Recently a well-known Italian writer (certainly no friend to Catholic Traditionalism), Fulvio Abbate, had this comment about one of our Trad forbears, who was born one hundred years ago today:

It is impossible for me to adhere to the myth of Cristina Campo, whose birth is being honoured right now. I understand her clear voice, but I also recognise in her gaze on the petty things of the world a trait of inhumanity – it may seem strange to you – absence of true piety, which is typical of those who wear the threatening light of the divine to trample on true grace, which is always revolutionary, and not akin to the malcontents found in Catholic traditionalism.[1]

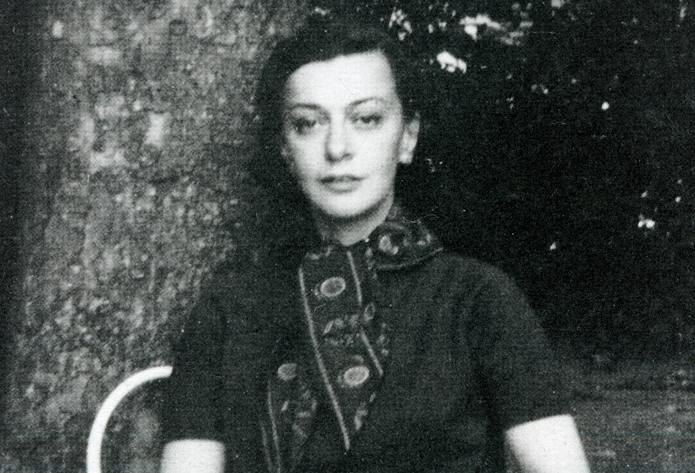

I found this to be rather interesting and becomes an occasion for reflecting on this Trad hero. So who was Cristina Campo?

She was born in Bologna Vittoria Guerrini (1923-1977), but was known by her pen name, Cristina Campo. She was a valuable poet and translator and co-founder of the Italian section of Una Voce. She was behind the Critical exam of the Novus Ordo Missae which caused quite a stir at the time due to its presentation by Cardinal Bacci and Ottaviani.[2]

Yet in addition to her foundational role in Italian traditionalism, Camp was also a tormented soul, both physically and mentally. But who among the faithful was not tormented in those iconoclastic days of the 60s and 70s, when priests destroyed the monuments of our forefathers and literally ripped Rosaries out of the hands of our grandmothers?

Thankfully, Cristina Campo poured her heart not only into important translations, but also poetry, which has been passed down to us. Although translations can never do justice to poetry, I provide here a few English translations of her Italian poetry. In her poem, Missa romana, she asked:

Where does it go

this Lamb

which virgins are given to follow wherever He goes

where goes this Lamb

standing up and killed

in the book of the marked

ab origine

mundi?You can’t be born but

you can stay

innocent.Where does it go

this Lamb

which to us the killers

it is not given to follow with the marked

nor flee

but sobbing sweetly conceive

in the dark womb of the mind

usque ad consummationem

mundi?You can’t be born but

you can die

innocent.

This seems to express the anguish of a pious heart over the violent imposition of the New Mass. Where was this all leading?

Cristina Campo was a controversial figure. She was a close collaborator with Elèmire Zolla, a leading figure of Italian esotericism. At a certain point, like many today, she turned to Russian Orthodoxy to seek what the Catholic Mass no longer gave.

In a book, Don Francesco Ricossa develops a learned and respectful critique: Cristina Campo, o l’ambiguità della tradizione. In it we find a lot of useful information for the evaluation of this extraordinary literate who, experienced first hand the world of symbols and connections that had formed the soul of so many faithful crumbling.

And yet, despite all of Cristina Campo’s contradictions, it would be wrong to give her the negative evaluation found in Fulvio Abbate. Cristina Campo’s tormented heart, as in all of us, is not the “inhuman absence of true mercy,” but that desperation that one feels in the presence of the void that has been created in our religious universe. The monsters Abbate talks about are not those of traditionalism, but those who let their intellects fall asleep and lose the use of reason. Campo’s heart was reacting to what was violently irrational: the clerical, spiritual abuse of modern iconoclasm.

[1] Mi è impossibile aderire al mito di Cristina Campo, di cui si onora in questi giorni il centenario della nascista, ne comprendo la voce tersa, ma ravviso anche nel suo sguardo sulle piccine cose del mondo un tratto di disumana – vi sembrerà strano – assenza di vera pietà, proprio di chi indossi l’abito di luce minacciosa del divino per calpestare la vera grazia, che è sempre rivoluzionaria, e non affine ai mostri del tradizionalismo cattolico.

[2] We recall that for this document, which greatly saddened Paul VI, Father Michel-Louis Guérard de Lauriers also collaborated. Fr. de Lauriers was a distinguished Thomist who would later join the Society of Saint Pius X and subsequently elaborate his theological thesis known by the name of “cassiciacum’s thesis,” giving way to a branch of Catholic traditionalism that takes the name of sedeprivationism