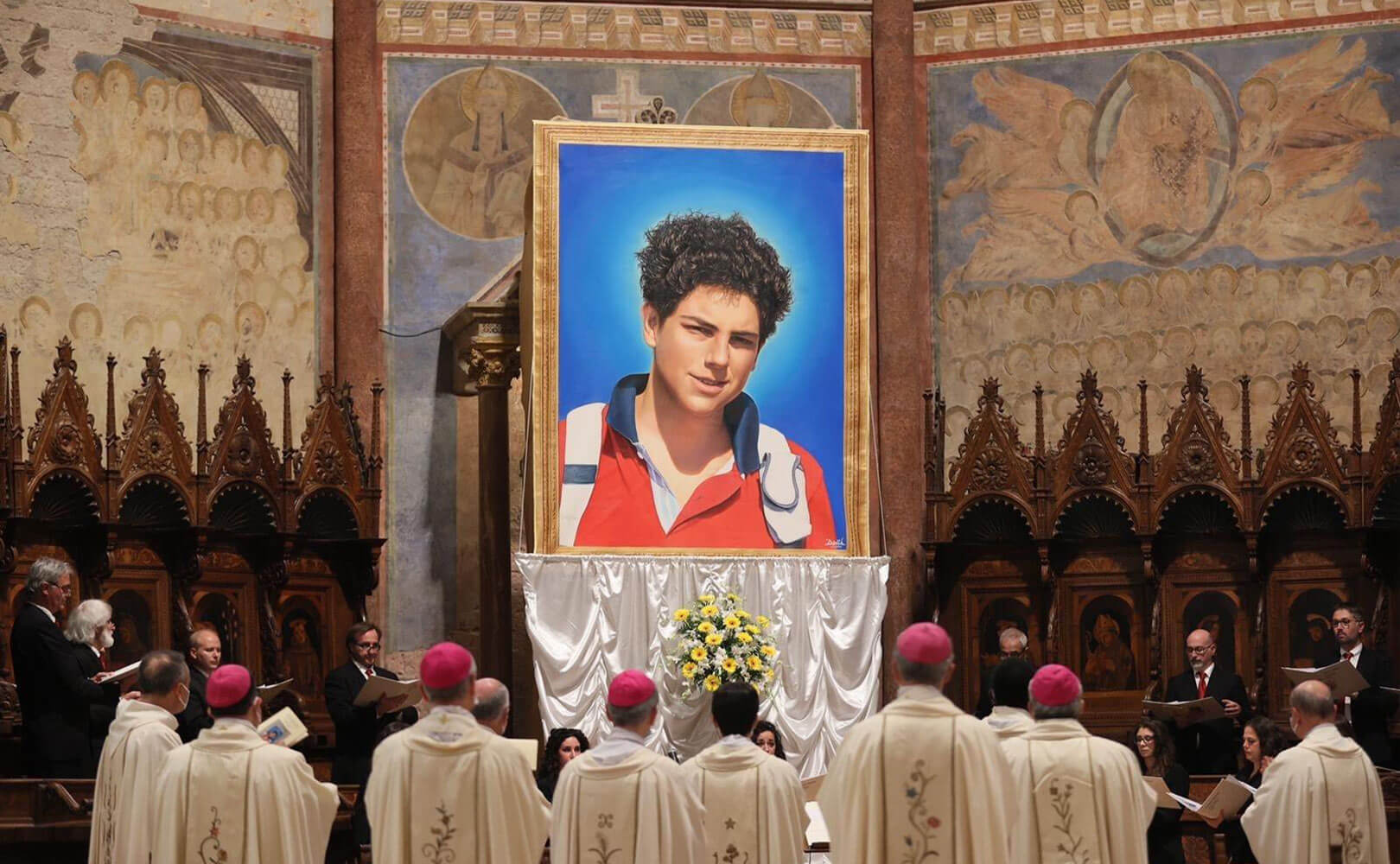

From a cursory reading of the life of the new beatus Carlo Acutis,[ii] one can say that he responded with tremendous generosity to the divine call. He was deeply devoted to Eucharistic Adoration, which has the power to transform lives. There is no particular reason to be troubled about his beatification or his veneration; it is not saddled with the many problems that, for example, Paul VI’s beatification and canonization labor under. Like the Siberian prisoner, Carlo made the most of the Real Presence of the Lord, amidst the shreds of tradition and scraps of meaning that the modern Italian Church could give him. In spirit, he was raised above the limitations of his time and place. If Bishop Athanasius Schneider is pleased to invoke his intercession, so am I.

Nevertheless, we should be wary about the tendency of the present-day Vatican to utilize God’s gifts for its own perverse ends. Beatifications and canonizations have become tools wielded by the modernist agenda. We must distinguish between what the life of a saint actually exemplifies, and what the Vatican has superimposed on it. For example, a Zenit article in French connects Carlo’s particular charisms with Pope Francis’s encyclicals Laudato Si’ and Fratelli Tutti, because, don’t you know, Blessed Carlo loved animals and nature, and wanted to help the homeless. It’s a perfect opportunity to make Carlo into a poster-child of the Francis era.

In general, I am very sympathetic to the idea of normally waiting fifty years (or, in any case, a good long while) to initiate a cause of beatification or canonization, let alone complete it. It is wise to “let the dust settle” and see, among other things, if there is continuing evidence of a strong popular cultus of the figure in question. The lack of popular veneration—or the need to pump it up artificially, as if one is campaigning for political candidates—is one of the most troubling aspects of recent beatifications and canonizations. It’s as if the Church hierarchy no longer trusts that the Christian faithful by an instinct of faith can recognize and respond to holiness when they encounter it. Come to think of it, the Vatican has good reason to be nervous, for if they let the sensus fidelium have its way, Archbishop Lefebvre would end up on the desk of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. He has garnered ten thousand times more popular veneration than Paul VI, who condemned him, ever has or ever will.

A further and more wide-ranging note of caution is in order. When it comes to saints who had to live under the new cultural barbarism of our times, we have to be careful not to “canonize” along with their sanctity something incidental about their modern lives. This will happen quite often from this point forward. “Oh, Blessed Bobby was so into pop music! Isn’t it great that pop music is part of sanctity now, and it just doesn’t matter what you listen to or dance to?” or “Saint Suzy just loved to go around in sweat pants and a fluorescent pink T-shirt! I guess it doesn’t really matter how you dress anymore when it comes to being a saint.” One can imagine all kinds of scenarios and false inferences like these.

The way to navigate this matter—and, to be fair, it has parallels in every age of the Church; for instance, the saints of the Dark Ages had remarkably bad hygiene, but no one, to my knowledge, suggests we should imitate them in that regard—is to remember the relationship, and the distinction, between reason and faith, nature and grace. A man notable for holiness may not be notable for good arguments in theology; a woman of indisputable sanctity may not have good taste in art. As disciples of the Church’s Common Doctor, St. Thomas Aquinas, we have to be able to make distinctions and imitate what deserves imitating, while dismissing what is pardonable or ignoring what is better off ignored.

Put it this way: if one had to make a choice, it would be better to be devoted to prayer and yet listen to mediocre music or dress in a mediocre way than to be a cunning egotist who has impeccable taste in cufflinks and bowties; but it is best to be both holy and cultivated, both pious and intelligent, because that represents a fuller perfection of humanity as God intended it. Thanks be to God, we can achieve beatitude in spite of certain defects, but that doesn’t make the defects admirable or worthy of imitation.

The foregoing would also tie in to the question of how we are supposed to depict saints of recent decades in statuary, stained glass, or paintings. I would strongly maintain that it would be a frightful mistake to put them in jeans and sneakers, sporting an acoustic guitar. This is like low Christology: Jesus with the baseball cap, ready to help Jimmy hit the line drive. No. When we depict the saints, we are depicting those who have gone before us into glory. They are part of the cloud of heavenly witnesses, not still at home doing the same old stuff. This is the difference between a photo album of the past and an icon opening to the eschatological kingdom. A certain stylization is required for any saint, but especially for those of which we have photos. I have seen successful examples of modern saints like St. Thérèse, St. Maximilian Kolbe, and St. John Henry Newman, but I have also seen absolutely deplorable ones. David Clayton has written insightfully on this question, as have other master iconographers.

These issues need to be discussed charitably and patiently, out in the open. Ever since John Paul II, there has been a concerted effort to beatify and canonize contemporary figures as rapidly as possible. While there need not be malicious intent behind that trend, it will inevitably result more and more in the perception, no doubt desired by the propagandists, that the current ecclesiastical situation is “fine,” as it still produces saints! In reality, it is God alone who produces saints from the womb of Holy Mother Church. Sometimes the saints are born by a natural birth—traditional catechesis, liturgy, devotions, and theology—and sometimes they are born by emergency C-section, that is, through divine intervention in a situation that would otherwise be hopeless. Just because the latter occurs does not make it normative or optimal.

It is right and just, it always will be right and just, for Catholics to pray and work for the restoration of our tradition, as we ourselves strive to be the saints God is calling us to be.[iii]

NOTES:

[i] It is true that the Church has been growing for decades in Africa and Asia, though one cannot neatly attribute that growth to Vatican II or the liturgical reform.

[ii] One can read about him online in multiple places, e.g., here, here, and here.

[iii] Una versión en español de este artículo ha sido publicada aquí.