Editor’s note: this and related articles have now been published in a book entitled: Disputed Questions on Papal Infallibility (Os Justi Press, 2022).

For part 1 see here.

Question I:

On the Extension and Limits of Papal Infallibility

(Continued)

Article 3

Whether the Infallibility of the Pope Is Limited to the Exercise of His Extraordinary Magisterium?

Objection 1: It seems that the infallibility of the pope is not limited to the exercise of his extraordinary magisterium, but extends also to his ordinary magisterium. For according to the Second Vatican Council, the pope as head of the Church possesses the same infallibility as the whole Church.[1] And the Church is infallible both in her solemn (or extraordinary) judgments and in her ordinary and universal magisterium.[2] Therefore, as Salaverri concludes, the pope must also be infallible both in his extraordinary judgments and in his ordinary magisterium.[3]

Objection 2: Furthermore, as Salaverri points out,[4] the pope possesses the complete fullness of the supreme power of jurisdiction over the Church, which includes the power of the magisterium.[5] But if the pope were not infallible in his exercise of the ordinary magisterium, then he would not possess the complete fullness of magisterial power, since the gift of infallibility would then be more restricted in the pope than in the Church, for the Church is infallible in her ordinary and universal magisterium. Therefore, etc.

Objection 3: Furthermore, according to Fenton,[6] the extraordinary magisterium is exercised only in “solemn” judgments.[7] But the pope is infallible whenever he speaks ex cathedra, and ‘solemnity’ is not one of the conditions required for speaking ex cathedra.[8] Hence, the infallibility of the pope is not limited to “extraordinary” definitions, i.e., those issued with special solemnity, but extends also to “ordinary” ex cathedra definitions.

On the contrary, according to Bishop Gasser’s relatio on papal infallibility: “The pope is only infallible when, by a solemn judgment, he defines a matter of faith and morals for the Church universal.”[9] But a solemn judgment is an exercise of the extraordinary magisterium; hence, the pope is infallible only in his extraordinary magisterium.

I answer that, the infallibility of the pope is limited to the exercise of his extraordinary magisterium. The ordinary and universal magisterium, which is the magisterium of the whole Church dispersed throughout the world, is infallible when it proposes a doctrine of faith or morals “as to be believed as divinely revealed” or “as definitively to be held.”[10] Now it is impossible that the pope should not likewise be infallible when he proposes doctrine in the same way, lest we fall into the error of the Gallicans by attributing greater authority to the Church than to the pope. But when the pope, as head of the universal Church, proposes a doctrine of faith or morals “as to be believed as divinely revealed” or “as definitively to be held,” then he speaks ex cathedra, and this is reckoned as an exercise of the extraordinary magisterium.

According to Pope Pius IX, the distinction between the ordinary and the extraordinary magisterium of the Church is this, that the extraordinary magisterium is exercised in “explicit decrees of ecumenical councils or Roman pontiffs,” while the ordinary magisterium is exercised in the general teaching of “the whole Church dispersed throughout the world,”[11] on account of which the First Vatican Council described the ordinary magisterium as “universal.”[12] The two modes of infallible teaching possessed by the bishops, therefore, pertain to the distinction between the being gathered in council and being dispersed throughout the world; but no such distinction is possible for the singular person of the pope, and so he requires only one mode of infallible teaching.

Reply to Objection 1: To the first it must be said that this argument equivocates on the term “ordinary magisterium,” which means one things when applied to the Church and another thing when applied to the pope. Now the term “extraordinary magisterium” refers unequivocally to the explicit and definitive teaching of the Church—that is, the infallible teaching of the Church that is tangibly enshrined in public documents of the supreme magisterium. But because the extraordinary magisterium has two essential characteristics (namely, that it is both explicit and definitive), two essentially different forms of teaching can be contrasted against it and each will appear to be “ordinary” by comparison, though in different ways. First, and more properly, the term “ordinary magisterium” refers to the equally definitive, but not equally explicit teaching of the Church—that is, to the infallible teaching of the Church that is not found in explicit decrees of popes or councils but is gathered instead from all the sources of theology, and especially from the plain sense of Scripture, the consensus of the Church Fathers, the consensus of Catholic theologians, the consensus of the bishops, or the consensus of the faithful.[13] Secondly, however, the term ‘ordinary magisterium’ is also sometimes used to refer to the equally explicit, but not equally definitive teaching of the pope or the college of bishops,[14] which is more properly called the “authentic magisterium” of the pope or bishops.[15] But since “ordinary” in this case simply means “non-definitive” or “non-infallible,” it is impossible for the pope to speak infallibly through his “ordinary” magisterium.

Reply to Objection 2: To the second it must be said that the reason why the pope is not infallible in his ordinary magisterium is not because of a defect of magisterial power, but precisely on account of its fullness. The infallibility of the ordinary and universal magisterium of the Church arises from the consensus of individually fallible teachers proposing a doctrine of faith or morals as definitively to be held. But when the pope proposes a doctrine of faith or morals as definitively to be held, his teaching is infallible of itself and not by the consensus of the Church.

Reply to Objection 3: To the third it must be said that, although it is true that solemnity is not a condition for infallible papal definitions, nevertheless the term “solemn” is not used restrictively in the expression “solemn judgment,” as the objection supposes, but rather descriptively. That is, every infallible definition of doctrine, whether issued by pope or council, is intrinsically solemn, whether or not it is phrased in especially solemn language or issued with special solemnity of pomp and circumstance. There can be no ex cathedra definition which is not by that very fact a solemn judgment of the extraordinary magisterium.

Article 4

Whether the Pope Is Able to Speak Infallibly When He Confirms or Reaffirms a Doctrine Already Taught Infallibly by the Ordinary and Universal Magisterium?

Objection 1: It seems that the pope is not able to speak infallibly when he confirms or reaffirms a doctrine already taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium. For according to the doctrinal commentary of the CDF on the concluding formula of the Profession of Faith: “Such a doctrine can be confirmed or reaffirmed by the Roman Pontiff, even without recourse to a solemn definition. . . . The declaration of confirmation or reaffirmation by the Roman pontiff in this case is not a new dogmatic definition, but a formal attestation of a truth already possessed and infallibly transmitted by the Church.”[16] Therefore, such acts of confirmation or reaffirmation of existing Catholic doctrine are not infallible.

Objection 2: Furthermore, according to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, commenting on Ordinatio Sacerdotalis: “The Pope is not proposing any new dogmatic formula, but is confirming a certainty which has been constantly lived and held firm in the Church. In the technical language one should say: here we have an act of the ordinary magisterium of the Supreme Pontiff, an act therefore which is not a solemn definition ex cathedra.”[17] But if Ordinatio Sacerdotalis belongs to the ordinary papal magisterium precisely because it does not propose any new dogmatic formula, then the pope is only able to speak infallibly when defining new dogmas; and not, therefore, when confirming or reaffirming what has already been taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium.

Objection 3: Furthermore, according to Archbishop Tarcisio Bertone: “If we were to hold that the Pope must necessarily make an ex cathedra definition whenever he intends to declare a doctrine as definitive because it belongs to the deposit of faith, it would imply an underestimation of the ordinary universal magisterium, and infallibility would be limited to the solemn definitions of the pope or a council.”[18] Therefore, etc.

Objection 4: Furthermore, the extraordinary magisterium of the pope is exercised in the act of solemn judgment, by which he settles controversies of faith. But if the pope confirms or reaffirms an existing Catholic doctrine, then he does not settle a controversy of faith, and therefore does not exercise the extraordinary magisterium. And he is only infallible in his extraordinary magisterium, as shown above. Therefore, etc.

Objection 5: Furthermore, it would be unnecessary to define infallibly a doctrine that has already been taught infallibly by the Church; and it would be unfitting for papal infallibility to be exercised unnecessarily; therefore, we ought not to suppose that the pope speaks infallibly when he confirms or reaffirms a doctrine already infallibly taught by the Church.

On the contrary, according to Pope Pius XII, the Assumption of Mary was already a dogma infallibly taught by the ordinary and universal magisterium before he proceeded to confirm it as such by a solemn definition.[19]

I answer that, the pope is able to speak infallibly not only when he defines new dogmas, but also when he definitively confirms or reaffirms a doctrine already infallibly taught by the Church. For the purpose of the charism of infallibility bestowed on the pope by Christ is so that all Christ’s faithful would be able to know with certainty what they ought to believe in order to be saved. But doubts may arise in the Church not only with regard to legitimately disputed questions, but also when the established teaching of the Church is obscured by heresies and errors. And indeed, the need for an infallible judgment is all the more urgent in the latter case. Thus the purpose of infallibility would be frustrated if the pope were not able to issue an infallible judgment by which he confirms or reaffirms existing Catholic doctrine.

Moreover, it is clear from history that the Church is able to pronounce solemn and infallible definitions by which she confirms or reaffirms doctrines already taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium. For the Council of Nicaea solemnly defined the co-equal divinity of Christ, which had been infallibly taught by the ordinary and universal magisterium of the Church from the beginning, according to the words of Christ: “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). Likewise, the Council of Trent defined the necessity of good works for salvation, which had always been taught infallibly by the Church, according to the words of St. James: “You see then that a man is justified by works, and not by faith alone” (Jas 2:24). But in order to avoid falling into the error of the Gallicans, we must hold that the charism of infallibility is not more restricted in the pope than in the Church, as said above. Therefore, the pope is able to pronounce a solemn and infallible definition by which he confirms or reaffirms a doctrine already taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium, as Pope Pius XII did when he defined the dogma of the Assumption.

Reply to Objection 1: To the first it must be said that this doctrinal commentary carries no properly juridical authority, as shown above. So it is permissible to hold that the commentary simply errs on this point. Or perhaps one could also say that the commentary does not entirely exclude the possibility of a solemn definition confirming or reaffirming the infallible teaching of the Church, since it says only that this can be done without a solemn definition, thus leaving open the possibility that it could also be done with a solemn definition.

Reply to Objection 2: To the second it must be said that there are no grounds for such a restriction of the extraordinary magisterium to the defining of new dogmas. This error seems to have arisen from a partial reading of Cardinal Louis Billot, who describes an ex cathedra definition as a “new doctrinal judgment” and contrasts this against the way in which papal encyclical letters typically instruct the faithful about things already within the teaching of the Church.[20] However, Billot also proceeds to say that the term “defines,” as it is used at Vatican I in the definition of papal infallibility, “is to be taken indiscriminately, whether about a thing never before defined, or about a thing already previously contained explicitly in the rule of the ecclesiastical magisterium, confirmed again by a new sentence and a new judgment of the pope; just as we see practiced in the ecumenical councils with regard to the appearance of new errors or the return of old ones.”[21] Hence, the solemn definition of a truth already infallibly taught by the Church is indeed a new judgment, but the only thing new about it is the new act of reaffirming the same doctrine.

Reply to Objection 3: To the third it must be said that this argument would hold only if the same doctrine could not be infallibly taught more than once, but there is no reason to suppose such a limitation. And in fact, many doctrines have been taught infallibly more than once. For example, that the sacred Scriptures are divinely inspired has always been taught infallibly by the ordinary and universal magisterium, according to the words of St. Paul: “All Scripture is inspired by God” (2 Tim 3:16); and yet this was solemnly defined both at Florence and at Trent, according to the words of Pope Leo XIII: “This is the ancient and unchanging faith of the Church, solemnly defined in the Councils of Florence and of Trent.”[22]

Reply to Objection 4: To the fourth it must be said that the solemn judgments of popes and ecumenical councils are always sufficient to settle controversies of faith, but it is not necessary that there be an actual controversy of faith in order for a solemn judgment to be given. According to Bishop Gasser’s relatio, the forty-seventh proposed emendation to the text of the definition of papal infallibility had to be rejected for this reason: “The reverend Father appears to restrict pontifical infallibility only to controversies of faith, whereas the Pontiff is also infallible as universal teacher and as supreme witness of tradition, the deposit of faith.”[23]

Reply to Objection 5: To the fifth it must be said that this objection neglects the essentially pastoral purpose of the magisterium. As Joseph Kleutgen says:

Something can be universally taught and believed in the Church as revealed truth, and therefore the error opposing it can be rejected with certainty as heretical, and yet a judgment of the Church can still be necessary if the innovators succeed in winning a following, or in seducing even a single prominent member of the Church, or other men of great prestige, such that it is slightly doubtful, especially for the multitude of the faithful, upon which side the truth lies.[24]

Solemn judgments that confirm or reaffirm existing Catholic doctrine may not be necessary for the advance of sacred theology; but they are often very necessary for the salvation of souls, and that is the primary purpose of the magisterium.

Article 5

Whether the Infallibility of the Pope Is Limited to Defining Dogmas of Divine and Catholic Faith?

Objection 1: It seems that the infallibility of the pope is limited to defining dogmas of divine and Catholic faith—that is, to the primary object of the magisterium. For according to Joseph Fessler, in his book on the infallibility of the pope, for which he received a personal letter of thanks from Pope Pius IX, the pope is infallible only when he defines truths as divinely revealed or when he condemns errors as heretical,[25] both of which pertain exclusively to the primary object of the magisterium.

Objection 2: Furthermore, according to Bishop Gasser’s relatio, Vatican I left the question of the secondary object of infallibility in the same state in which it was before,[26] and this was a state of free theological opinion.[27] Hence, it cannot be conclusively asserted that papal infallibility extends beyond the definition of dogma or the condemnation of heresy.

Objection 3: Furthermore, the teaching of the Second Vatican Council is commonly held to be non-infallible precisely because it did not define any new dogmas or condemn any errors specifically as heretical.[28] And the infallibility of the pope is the same as that of the Church, as said above. Therefore, etc.

On the contrary, according to the CDF it is a matter of Catholic doctrine that “the infallibility of the Church’s magisterium extends not only to the deposit of faith,” which is the primary object of the magisterium, “but also to those matters without which that deposit cannot be rightly preserved and expounded,”[29] which refers to the secondary object of the magisterium.

I answer that, the pope is able to speak infallibly not only in defining divinely revealed truths as dogmas of divine and Catholic faith, but also in defining matters of faith or morals that are necessarily connected to divine revelation.

Here it should be noted that the primary object of the magisterium comprises every doctrine directly revealed by God and contained in the deposit of faith—namely, in Scripture or Tradition. Such doctrines can be infallibly defined by the pope as dogmas which must be believed by divine and Catholic faith (de fide credenda), the obstinate doubt or denial of which constitutes heresy.[30] Such dogmas can also be defined negatively by the definitive condemnation of heresy.

The secondary object of the magisterium comprises those truths pertaining to faith or morals that are not directly revealed, but are intrinsically connected to divine revelation by a logical or historical relationship and which are required for inviolately preserving and faithfully expounding the deposit of faith.[31] Common examples of truths contained in the secondary object of the magisterium are philosophical truths presupposed to divine revelation, such as the existence of God, the immortality of the human soul, and the mind’s ability to know truth with certainty; theological conclusions that follow logically from divine revelation by the aid of natural reason; dogmatic facts, such as the legitimacy of an ecumenical council or the validity of a papal election; and the canonization of saints, which will be treated below. Such truths can be infallibly defined by the pope as doctrines which must be held definitively (de fide tenenda). Although the denial of such doctrines would not constitute heresy in the strict sense, the doctrinal commentary of the CDF on the Profession of Faith says that, “Whoever denies these truths would be in a position of rejecting a truth of Catholic doctrine and would therefore no longer be in full communion with the Catholic Church.”[32] Such truths of Catholic doctrine can also be defined negatively by the definitive condemnation of an error as false or proximate to heresy.

The extension of infallibility to the secondary object of the magisterium is taught by the Second Vatican Council, which says: “And this infallibility with which the divine Redeemer willed his Church to be endowed in defining doctrine of faith and morals, extends as far as the deposit of revelation extends, which must be guarded inviolately and expounded faithfully.”[33] For according to the Theological Commission’s official explanation of this text: “The object of the infallibility of the Church, thus explained, has the same extension as the revealed deposit; and therefore it extends to all those things, and only to those things, which either directly pertain to the revealed deposit itself, or which are required for the same deposit to be inviolably guarded and faithfully expounded.”[34] And if the infallibility of the Church extends to the secondary object of the magisterium, then so does the infallibility of the pope. For the pope possesses the very same infallibility as that possessed by the Church, as shown above.

Reply to Objection 1: To the first it must be said that a semi-official letter of approbation for Fessler’s work as a whole does not necessarily imply an endorsement of every claim made within the work. And Bishop Gasser’s relatio explicitly denies that papal infallibility is limited to the definition of dogma and the condemnation of heresy in the way that Fessler would have it:

The Deputation de fide is not of the mind that this word [‘defines’] should be understood in a juridical sense (Lat. In sensu forensi) so that it only signifies putting an end to controversy which has arisen in respect to heresy and doctrine which is properly speaking de fide. Rather, the word “defines” signifies that the pope directly and conclusively pronounces his sentence about a doctrine that concerns matters of faith or morals and does so in such a way that each one of the faithful can be certain of the mind of the Apostolic See, of the mind of the Roman pontiff; in such a way, indeed, that he or she knows for certain that such and such a doctrine is held to be heretical, proximate to heresy, certain or erroneous, et cetera, by the Roman pontiff. Such, therefore, is the meaning of the word “defines”.[35]

Reply to Objection 2: To the second it must be said that the question left unsettled by Vatican I was not whether the infallibility of the pope extends to the secondary object, but rather whether this secondary extension of infallibility is itself a dogma or “merely” theologically certain. This indeed remains an open question. But there can be no doubt that the extension of papal infallibility to the secondary object of the magisterium is at least a theologically certain conclusion, and not merely a matter of theological opinion. Moreover, the constant consensus of Catholic theologians regarding the certitude of this doctrine is sufficient evidence that it is to be held definitively in virtue of the infallible teaching of the ordinary and universal magisterium.

Reply to Objection 3: To the third it must be said that this common opinion about Vatican II is not well-founded. It appears to arise from three sources. First, there is the example of prominent authors such as Fessler who arbitrarily limit papal infallibility to the primary object of the magisterium, as shown above. Second, there is the wording of the 1917 Code of Canon Law, which said: “Nothing is to be understood as dogmatically declared or defined unless this is clearly manifested.”[36] Now the word “dogmatically” can be used in a broad sense to mean something like “fixedly” or “irreformably,” but it also has a narrower meaning which refers exclusively to the primary object of the magsterium. And so it seems to have been interpreted by many. But this is corrected in the 1983 Code of Canon Law, which substitutes ‘infallibly’ for ‘dogmatically’ so that the canon now reads: “Nothing is to be understood as infallibly defined unless this is manifestly the case.”[37] Finally, there are the words of Pope Paul VI, saying that the council “did not wish to issue extraordinary dogmatic pronouncements,”[38] and again, that it “avoided giving solemn dogmatic definitions backed by the infallibility of the Church’s magisterium,”[39] and “avoided pronouncing in an extraordinary way dogmas endowed with the note of infallibility.”[40] But if Paul VI is using the terms “dogma” and “dogmatic” in the broader sense of “definitive,” then we cannot infer from his words any restriction of infallibility to the primary object of the magisterium. And if he is using them in the stricter sense, then we can only infer that Vatican II did not in fact infallibly define any dogmas (de fide credenda), but not that it could not or even did not define any truths of Catholic doctrine (de fide tenenda).

Article 6

Whether the Infallibility of the Pope Extends to the Canonization of Saints?

Objection 1: It seems that the infallibility of the pope does not extend to the canonization of saints. For according to John Lamont, in order to teach infallibly, the pope “must assert that his teaching is a final decision that binds the whole Church to believe in its contents upon pain of sin against faith.”[41] But in the formula of canonization, as Lamont says:

There is no mention of teaching a question of faith or morals, no requirement that the faithful believe or confess the statement being proclaimed, and no assertion that a denial of the proclamation is heretical, subject to anathema, or entails separation from the unity of the Church. The absence of these condemnations is itself an absence of the condition of the intent to bind the whole Church in the sense required for an infallible teaching, because these assertions are what constitute binding the Church in this sense.[42]

Objection 2: Furthermore, the infallibility of the Church extends only to matters of faith or morals that are either contained in divine revelation or so closely connected with the deposit of faith that “revelation would be imperiled unless an absolutely certain decision could be made about them.”[43] Now the sanctity of any particular post-apostolic Christian cannot possibly be contained in divine revelation; nor is it necessarily connected with divine revelation unless “the doctrine of a particular saint has been so extensively adopted by the infallible teaching of the Church that denial of his sanctity would cast doubt upon the teachings themselves” or unless “devotion to a saint has been so widespread and important in the Church that the denial of that individual’s sanctity would cast doubt upon the role of the Holy Spirit in guiding the Church.”[44] But these conditions are not realized in many canonizations. Therefore, canonizations are not necessarily infallible.

Objection 3: Furthermore, recent changes in the process of examining causes for canonization, such as the abolition of the so-called devil’s advocate and the reduction in the number of miracles required, have considerably lessened the reliability of these examinations, so that even if canonizations used to be infallible, they cannot be so any longer.

Objection 4: Furthermore, in the ceremony of canonization there are prayers for the truthfulness of the decree of canonization, which implies the possibility that the decree could be false.

On the contrary, according to Thomas Aquinas: “The honor we show the saints is a certain profession of faith by which we believe in their glory, and it is to be piously believed that even in this the judgment of the Church is not able to err.”[45]

I answer that, the infallibility of the pope extends to the canonization of saints. To begin with, it is clear that the pope is issuing a solemn judgment as supreme head of the universal Church when he pronounces the typical formula of canonization: “For the honor of the blessed Trinity, the exaltation of the Catholic faith, and the increase of the Christian life, by the authority of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of the holy apostles Peter and Paul, and our own, we declare and define that N. is a saint and we enroll him among the saints, decreeing that he is to be venerated as such by the whole Church.”

Hence, the only question that arises is whether the canonization of saints is a matter of faith or morals. And here it must be said that the canonization of the saints is intrinsically connected with the holiness of the Church, which is one of the essential marks of the Church, and so falls within the secondary object of infallibility. For by the act of canonizing a saint, the pope not only declares that this saint is in heaven, but also establishes the liturgical veneration of this saint, so that the most holy sacrifice of the Mass should henceforth be offered in honor of this saint. But it would be contrary to the holiness of the Church if the whole Church would be obliged to venerate and to offer Masses in honor of a soul not in heaven.

Moreover, according to Salaverri, the infallibility of the pope in canonizing saints has been implicitly defined.[46] For on several occasions, the supreme pontiffs have expressly declared the infallibility of these judgments. For example, Pope Pius XI: “We, as the supreme teacher of the Catholic Church, pronounce infallible judgment with these words . . .”[47] And again: “We, from the chair of blessed Peter, as the supreme teacher of the whole Church of Christ, solemnly proclaim with these words an infallible judgment . . .”[48] Likewise, Pope Pius XII: “We, the universal teacher of the Catholic Church, from the one chair founded on Peter by the word of the Lord, have solemnly pronounced with these words this judgment, knowing that it cannot be wrong . . .”[49] Therefore, although it would not be heretical in the strict sense to deny the infallibility of the canonization of saints, it would be contrary not only to the common teaching of Catholic theologians but also to the express teaching of Popes Pius XI and Pius XII.

Reply to Objection 1: To the first it must be said that the definitive and binding character of the decree of canonization is sufficiently manifest in the formula of canonization through the use of the word ‘definimus’ (‘we define’). Lamont, however, objects that the presence of the word ‘definimus’ in the formula of canonization is not decisive, saying:

Nor can we suppose that the use of the Latin word ‘definimus’ necessarily signifies the act of defining a doctrine of the faith. The word has a more general, juridical sense of ruling on some controversy concerning faith or morals. This general sense was recognized by the fathers of the First Vatican Council, and explicitly distinguished by them from the specific sense of ‘definio’ that obtains in infallible definitions.[50]

But this is almost the complete reverse of the truth. As seen above, the official relatio on infallibility does indeed distinguish between a broader and a narrower sense of the word ‘defines’; but it is the narrower sense which Gasser describes as ‘juridical’ and which he rejects, while affirming that the broader meaning of the word obtains in infallible definitions as noted above (a5 ad 1).[51]

Reply to Objection 2: To the second it must be said that the canonization of every saint is sufficiently connected to divine revelation in precisely the way that the objection maintains on behalf of only some saints. That is, just as the denial of the sanctity of a saint who has already been widely venerated in the Church would cast doubt upon the role of the Holy Spirit in guiding the Church, so also would the denial of the sanctity of one whose veneration has been decreed for the whole Church for the future.

Reply to Objection 3: To the third it must be said that the charism of infallibility rests on the promise of God, not the reliability of the process. As such it guarantees only the truth of the final definition, not the prudence of making it. Just as the pope, when he intends to define a dogma of faith, ought carefully to investigate the sources of revelation in order to be certain of the truth he intends to define, so also, when he intends to canonize a saint, he ought carefully to investigate the sanctity of that person in life and the miracles worked by him after his death. Failure to do so places himself at risk of being directly prevented by divine intervention, but it does not cast doubt on the certainty of the canonization itself.

Reply to Objection 4: To the fourth it must be said that prayers for the truthfulness of the decree are inconclusive since there is nothing unfitting in asking God to do that which he has promised to do.

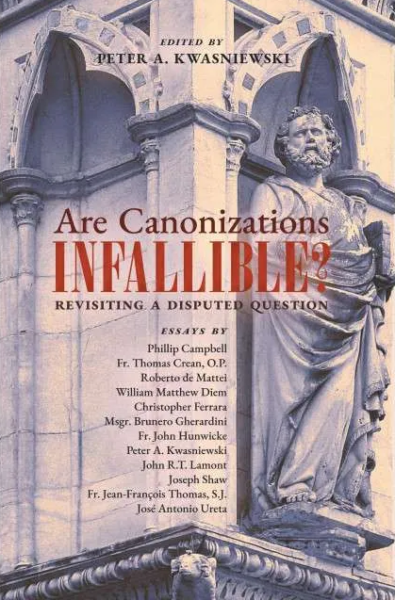

Editor’s note: for more on this disputed question, see this volume edited by our contributing editor, Peter A. Kwasniewski:

Article 7

Whether the Pope Is Able to Speak Infallibly without Explicitly Addressing the Universal Church?

Objection 1: It seems that the pope is not able to speak infallibly when he does not explicitly address his teaching to the universal Church. For as Bishop Gasser’s relatio makes clear, the pope is only said to be infallible when he teaches as supreme head of the Church and “not, first of all, when he decrees something as a private teacher, nor only as the bishop and ordinary of a particular See and province.”[52] But if the pope addresses his teaching only to a part of the Church, then he may be acting only as local bishop of Rome, or Primate of Italy, or Patriarch of the West, and not as head of the universal Church.

Objection 2: Furthermore, according to the definition itself, the pope is only said to be infallible when he defines a doctrine as one that is “to be held by the whole Church,”[53] which he cannot do if he does not address his teaching to the whole Church.

On the contrary, according to Billot: “It is not necessary for a papal document to be materially directed to all the bishops or faithful; it is enough that it pertains to the deposit of faith and there is present the manifest intention of putting an end to doubt by a definitive sentence not subject to further determination.”[54]

I answer that, in order to speak infallibly the pope must be acting as supreme head of the whole Church. This is most clearly manifest when the pope explicitly addresses the whole Church, as he frequently does in his apostolic constitutions and encyclical letters. But this can be made manifest in other ways. For example, in the encyclical letter Commissum Divinitus, which is addressed only to the clergy of Switzerland, Pope Gregory XVI explicitly invokes his supreme apostolic authority (which he does not possess otherwise than as head of the whole Church) when he infallibly condemns the Baden articles as follows:

With the fullness of the apostolic power, We reprove and condemn the aforementioned articles of the meeting of Baden as containing false, rash, and erroneous assertions; as detracting from the rights of the Holy See, overthrowing the government of the Church and its divine constitution, and subjecting the ecclesiastical ministry to secular domination; and as proceeding from condemned premises. We decree that they should forever be considered condemned.[55]

Similarly, when the pope imposes a profession of faith on any individual or group as a condition for union with the Church, it is clear that he is acting as supreme head of the universal Church; as, for example, in the profession of faith prescribed by Pope Hormisdas for the Acacians (517), by Pope Innocent III for the Waldensians (1208), by Pope Gregory XIII for the Greeks (1575), or by Pope Benedict XIV for the Maronites (1743). For it is only as supreme head of the Church that he has the authority to determine the conditions for union with the Church.

Reply to Objection 1: To the first it must be said that it is true that the pope may be acting only as the local bishop of Rome, or Primate of Italy, or Patriarch of the West in such cases. But he need not always be acting only in these more limited capacities, as is clear from what is said above.

Reply to Objection 2: To the second it must be said that if the pope, acting in his capacity as supreme teacher of the universal Church, imposes a doctrine of faith or morals on any part of the Church directly, then by that very fact he also indirectly imposes the same doctrine on the whole Church.

[1] See Lumen Gentium, §25; cf. Pastor Aeternus, ch. 4.

[2] See Vatican Council I, Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith Dei Filius (1870), ch. 3; cf. Lumen Gentium, §25.

[3] Salaverri, De Ecclesia Christi, n. 647.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See Pastor Aeternus, ch. 4.

[6] See Fenton, “Infallibility in the Encyclicals,” 188–89.

[7] See Dei Filius, ch. 3.

[8] See Pastor Aeternus, ch. 4.

[9] The Gift of Infallibility, 46.

[10] See Dei Filius, ch. 3 and Lumen Gentium, §25.

[11] Pope Pius IX, Apostolic Letter Tuas Libenter (1863).

[12] See Mansi, vol. 51, 322 B; cf. Salaverri, De Ecclesia Christi, n. 552.

[13] See Joseph Kleutgen, Die Theologie der Vorzeit verteidigt, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Münster: Theissing, 1867), 97–115; see also my own exploration of this topic in On the Ordinary and Extraordinary Magisterium from Joseph Kleutgen to the Second Vatican Council, Studia Oecumenica Friburgensia 84 (Münster: Aschendorff, 2017).

[14] See, for example, Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Letter Humani Generis (1950), §20; CDF, Doctrinal Commentary, §10.

[15] See Lumen Gentium, §25.

[16] CDF, Doctrinal Commentary, §9.

[17] Joseph Ratzinger, “The Limits of Church Authority,” L’Osservatore Romano (English edition) (Jun. 29, 1994); cf. “Letter Concerning the CDF Reply Regarding Ordinatio Sacerdotalis,” L’Osservatore Romano (English edition) (Nov. 19, 1995).

[18] Tarcisio Bertone, “Magisterial Documents and Public Dissent,” L’Osservatore Romano (English edition ) (Jan. 29, 1997).

[19] See Pope Pius XII, Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus (1950), §12.

[20] See Louis Billot, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (Prati: Giachetti, 1909), 640.

[21] Ibid., 640–41.

[22] Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical Letter Providentissimus Deus (1893), §20.

[23] The Gift of Infallibility, 74.

[24] Kleutgen, Die Theologie, 100.

[25] See Joseph Fessler, Die wahre und die falsche Unfehlbarkeit der Päpste (Vienna: Sartori, 1871).

[26] See The Gift of Infallibility, 80.

[27] See Cuthbert Butler, The Vatican Council, vol. 2 (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1930), 216.

[28] See, for example, Umberto Betti, “Qualification théologique de la Constitution,” in L’Église de Vatican II, vol. 2, ed. Guilherme Baraúna (Paris: Cerf, 1967), 217; Yves Congar, “En guise de conclusion,” in L’Église de Vatican II, vol. 3 (Paris: Cerf, 1967), 1367; Francis A. Sullivan, Magisterium: Teaching Authority in the Catholic Church (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2002), 121; Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting the Documents of the Magisterium (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2003), 167; Avery Dulles, Magisterium: Teacher and Guardian of the Faith (Naples: Sapientia Press, 2007), 69–70, 76.

[29] CDF, Declaration in Defense of the Catholic Doctrine on the Church Mysterium Ecclesiae (1973), §3.

[30] Code of Canon Law [henceforth: CIC] (1983), 751.

[31] See Pope John Paul II, Motu Proprio Ad Tuendam Fidem (1998), §3, 4.

[32] CDF, Doctrinal Commentary, §6; cf. CIC 750, §2.

[33] Lumen Gentium, §25.

[34] Acta Synodalia III/1, 251.

[35] The Gift of Infallibility, 92.

[36] CIC (1917), 1323, §3.

[37] CIC (1983), 749, §3.

[38] Pope Paul VI, Address During the Last General Meeting of the Second Vatican Council (Dec. 7, 1965).

[39] Pope Paul VI, General Audience (Jan. 12, 1966).

[40] Ibid.

[41] John R. T. Lamont, “The Authority of Canonizations,” Rorate Caeli (Aug. 24, 2018).

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Thomas Aquinas, Quodlibetal Questions IX, q. 8, a. 16.

[46] See Salaverri, De Ecclesia Christi, n. 726.

[47] Cited in Salaverri, De Ecclesia Christi, n. 725. Translation taken from Sacrae Theologiae Summa, trans. Kenneth Baker, vol. 1B (Keep the Faith, 2015), 273.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Lamont, “The Authority of Canonizations.”

[51] The Gift of Infallibility, 92.

[52] The Gift of Infallibility, 77.

[53] Pastor Aeternus, ch. 4.

[54] Billot, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, 642.

[55] Pope Gregory XVI, Encyclical Letter Commissum Divinitus (1835), §16.