Truth is the first casualty of war—so goes an old saying. We see it verified again in the so-called “liturgy wars,” where, at least on the progressive side, no lie is too big or too bald, if only it can be repeated often enough to convince most people. If one can add a certain sacrilegious touch to it, all the more thrilling!

A case in point, already forgotten in the ceaseless torrent, was Pope Francis’s September 3, 2017 motu proprio Magnum Principium, concerning vernacular translations of the liturgy, and more specifically, the right of episcopal conferences to approve them for their own territories. As is the custom with this pope, most of his documents appear to be named ironically or parodistically. The Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia, which should have been about the joy of that unbreakable charity that the grace of Christ makes us capable of living out, paved the way for dissoluble marriage and normalized Eucharistic sacrilege. The Apostolic Letter Vultum Dei Quaerere put into motion changes that, if not resisted and eventually overturned, will certainly lead to a dropping off of the number of women who are seeking the face of God in the contemplative life—particularly in orders undergoing renewal thanks to the rediscovery of their own deepest traditions. Laudato Si’ starts off with a quotation from St. Francis of Assisi, who, as a mystic of the Holy Eucharist, would have repudiated much of the encyclical’s Teilhardian eco-humanism. Fratelli Tutti, the telephone-book expansion of Abu Dhabi, opens with a blatantly false recasting of the story of St. Francis and the Sultan whom the saint, at the risk of his life, tried to convert to the true Faith. And on and on it goes.

So, too, with this motu proprio, the title of which alludes to the antiphon for the Fourth Sunday of Advent:

Dominus veniet, occurrite illi, dicentes: Magnum principium, et regni ejus non erit finis: Deus, Fortis, Dominator, Princeps pacis, alleluia, alleluia.

The Lord will come, go ye out to meet Him, saying: Great in His dominion, and of His kingdom there shall be no end: He is the Mighty One, God, the Ruler, the Prince of Peace, alleluia, alleluia.

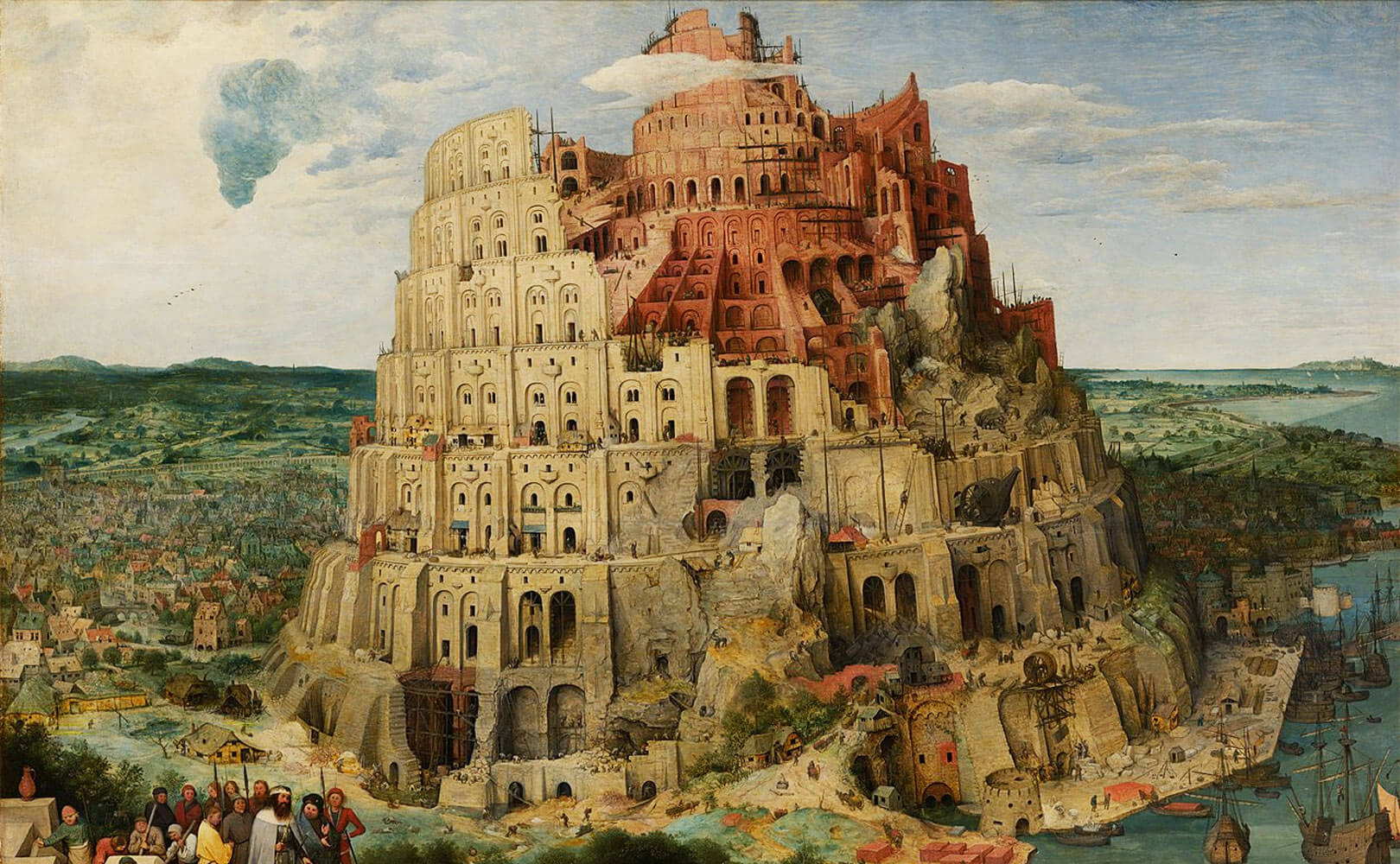

The great dominion of the Redeemer was powerfully witnessed in the Western world by the unity of Roman Catholic worship in a period of over 1,500 years—a unity of which the Latin language was the obvious icon and vehicle. How ironic, then, to take this particular phrase and apply it to the veritable explosion of more or less inadequate (but always tradition-rupturing) translations that followed the building of the Tower of Babel in the 1960s liturgical reform! The very title of the motu proprio carries an ominous ring: the Great Leader has deigned to tell us about the “Great Principle” of the Great Council, for the benefit of the Great People.

Magnum Principium opens with about as breathtaking a series of half-truths as one can find in a papal document of the past 2,000 years:

The great principle, established by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, according to which liturgical prayer be accommodated to the comprehension of the people so that it might be understood, required the weighty task of introducing the vernacular language into the liturgy and of preparing and approving the versions of the liturgical books, a charge that was entrusted to the Bishops. The Latin Church was aware of the attendant sacrifice involved in the partial loss of liturgical Latin, which had been in use throughout the world over the course of centuries. However, it willingly opened the door so that these versions, as part of the rites themselves, might become the voice of the Church celebrating the divine mysteries along with the Latin language. At the same time, especially given the various clearly expressed views of the Council Fathers with regard to the use of the vernacular language in the liturgy, the Church was aware of the difficulties that might present themselves in this regard.

How many half-truths, or, more accurately, lies, are we working with here?

- The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council never placed the verbal comprehension of the people above the principle of fidelity to tradition and the preservation of Latin. In spite of the problems in its reformatory inversion of principles, the document nevertheless went out of its way to state that Latin was to remain the language of the liturgy and that the limits of the vernacular could be extended, especially in missionary regions. The truth is that what happened after the Council well exceeded, or perhaps we might say fell far short of, any natural reading of the texts.

- At the Council, the Fathers (bishops and religious superiors) debated the Latin question at enormous length in the first session, and the “clearly expressed views” in the majority of their speeches were, in point of fact, in favor of preserving liturgical Latin. There were a few speakers who advocated a significant increase in the vernacular, and, if I recall rightly, only a single one, the Melkite patriarch Maximos IV Sayegh, who advocated complete vernacularization—which, surprise!, is what transpired under Paul VI and Bugnini. In no way could one read the debates in the aula and come away with the impression that “the Latin Church was aware of the attendant sacrifice involved in the partial loss of liturgical Latin, which had been in use throughout the world over the course of centuries”—simply because practically no Catholic at the Council dreamed of a world in which liturgical Latin would have disappeared.

- The phrases “partial loss of Latin” and “along with the Latin” are sheer absurdity. I don’t know what planet Pope Francis lives on, but in 99.9% of the Catholic world, not a single word of Latin is heard at any time; there are even bishops who severely persecute those who attempt to use Latin. Perhaps the Pope is thinking too narrowly of the Vatican, which is one of the few places left where Latin is still sometimes encountered in the Novus Ordo.

Magnum Principium was the opening salvo of a liturgical campaign to match the moral campaign of Amoris Laetitia. As the latter document decentralized moral decisions to episcopal conferences, so the former began to do the same for liturgy. Just as one could be in adultery and forbidden from Communion in Poland but go across the border to Germany and be welcomed to Communion as a Christian adult who had self-annulled a marriage by one’s own judgment of conscience, so it will happen that one could attend Mass in a certain country and hear a strictly accurate rendering of pro multis, while in the next country, where the bishops had decided that Jesus should have said pro omnibus, one will hear something different, even in the very sacramental form.

In the 1970s, before his fall from grace, Bugnini was openly saying that the revision of the liturgy was only the first step in a long process of evolution, the final stage of which was a totally “inculturated” liturgy that reflected the needs and demands of each unrepeatable local group (think: Amazonification). In other words, liturgical unity, uniformity, and universality are enemies of authentic individual faith and a worship relevant to modern times. Ratzinger criticized this idea fiercely, but it has always remained the hippie dream of the liturgical progressives, who now have one of their own on the papal throne. He is acting slowly, but with decisive steps—and I’m sure his stacking of the deck of cardinals is designed to ensure a successor as liberal as himself so that the project can be completed.

And I haven’t even gotten into the nitty gritty! Francis says, for example:

The goal of the translation of liturgical texts and of biblical texts for the Liturgy of the Word is to announce the word of salvation to the faithful in obedience to the faith and to express the prayer of the Church to the Lord. For this purpose it is necessary to communicate to a given people using its own language all that the Church intended to communicate to other people through the Latin language.

- It is far from obvious that it is “necessary” to have everything in the people’s language. It is good when the faithful can access the meaning of the liturgical texts, but this can and should happen in many ways, educational, catechetical, homiletic, and with hand missals—and most importantly, it should happen by a long and steady process of assimilation that goes beyond the surface-level of registering familiar words. The worst way to reach the goal of a deep understanding of the mysteries of Christ is to vernacularize the liturgy at a time of unprecedented secularization, theological illiteracy, poetic impotence, and contempt for tradition.

- One cannot communicate all that is contained in the traditional Latin prayers through any modern vernacular. Every translation is a betrayal; all the more so when we are looking at over 1,600 years of liturgical Latin. A hand missal can give the conceptual content fairly well, but the Latin prayer says more, says it better, more subtly and fully and strikingly. Does this make a difference? By all means. The one we are addressing principally is God, and how we speak to Him matters. When we offer Him solemn, beautiful, highly-valued and saint-spoken prayer, it is pleasing in the way that an unblemished lamb is pleasing—in the way that the unblemished Logos offered on the Cross was pleasing. The very fact that countless holy men and women had the very same words on their lips over the centuries endows them with a special efficacy. St. Mectilde of Hackeborn says that the court of heaven rejoices whenever it hears the same words it prayed while on earth.

- As already intimated, there are many other and more important aspects of communication than mere verbal comprehension. The assumption at work in the motu proprio is that of modern rationalism, which is hardly surprising, since it is the operative philosophy of the entire liturgical reform.

- Over time, the Church saw in her traditional Latin far more than a mere instrument of communication. It was a sign and principle of unity, a representation of her timeless empire of truth, which leads us always back to the roots and makes of us one flock everywhere. Many popes and bishops across the ages have taught the same, indicating that we are dealing with the ordinary universal Magisterium. Pope John XXIII’s Apostolic Constitution Veterum Sapientia, another milestone of 1962, was no more abrogated than the classical Missale Romanum was.

The whole motu proprio Magnum Principium could be critiqued like this. It is either a piece of mendacity and double-dealing that reeks of sulphur, or an historic monument to the depths of ignorance and error to which the “spirit of Vatican II” has led its captives. With my forefathers in the Faith, I will gladly stick to the old missal and the old breviary, allowing the phrase to be reabsorbed into its higher and superior origin: Dominus veniet, occurrite illi, dicentes: Magnum principium, et regni ejus non erit finis: Deus, Fortis, Dominator, Princeps pacis, alleluia, alleluia.