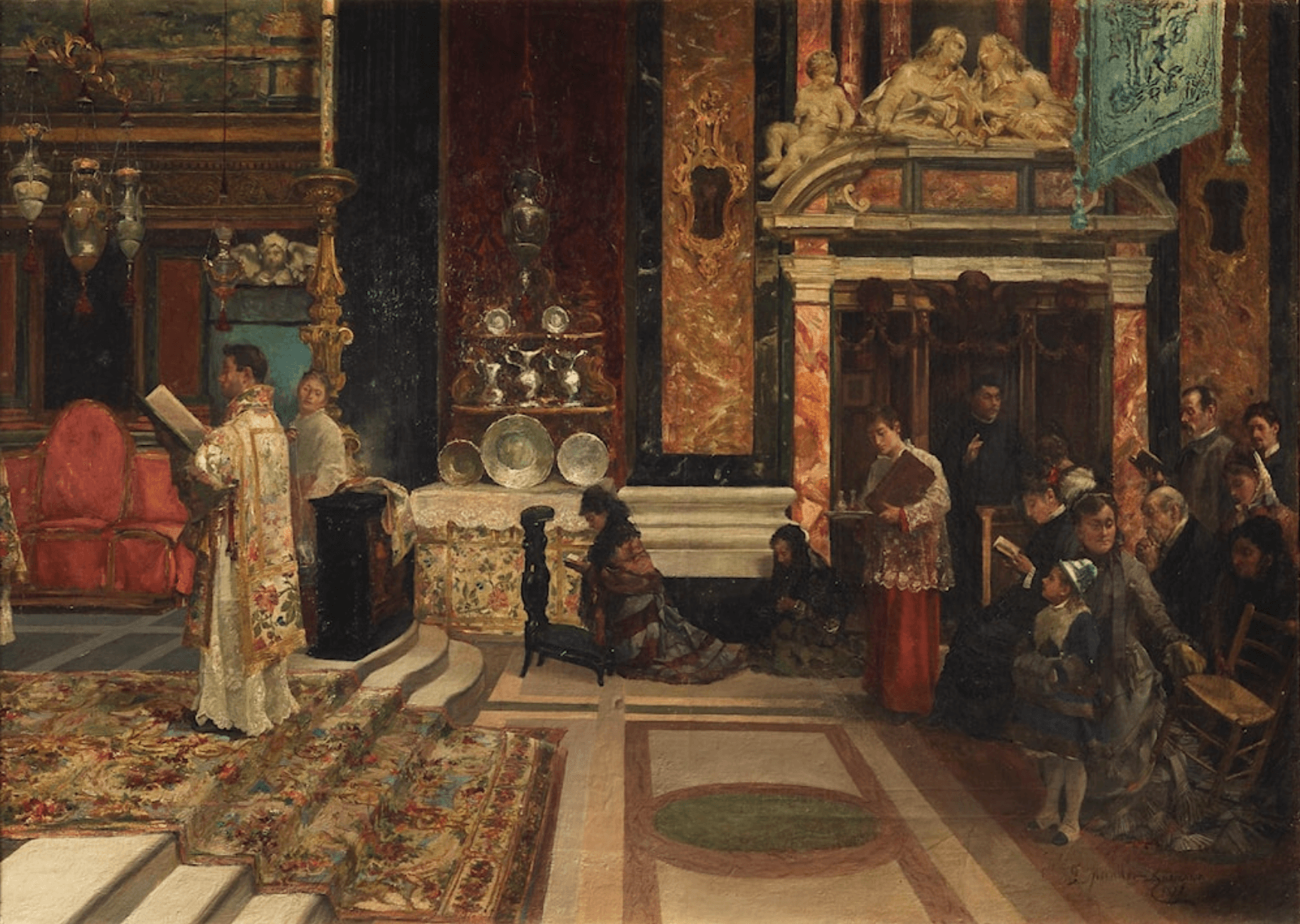

Painting: “A Mass Scene” by José Miralles Darmanin (1851–1900).

Some people object to the phrase “traditional Catholic,” as if it were redundant: Aren’t Catholics by definition adherents of Catholic tradition—and thus, any Roman Catholic has as much right to be called “traditional” as he has to be called “Roman”?

How sweet it would be if this were true. Alas, it is far from being the case.

Let’s take up the charge of redundancy first. “Roman Catholic Christian” may seem like a triple redundancy, yet it is useful precisely because there are Protestant and Eastern Orthodox Christians, as well as true Catholics who are not of the Roman rite. “Traditional Catholic,” likewise, is no redundancy, because there are so many Catholics who are (intentionally or not) Modernists in their thinking and their practices. In an ideal world, the Christian ought to be the Catholic, just as the Catholic ought to be traditional; but even as not every Christian is Catholic, not every Catholic is traditional in a meaningful sense of the word.

Pursuing this point, we would be deceiving ourselves if we did not recognize that it is quite possible today—in a startling and unprecedented way—for Catholics not to be traditional, not to be thinking and living in accordance with major elements of their trimillennial tradition such as asceticism, liturgical rectitude, and adherence to orthodox doctrine. For the first time, we have seen the widespread acceptance of an interpretation of Catholicism that is anti-traditional, that considers itself free from Tradition, free to adopt new and ever-changing shapes according to “modern needs.” (Apropos the concept of aggiornamento, Karl Barth asked the Catholic Church this uncomfortable question in 1966: “When will you know if the Church is sufficiently updated?”)

This is the Achilles’ heel of every conservative critique of traditional Catholicism: as Bugnini & Co. did in the liturgical reform, the conservative has to pick and choose what’s worth keeping and what ought to be discarded, as if he were standing outside of tradition, history, and magisterium, standing over it rather than submitting to be formed, measured, and judged—by all of it, not simply by the latest issue of L’Osservatore Romano.

The New Tyranny of Progress

Cardinal Siri made these pointed remarks in the January 1975 issue of the Rivista Diocesana Genovese:

Slogans abound, while catechism is not taught; “pastoral” is continually mentioned, while sacred ministries are gradually abandoned; there is talk of the Word of God—yet it is taught as if it were all a fairy tale. There are dissertations about closeness with God, while at the same time the Most Blessed Eucharist is mocked or ridiculed. At least in practice. And all of this is progress!

One might have thought, in recent years, that Catholics were at last beginning to escape the shadowlands of the seventies, leaving its pomps and works far behind. Alas, in the Church today we are seeing a renewed effort on the part of some to promote the same old postconciliar “progress” lamented by Cardinal Siri. We are being given as our “pastoral model” a modus operandi that originated in the secularizing confusion of the years immediately following the Council—a modus operandi that badly failed back then and will, by God’s justice, fail again and again, since it is anti-traditional in content, method, and goals.

Indeed, something worse has come upon us: a return to the open denigration, marginalization, and persecution of traditionalists. Coming on the heels of the Emancipation Proclamation (Summorum Pontificum) has been a new regime—a Pharaoh who knew not Joseph Ratzinger, so to speak—intent on reintroducing slavery or, at best, arranging strict segregation and second-class citizenship. In the realistic words of Don Ariel di Gualdo:

We did have the Second Vatican Council, but, in practice, during the following years, we returned to the period that preceded the Council of Trent, with its corruption and alarming internal struggles for power. After abundant discourses ad nauseam about dialogue, collegiality—for nearly half a century now [this was written in 2013]—new forms of clericalism and authoritarianism have emerged. The progressive champions of dialogue and collegiality use aggression and coercion against anyone who thinks outside of the “religiously correct.”

In normal circumstances, “Catholic” should be equivalent with “traditional.” Today, it decisively does not mean that. With the infiltration of Modernism into the highest echelons of the Church, it cannot mean that, for some individuals. Yet, since part of the definition of being a Catholic is—and must always be—to adhere to the Tradition handed down to us from the saints and to honor and preserve ecclesiastical traditions in globo, it follows that an explicit or implicit adherence to Tradition is necessary for salvation, whereas hating or despising Tradition is a sign of one’s intention to depart from the Church of Christ, placing one’s soul in jeopardy as a result.

There is far more resting on this matter than a particular person’s preference or inclinations: the salvation of souls is at stake. The evangelii gaudium or “joy of the Gospel” is bound up with knowing the truth, confessing it in season and out of season, and clinging to it with the determination of love. May God preserve us from the false joys of this world and all of the new Gospels that clamor for acceptance!

An Objection from Benedict XV

Sometimes our critics reason in the following way: Tradition is obviously a major component of Catholic life, and the handing on and receiving that Tradition a major task of the Church; but it’s only one of a number of such components. Tradition (continues this objector) is not so much a criterion of truth as it is a means of knowing truth and, to some extent, a guarantee of truths. Even if the necessity and value of Tradition is denied today, that doesn’t seem to be a sufficient reason to choose the term to identify ourselves. We shouldn’t over emphasize a truth that someone else denies; rather, we should give it its proper place in our thinking. Aren’t you familiar, after all, with Pope Benedict XV’s criticism of putting a qualifier in front of Catholic? He wrote in his 1914 encyclical Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum:

It is Our will that Catholics should abstain from certain appellations which have recently been brought into use to distinguish one group of Catholics from another. They are to be avoided not only as “profane novelties of words,” out of harmony with both truth and justice, but also because they give rise to great trouble and confusion among Catholics. Such is the nature of Catholicism that it does not admit of more or less, but must be held as a whole or as a whole rejected: “This is the Catholic faith, which unless a man believe faithfully and firmly; he cannot be saved” (Athanasian Creed). There is no need of adding any qualifying terms to the profession of Catholicism: it is quite enough for each one to proclaim “Christian is my name and Catholic my surname,” only let him endeavor to be in reality what he calls himself.

What might be said to such a line of argument?

Benedict XV is surely right that confusing or impertinent qualifiers should be avoided—subjective categorizations such as progressive, modern, contemporary, liberal, or conservative, which tend to mix up secular politics, sociology, and religion. For example, one cannot actually be a “liberal Catholic,” since this is a contradiction in terms. “Contemporary Catholic” is either tautological (since everyone now alive is ipso facto contemporary) or rebellious (defining oneself against the Catholicism of the past, which would simply amount to excluding oneself from the great communion of the Church of all ages). Nor does the term “conservative Catholic” have much of a meaning, because it leaves entirely vague what is being conserved and why. (In any case, conservatism is nothing but liberalism in slow motion.) There might be a whole host of such qualifiers that either involve conceptual contradiction or convey nothing substantive and relevant.

Wearing the Badge with Honor and Truth

There is, however, a quite definite and defensible way in which one may call oneself a traditional Catholic or even a traditionalist, and wear this name as a badge of honor.

Contrary to the trend of the objector’s argument, the Catholic Faith is not just bound up with Tradition, it actually exists in the mode of tradition—that is, in the mode of something handed down; and this is the only way in which it lives and moves and has its being. Just as Almighty God saved us not by means of an abstract metaphysical system but through a messy and lengthy history, so too, he established the Catholic Church and its doctrine and life as a reality entrusted to the apostles and transmitted, by them, to succeeding generations. While one can have a catechism that reads as if it fell from the heavens with an objective and timeless content (a style highly appropriate for a catechism, no doubt), the faith is a living reality put into certain chosen peoples’ hands and handed over by them to us who now believe. In a broad sense, the entirety of revelation—including Scripture—is part of Tradition. Scripture, too, has been delivered to the Church and handed down by her to us.

This transmission is integral, complete, undistorted, and essentially unchanging, as Saint Vincent of Lérins sees it. St. John Henry Newman shows with rigorous reasoning how the legitimate developments that have occurred historically affected not the body of the truth but, as it were, its clothing, or, to put it differently, not the truth of the word but the fullness of its verbal expression. While the crisis of Modernism can be understood in many ways, the crux of the matter is an adoption of an Hegelian (although one might just as easily say Darwinian or Marxist) understanding of development of doctrine: what we believe now, how we practice and pray, are and ought to be different from what they used to be, simply because our age is different—our experiences, feelings, mentality, science, are different. The traditional Catholic decisively rejects this Hegelian deception and affirms the Vincentian/Newmanian unity of revelation as handed down over time, with the guidance of the Holy Spirit leading the Church into the fullness of truth.

Once one grants that there is an integral truth handed down over the centuries and developed organically, then it must be possible for deviation and corruption to set in because of the sins of Christians. Heresy is always possible; misunderstanding, distortion, overemphasis, underemphasis, secularization, all of these things can happen; and when they happen, they begin to undermine “the faith once delivered to the saints” in the souls of individuals who are not strong in the knowledge and practice of the faith—including members of the Church hierarchy.

This was seen most famously in England at the time of the Reformation, when all the bishops except St. John Fisher went along with King Henry VIII’s machinations. We see it today in the clear split between the bishops who accept and teach authentic Catholic doctrine on marriage and family and those who do not, or between bishops who know and clearly state that the Catholic Church is the one true Church of Christ to which all Protestants are called by God to return, and those who counsel people to remain in their objectively erroneous positions either temporarily or permanently.

A Point of Distinction

At precisely this juncture arises a point that does, I would say, distinguish traditionalists from other Catholics. A traditionalist believes it to be possible—and to have really happened—that a pope or a council could introduce language or liturgy that departs from the constancy, integrity, and purity of the Catholic tradition in its “received and approved” form, not in such a way that dogma is contradicted outright or sin commanded, but in such a way that doctrines are thrown into confusion, errors are invited, deviations are disseminated. If such a thing has taken place, the solution is not to throw overboard that which is ancient, venerable, and constant, but to judge as inadequate and dangerous that which departs from it, and to hold fast to the tried and true.

Let us return to Pope Benedict XV’s point. The qualifier “traditional” attached to “Catholic” is as coherent and meaningful as the familiar qualifier “Roman”—nay, far more so, since “Roman” might be interpreted by the less educated as a claim that all Catholics belong to the Latin Rite, which is quite untrue, whereas “traditional” emphasizes that our faith comes to us in the singular mode of a depositum fidei communicated by Christ the Lord to His apostles, and by them to their successors, with the essential content of faith and morals never changing, and their immediate echoes, such as liturgy, monasticism, and Catholic social doctrine, being carefully preserved, guarded, enriched, and passed on.

In short, if things were not so rotten in the proverbial state of Denmark, “traditional Catholic” would be a redundancy, as there would be no other kind to speak of; but in a world where one finds non-traditional and anti-traditional people counting themselves as Catholics, a clarifying moniker separates the (formal or material) Modernist from the anti-Modernist. In an age of increasing darkness, such clarity is much needed and much appreciated by those who are seeking fundamental, not superficial, solutions.

But Isn’t it Pharisaical to Call Oneself “Traditional”?

It is sometimes asserted that traditional Catholicism is bound up with a prideful attitude—that it is impossible to profess traditionalism without being pharisaical.

Such a claim is too simplistic and too narrow. There is a danger of pride or pharisaism in any true description of oneself: Christian, Catholic, Roman Catholic, traditionalist. To say “I am a Christian” is a genuine boast for St. Paul and for every martyr who has died for Jesus Christ, including the God-fearing victims of Islamic extremism. Are we to say that because there might be someone who revels too much in the title of Christian and thinks himself better than his unbelieving neighbor, the very title ought to be abolished? One might just as well avoid baptism, which, thanks to no merits of our own, truly makes us better than we were before, and far better off than any unbeliever.

There are dangers of pride in any state or way of life. As the wokus-pokus pseudo-religion has proved, there’s no less a danger of being proud of one’s supposed “open-mindedness” or freedom from ideology, one’s immunity to “judgmentalism,” one’s superbly balanced apprehension of the power-grabs that underlie all institutional realities. One can be, paradoxically, a Pharisee of open-mindedness, an ideologue of dialogue, a dogmatist about refusing to dogmatize. One can be simplistic by seeing everyone who takes a strong line as a simpleton.

The only one who can escape pride, judgmentalism, and ideology is the one who completely submits his mind to an objective external standard, one who submits his heart to another whom he loves without qualification. The traditional Catholic is one who says: There is such a standard, and it is Divine Revelation, communicated to us in Scripture and Tradition and guarded by the perennial Magisterium. There is such a beloved, our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom absolutely everything—all human actions and sufferings, all arts and sciences, all cultures and governments, cities and nations—must be intentionally ordered if they are to achieve their God-given purpose. And when they are not so ordered, they are doomed, over time, to feebleness, perversion, anarchy, and suicide. The traditionalist can maintain these positions humbly because they are true. It is, after all, the truth that sets us free.

The traditionalist desires to receive humbly what the Lord has given. He desires to open wide his heart to a blessed inheritance that is always so much greater than his own limited mind can comprehend, much less improve upon. The pridefulness of the modern(ist) Catholic consists in thinking himself superior to his Catholic inheritance—in a position, one might say, of “self-absorbed promethean neopelagian” creativity towards what has been devotedly handed down, century upon century. The judgmentalism of the modern Catholic can be seen in his dismissive attitude towards traditions and the traditionalist who loves them, whom he refuses to see as a lover of the full breadth and depth of Christ and of His Church, and whom he finds it easy to caricature as narrow-minded, rigid, joyless Pelagian, et cetera.

We rejoice, then, to call ourselves traditional Catholics (or traditionalists), which does not distract from, but rather articulates and resolutely defends the glory of our Christian name and Catholic surname. And it is no less true that the exhortation of Benedict XV can also be addressed to each of us: “Only let him endeavor to be in reality what he calls himself.”