Recently I’ve been reading The Hobbit to two of my young children. Central to the story is lost treasure: Thorin and his fellow dwarves ask for Bilbo Baggins’ help in reclaiming their trove, which has been captured by the dragon Smaug and hidden deep within the Lonely Mountain. As I read the book, I can’t help but think of our own day’s lost treasure: the liturgical patrimony of the Catholic Church.

After the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), massive changes were made to the liturgy which involved the abandonment of many traditional practices. None were more noticeable to the average Catholic (and even non-Catholic) than the abandonment of Latin in favor of the vernacular. Yet there have been many other changes, and although they are not as noticeable to the casual observer as the loss of Latin, they are each sadly significant nonetheless.

Now, one might imagine that someone lamenting these losses is simply a nostalgic child of the 50’s, pining for the Church of his youth. However, I was born after Vatican II ended, and didn’t even become Catholic until the 1990’s. I never even attended the “old Mass” until about 10 years ago. Further, I came into the Church by way of the charismatic renewal, which isn’t exactly known for old-school liturgies. And if I’m being completely honest, I generally prefer a liturgy in English. Yet over the years the treasure we’ve lost has become more evident, and more painful, to me.

9 Liturgical Losses

Here are some of those lost aspects of the Roman liturgy from the past 50 years, in no particular order:

1) Ad Orientem

We no longer celebrate the Mass with the priest leading us to the Father. Instead, we gaze at each other while proclaiming How Great We Art. I can’t imagine a more dramatic symbolic divergence than turning the priest away from God and towards the people he’s supposed to be leading. It’s like Moses trying to lead the Chosen People to the Promised Land without ever actually looking toward Zion.

2) Altar Rails

The altar rail was a staple of Catholic churches for generations. Then it was tossed aside like a Hollywood actor discovered to be a conservative. This loss has led to secondary losses: the practice of receiving communion while kneeling, and the distinct separation between the sanctuary and the nave. (In fact, most people don’t know what a nave is, and call the whole church a sanctuary).

3) Communion on the Tongue

Although Communion on the tongue is still allowed, the vast majority of people receive communion in the hand now. I once attended a First Communion retreat for one of my daughters in which the presenter told the children that First Communion meant they had grown up, and only babies are fed in the mouth. Afterwards, I told my daughter that in the eyes of God, we are small children, and receiving on the tongue signifies our complete dependence on the Lord, like little birds receiving food from their mother.

4) Bowing of the Head at the Name of the Three Divine Persons, or Jesus, or Mary

The first time I ever attended a Latin Mass it was an elaborate High Mass with dozens of seminarians and priests serving. At every mention of the name of Jesus or Mary or the Three Divine Persons, every single one of them bowed their head in unison. I was struck by this gesture of respect, and thought to myself, “Now these people have respect for the Faith.”

5) Sacred Music

To compare today’s Haugen-Haas mess with the beautiful musical patrimony of the Church is to compare a package of Starbursts with a seven-course meal at a five-star restaurant. Today’s music is sickly-sweet and leaves you empty, while music that stirs the soul and lifts the heart heavenward has been forgotten.

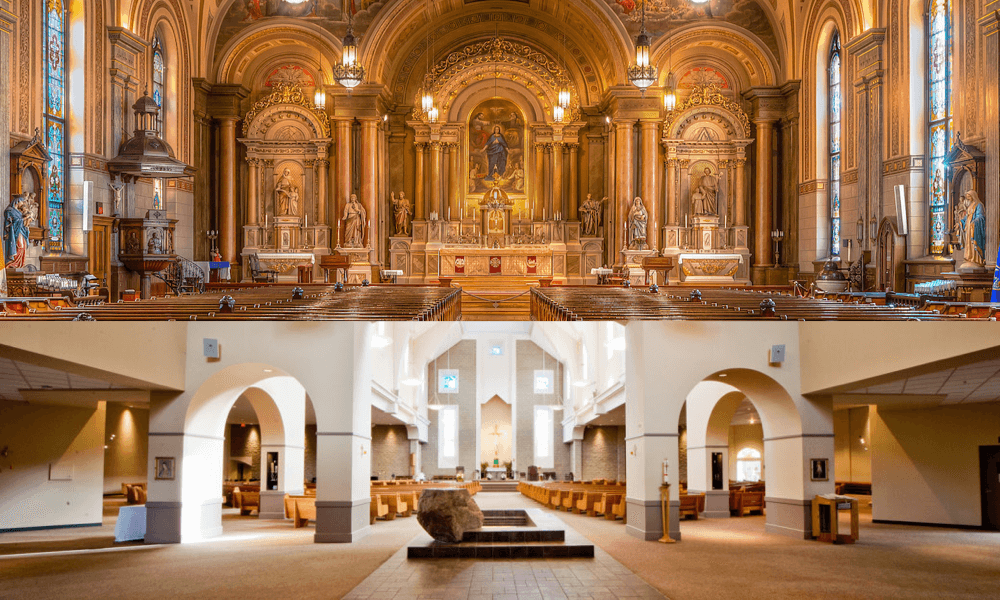

6) Sacred Architecture

For centuries, communities would band together to build, at great expense and sacrifice, churches worthy of the Almighty God. But if you tour the well-off suburbs of America, you see Pizza Hut parishes and what appear to be abandoned airplane hangers posing as Catholic churches. The feast for the eyes that are older Catholic churches has been replaced with the battle of the bland and blander. No longer do you walk into a Catholic church and immediately know you’re in a sacred place where the Lord is worshipped. If you didn’t know beforehand, you might think its where you go to get your driver’s license renewed.

7) Use of the Paten When Receiving Communion

Once communion in the hand became commonplace, the simple paten, which the altar boy placed under your chin lest any of the precious Host fall onto the ground, was retired. Yet the paten represented something: that we really, truly believed that what we were receiving wasn’t a piece of bread that could be trampled upon, but instead was the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ.

8) Altar Boys

In our culture’s quest to become genderless, the Church has felt the need to placate that culture as much as possible. Thus gender-specific roles, if they were not divinely ordained like the priesthood, were abolished. The training ground for future priests became something we wanted little Sarah to do, because “she’d be just as good at it as Johnny.” Of course, it was never about ability, but instead reflected the imaging of the God-man Jesus Christ and the essential differences in roles between men and women.

9) Genuflecting at the Final Blessing and During the Creed

Protestants like to joke that there is a lot of standing and kneeling at a Catholic Mass. And compared to a typical Protestant service, they are correct. Yet even that had to be streamlined in our efforts to “simplify” the liturgy. So ancient practices of genuflecting for blessings, or while proclaiming the Incarnation during the Creed, have been shunted aside. Gone is another gesture of reverence to remind us of the great mysteries we are celebrating.

Exponential Losses

Each loss, by itself, might seem a minor thing. None of these lost aspects, of course, impact the validity of a Mass. The Eucharist is still the Eucharist in today’s Mass. But each loss – especially when combined with all the other ones – substantially impact our reverence when celebrating the sacred mysteries. They impact our subjective reception and participation in the graces we receive at the Mass.

Also, note that none of these things are related to Latin in the Mass. After all, almost every one of these aspects of the Liturgy we’ve lost are retained in the Eastern liturgy, which is usually celebrated in the vernacular, and never in Latin.

The reasons that were given for the discarding of traditional liturgical practices was that it would allow people to participate more fully, and would make the Mass more palatable to the “common man.” The evidence, however, points in the opposite direction. “Simplifying” the liturgy has made it less special, which has made it less attractive to attend. On a Sunday morning, when someone has a choice between relaxing at home or attending an insipid imitation of a bad high school musical, what will the common person choose? However, if the option were a reverent partaking of heavenly mysteries that transports one beyond space and time, it might be a far more compelling choice than checking out the Sunday news shows.

I tend to look at most things in the Church through an evangelization lens since I’ve been involved in Catholic evangelization for decades. I’ve written before that the purpose of the Mass is not evangelization but the glorification of God. Yet there are evangelization consequences to poor liturgies (and I mean poor in two senses of the word: badly executed and with a poverty of reverence). It sends a signal that we don’t take this God stuff too seriously, and you shouldn’t either. Is this the message we want to send to the world?

Catholics should mourn for what has been lost in the liturgy in the past generation. These losses have contributed to the Church losing much of her soul, and in the process, losing many of her members as well. Let us pray for Bilbos to arise and work tirelessly to restore the lost treasure that has been buried out of sight for so long. To do so might involve fighting dragons, but the treasure we are working to unearth is worth it.

Ad orientem. Please fix the typo.

That one is on me. Thanks. Fixed it.

How about the 1 year reading cycle? Immutable Canon? _Actual_ Rubrics (not merely suggestions)? Proper Offertory prayers? Proper Liturgical Seasons (no “Ordinary Time”) in line with history? Non-demolished Sanctoral Cycle? The Confiteor? Holy Days of Obligation on the actual day? First and Second Vespers? Processions? The Roman Ritual? Ember Days? Rogation Days? Septuagesima Season?

You can fix what people see all you want, but unless you fix their belief, it is all naught. Lex orandi, lex credendi. The problem goes much deeper than Altar boys, Communion in the Paw, and the Paten.

Fix all of these things. Yes, it is a much deeper problem. A few churches have kept the altar rail, communion on the tongue, boys only as altar servers, use of the paten, sacred architecture and sacred music. No lay EMHC. The comparison of just these few simple items to the churches that have gone full scale modern is the difference between night and day. I call these more traditional churches “real Catholic Churches” in comparison to “the Protestant version of Catholic Churches”. Prayer, belief/ doctrine and practice — all these things matter greatly.

Excellent

So true.

The 9 things are a good start, but we have lost so, so much more.

There are not enough upvotes in all the world for this.

The Sixth Commandment?

LOL!! (oh dear)

I would also add Candlemas to this list. Having grown up in a diocesan parish, I can say I had never even heard of Candlemas until I discovered the TLM in college.

Pentecost Octave

Confiteor remains, Holy Days of Obligation remain. Some Processions (Marian, Palm Sunday and CorpusChristi). The last four I don’t know at all.

Not *the* Confiteor. Not the same as recited by St. Therese the Little Flower, or St. Francis of Assisi, or St. Thomas Aquinas. Some Holy Days of Obligation remain — the Ascension is typically moved to the following Sunday, as is the Assumption. Modern parishes do not typically do an outdoor, public procession. My first Corpus Christi procession was at an FSSP parish when I was 32.

There is a LOT to restore.

Are you a convert James? Could you share that version of the Confiteor. Thanks.

I am not a convert, but the Confiteor from the TLM is:

Confiteor Deo omnipotenti, beatae Mariae semper Virgini, beato Michaeli Archangelo, beato Joanni Baptistae, sanctis Apostolis Petro et Paulo, omnibus Sanctis, et vobis, fratres (et tibi pater), quia peccavi nimis cogitatione, verbo et opere: mea culpa, [strike breast] mea culpa, [strike breast] mea maxima culpa [strike breast]. Ideo precor beatam Mariam semper Virginem, beatum Michaelem Archangelum, beatum Joannem Baptistam, sanctos Apostolos Petrum et Paulum, omnes Sanctos, [et vos, fratres (et te, pater)] orare pro me ad Dominum Deum nostrum. Amen.

I confess to almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the archangel, to blessed John the Baptist, to the holy apostles Peter and Paul, to all the saints, and to you my brothers (and to thee, father) that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed, through my fault, [strike breast] through my fault, [strike breast] through my most grievous fault [strike breast]. Therefore, I beseech blessed Mary ever Virgin, blessed Michael the archangel, blessed John the Baptist, the holy apostles Peter and Paul, all the saints, [and you my brothers (and thee father)] to pray for me to the Lord our God. Amen.

While the version from the new missal is:

I confess to almighty God

and to you, my brothers and sisters,

that I have greatly sinned

in my thoughts and in my words,

in what I have done

and in what I have failed to do,

through my fault,

through my fault,

through my most grievous fault;

therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin,

all the Angels and Saints,

and you, my brothers and sisters,

to pray for me to the Lord our God.

Really…wow. Will copy that. Seems so odd to confess to an archangel.

I am confessing that I have sinned to those from whom I will later ask for intercession to almighty God. It was the Confiteor for a millennium prior to the changes introduced after the Second Vatican Council.

I see that. I plan to introduce in my prayer. We have no TLM in my country. No living priest who will offer.

Where are you? Do a 54-day novena to Mary. She will provide this most worthy request, IMHO.

I’m planning to start the 54-Day Novena to the Holy Face tomorrow.

I’m in Jamaica, W.I. With our whopping 2.5% Catholic population and dwindling.

A 54-day novena? Novena means nine days. I’m intrigued.

Lol.. true. I guess you do the Novena 6 times over a period of 54 days…54 Rosaries.

Another explanation of the 54-day Rosary Novena:

[Please note that this is the traditional rosary, said without the Luminous Mysteries.]

++Three nine-day Novenas for a specific petition (Days 1 – 27)

After the first “Our Father, three “Hail Mary’s,” and “Glory Be” and “O My Jesus,” each day, petition the Blessed Virgin Mary to intercede on your behalf that your prayer of petition will be answered:

Novena One (9 days) —

Days 1, 10, and 19 – Five Joyful Mysteries

Days 2, 11, and 20 – Five Sorrowful Mysteries

Days 3, 12, and 21 – Five Glorious Mysteries

Days 4, 13, and 22 – Five Joyful Mysteries

Days 5, 14, and 23 – Five Sorrowful Mysteries

Days 6, 15, and 24 – Five Glorious Mysteries

Days 7, 16, and 25 – Five Joyful Mysteries

Days 8, 17, and 26 – Five Sorrowful Mysteries

Days 9, 18, and 27 – Five Glorious Mysteries

++Three nine-day Novenas of Thanksgiving (Days 28-54)

After the first “Our Father, three “Hail Mary’s,” and “Glory Be” and “O My Jesus,” express gratitude to the Blessed Virgin Mary and to God that your petition has been answered. (You answer may be obvious, or not, but it is *always* answered.)

Days 28, 37, and 46 – Five Joyful Mysteries

Days 29, 38, and 47 – Five Sorrowful Mysteries

Days 30, 39, and 48 – Five Glorious Mysteries

Days 31, 40, and 49 – Five Joyful Mysteries

Days 32, 41, and 50 – Five Sorrowful Mysteries

Days 33, 42, and 51 – Five Glorious Mysteries

Days 34, 43, and 52 – Five Joyful Mysteries

Days 35, 44, and 53 – Five Sorrowful Mysteries

Days 36, 45, and 54 – Five Glorious Mysteries

How far is Martinique from you? Probably a long way 🙁 The SSPX have a Priory there.

At least you have Sabina Park not far from you.

How does one do a 54 day novena to the Blessed Mother for the intention of having TLM in our area? Is it just 54 rosaries? Are there other specific prayers that should be said? I live in Souteastern North Carolina. I have been a Catholic for 47 years. Converted in 1970, just after VII. I can just barely remember altar rails and Communion on the tongue. I have never been to a Latin Mass, just an NO done inLatin once at a Newman Center I attended. The Monsignor did it as a special favor to some who asked for a “Latin” Mass. Monsignor thought few people would come, but the large church was packed! He had two nights of classes before the Mass for those who wanted to attend to teach us how to say the responses in reasonably correct Latin. Those classes were packed, too. Even the NO in Latin was beautiful! We all wanted more, but it never happened. Sad.

The 54 day novena goes like this:

1st Day – Joyful Mysteries in petition for favor

2nd Day – Sorrowful Mysteries in petition for a favor

3rd Day – Glorious Mysteries in petition for favor

4th Day – Joyful Mysteries in petition for favor

The sequence is repeated days 5 – 27 in petition; days 28 – 54 are made in thanksgiving for a petition, even if it has not been granted yet.

Thank you so much for explaining this to me! God bless you!

You’re welcome. Btw, if you noticed, only the Joyful, Sorrowful and Glorious Mysteries are used NOT the Luminous mysteries.

I highly recommend The New Rosary by Christopher A. Ferrara. It’s a little booklet, very easy to read and explains why one should NOT use the Luminous mysteries.

77reid, I attend a Latin Most Holy Mass at my Catholic Parish Church here in the U.S.A. , in Latrobe, Pennsylvania . I PROMISE YOU, my DEAR SPIRITUAL SISTER that I will carry you with me in PRAYER there at every Most Holy Latin Mass that I attend there. The name of the Catholic Parish Church is called — Holy Family Church. You are in my Heart and in my Prayers. THANK YOU. From— Michael Long. E–mail is —- [email protected] PLEASE KEEP me in Your Prayers as well.

Where’s Latrobe?

To Margaret, Latrobe, Is in Westmoreland County, in Pennsylvania , It is between Greensburg and Ligioner. Where are you from ? My E-mail is — [email protected] From—– Michael Long

Where are you, 77?

V2 and the novus ordo sacraments are a new religion.

Well, it has been revised since (sommorum pontificum); So the striking of the breast and mea culpas are back.

The Communion of the Saints is still suppressed in the novus “confiteor”. It is optional at the mutilated version of the “Communicantes” in the Canon, and at the redacted version of the “Libera nos” after the Our Father.

http://www.liturgies.net/Liturgies/Catholic/TridentineLatinEnglish.htm

Right.

The supression of the Communion of the Saints. It occurrs at other places in the novus as well.

St. Thomas Aquinas was a Dominican. He celebrated the Dominican Rite which was different from the Roman Rite. There was no triple “mea culpa”. St. Dominick’s name was mentioned in the Confiteor instead of the other saints.

That illustrates my point. St. Dominic would not recognize the current version of the Confiteor.

James, YES a lot to Restore. So many things the Saints Held as Most Precious are now gone. From — Michael Long. E–mail —- [email protected]

The fact you don’t know the last four is very telling of what has been stolen from all of us. I wasn’t aware of what any of those were until just before Lent this year. We’ve been robbed and we must do what we can to reclaim what belongs to us!

How will we restore this unless priests are willing and it is approved?

“We” won’t. Only He will. We won’t like it, though. The restorative process is never fun, easy, or without pain. It is easier to lose, than it is to gain, and it is much harder to regain than it is to obtain it the first time around.

The Church must suffer, carrying her cross.

http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p1s2c2a7.htm

Amen. Thank you. And His Bride has come down from heaven. Many times.

Priests of traditional orders and societies such as the FSSP and ICKSP often still observe these days and practices. They’re all part of the Traditional Roman Calendar that is still used to celebrate the TLM. We can begin to honor these days too at least as regards fasting and abstinence if the TLM is out of our reach.

True. I will look it up.

“Priests of traditional orders and societies such as the FSSP and ICKSP often still observe these days and practices.”

*always* observe.

Thanks for the correction 🙂

Until I stopped going to the Novus Ordo, I assisted at Novus Ordos in about four different countries and not once was there a Confiteor.

Brilliant article. Could not agree more. Might add “meaningful and or educational homilies”. I am weeping right next to you Mr Sammons. Tears!!

To all out there….. use your God-given talents and keep fighting!

Whether you are teaching, singing, serving, etc, etc…. we all need to do our part and get in the game. We can turn this Ship around. God knows we can 🙂

“Meaningful or educational homilies” ….. what, pray tell, might those be? I learn more about my Catholic faith from YouTube videos, Catholic publishing companies, St Paul Bible Institute, Formed, Ascension Press, Lighthouse Media, Catholic Radio, classic spiritual readings, etc. than I have ever learned at mass. Seriously, the homily is a matter of endurance (most of the time I just grit my teeth through it) and I would be just as happy if it were done away with altogether. Don’t get me started on that particular topic …..

Yes, thankfully there are so many resources we can use to educate ourselves these days. From my own experience, most people who want to become Catholic do so in spite of the RCIA program rather than because of it.

Exactly!! I literally come home from Mass and listen to the Sunday homily at Reginum Prophetarum. You might enjoy those as well. God bless!

How about Churchmilitant.com?

Voris is a poisonous individual.

Why do you say that, specifically?

He caved into the wishes of his organisation’s main donor and commenced about two years ago a sustained and virulent attack on the SSPX, calling them schismatics (and heretics I think too), thereby reversing himself for filthy money.

Now of course he looks like a complete moron, given that the SSPX is already allowed to ordain priests without the local Ordinary’s permission, hear Confessions and conduct marriages.

His site then conducted a terror campaign against subscribers and others who complained or simply sought to leave online comments disagreeing with him.

And this is before one considers his earlier life, which though happily ended, does throw up questions about his integrity.

Along with many others, I won’t even look at his site now.

His organization’s main donor? Who’s that? Or who was that?

Some bloke in Texas I read. Not interested.

Thank you! I was tempted to stop giving the adult catechism lesson in my parish until I read your post.

You are a God-send!!! XO

Oh awesome!!! I am a catechist as well, for youth, and this year has been so very difficult that I too have been near despair. However, even if they hear the Truth from no one else, at least they have heard it from me. So, please, keep planting those seeds of Faith. We all have to give an account of how we helped to build the Kingdom and your efforts will not be in vain. God bless you!!!

I would jump for the opportunity to be in your class Margaret,and so would my husband!

Keep on!

With God’s help and direction!

I would love to have altar rails back. I receive Our Lord on the tongue.

Me too. And we still have patens at our NO parish, but, although Mass is not offered ad orientum (sp?), I think it’s because we have a newer main church. The pastors have tried to reign in the architectural stuff that HQ, as it were, wanted, I think. So, the Tabernacle is off to the side, but is still greatly reverenced, with candles, praying before The Blessed Sacrament, genuflecting and bowing, etc. Our pastor does his best with what he inherited. And he’s leaving, soon, after 18 years for a larger parish. Maybe we can get a TLM in our historic Chapel. Have to work on that.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hk9dGPO60MU&w=560&h=315%5D

“Gentlemen, welcome to the desert of the Real.”

DISCO-DECAYED

Disco-decayed

They cancelled all color

Sanctuaries stripped

First Communions were duller.

No crinoline whites

Pale hues they stressed

Only pearled-Pharisees

Are ever so dressed.

Roses, carnations,

Flowers, all manners

Left just to wither

Gainst assertive beige banners.

Pillars of marble

Corinthian styles

They decided to paint

Like pink bathroom tiles.

Cassocks of red

Habits blue, white,

Robes of distinction

Extinct over night.

Missals with pages

Embossed in gloss-gold

Latin in tint

English-black to behold.

Even the ribbons

To mark scriptural prayers

Were of green, yellow, silvers

So to keep us from errors.

The soft votive flames

The red opaque glass

Gave an aura of stillness

Like time could not pass.

Yet time it passed

Vividness drained

And populations without color

Cannot be sustained.

So those underground

Tradition’s red in blue veins

Birthe vocations, the True Mass

Great virtues they’ve gained.

They did not decay

God’s colors kept green

For the day up above

Once again to be seen.

Except for those beige

Banner-like-blind

Gray fertility fades

In their black open minds.

Excellent article! Believe me, as an ex-Protestant who was searching for the real faith, #1 is ALL important. Why? Because when I witnessed my first Mass on EWTN (it was 1999 and still Ad Orientem) I recognized that the Catholic Church WAS the Jewish faith that had accepted Jesus Christ as the promised Messiah. Had the priest been facing the people I would never have made the connection. And that’s why I think so many Catholics have lost the meaning of the Mass, even many priests, sadly.

What an absolutely stunning insight! And astute observation. Yes, the Catholic Church is the Jewish faith that accepted Jesus as the promised Messiah. If you read the writings of the Early Church Fathers, you see Jewish and Catholic but not a Protestant in sight.

I’m always amazed at how the Holy Spirit can show even *this dummy* such insights. 😉

In my pseudo-Catholic parish, they have adopted the protestant “Alpha” program as THE primary focus of parish life

It was also announced Sunday at Mass that the recent Perpetual Adoration program was being curtailed due to lack of Adorers.

Is it any surprise? In the recent renovation, the Tabernacle was removed from the Sanctuary and placed at the BACK of the Nave, where everyone sits with their backs to the Lord, and 99.9% never acknowledge his presence entering and leaving the Nave – EVEN AND ESPECIALLY THE CLERGY.

So sad to hear. I assume you are not within drivable distance to an FSSP parish, or one that is more reverent to our Lord? I imagine your Liturgy is not very reverential as well.

cs (below) is right. Please look for a more reverent Novus Ordo Mass if you cannot locate a Latin one. I had to look at many parishes when our new priest began preaching another gospel, but I found one where the (foreign) priest knows the Mass is the same Sacrifice of Calvary and he teaches the True faith, thanks be to God. It’s well worth the extra drive!

We “church hopped” for a while when we moved to a new state in order to find the best parish. We wound up choosing one with a traditional priest, who offers the Novus Ordo reverentially, uses the Roman Canon on all Sundays and Holy Days, and says the Prayer to St. Michael after Mass. Turns out, he also offers the Extraordinary Form monthly at the Cathedral.

I don’t want to church shop. I want what is mine by right…the faith of my fathers.

I want what was taken from me and my children, and I don’t want to drive an hour and a half when there is a Catholic parish less than five miles from my house.

I want my pastor to actually be Catholic, and not a protestant, mega-church wanna-be celebrity / comedian / late night talk show host.

This is our right! It was given to us by Jesus Christ!

Yes, that would be nice. But since when has the Will of God been what WE wanted?

Your comment suggests that God’s will is that the Roman Catholic Church be further protestantized, and that we should accept it and follow the multitudes towards the gates of hell.

I don’t suspect that is your intent, but it is what your comment suggests.

Jesus Christ did not found a church with coffee shops, rock bands and projection screens. He founded a Church focused on the Sacrifice of the Mass, and I’m not willing to let that be taken any more from me.

Perhaps it is God’s will that our current lukewarm faith be vomited from the Lord’s mouth – if that is, so be it.

I will still pray for a return to sanity, to right worship, and for a Christ-focused liturgy.

Obviously God willed what has happened to the Church in the last fifty years, perhaps as a chastisement, otherwise it wouldn’t have happened.

Gold must be purified in fire. The souls of the faithful are more precious that gold. Each must be tested, and tempered, and purified, to withstand the trials yet to come.

That which does not kill you (the eternal death) only makes you stronger. The gift has been squandered by many. We are now being prepared to receive it more fully again. There can be no perfection without the complete detachment from sin. We are experiencing part of the “purgatory” of the Church. It must have the dead wood whittled away, in order to be prepared for the next steps.

Cetera, You got it right. I am with you and agree 100% From — Michael Long. E-mail is — underourmothermarysmantlegmail.com

My E-mail is [email protected] THANK YOU. From —- Michael Long

No. God can will nothing evil. His permissive will can allow evil, for instance for our correction, and because He is Almighty he can draw good out of it. But the evil comes from the broken nature of Man.

Correction:

The faith is a gift, freely given by Jesus. That gift was squandered. It is your right to accept or reject the gift, but the Lord is under no obligation to give it to you. He chooses to do so freely, without reservation.

The Church as a whole has squandered many graces and blessings, and cheapened the outward physicality of the gift that was given to all of us. Never-the-less, your faith, such as it may be, has been given to you freely, as has your life, your senses, and all other things you identify as you. All given, but none earned.

To quote Tolkein again, “So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All you have to decide, is what to do with the time that is given you.”

Good grief.

Ok then, I am glad you were here to correct me.

It is an important distinction. The failure to understand that distinction is one of the root causes you don’t get to celebrate the faith of your fathers.

There is a distinction that you are totally missing in your effort to be ‘right.’

Guess what? You get to be ‘right!’

Have a nice day!

*sigh* You as well.

ALPHA is not good! Somebody’s just making $$$$ on this protestant-ized program!

Alpha is free and does not contradict Catholic teaching. It is a great resource to help people encounter God and become part of the Church. It must be followed by catechises, of course.

Ma’am, you simply are ignorant about Alpha. It is NOT free. It is a trademarked program that parish’s are NOT free to alter in any way. They have to buy it hook, line and sinker, and it is EXPENSIVE.

Alpha does in fact contradict Catholic teaching by specifically leaving it out. In the “ALPHA for Catholics” program, there is brief lip service given to only some of the critical, crucial, central Church teaching AT THE END OF THE PROGRAM. It takes a back seat to charismatic “praise and worship” and all that stems from that.

I took the time to extensively research it, before telling my pastor that my children would NOT be enrolling in the ‘mandatory’ program which was replacing the religious education program at my parish. You should do the same.

I’ve run alpha youth in a catholic context and attended alpha courses. You can choose to buy the stuff or you can use their YouTube videos. Alpha International spends its money well, so even if you end up paying for booklets and videos you can be confident that they are doing the Lord’s work.

Cardinal Tagle spoke at this year’s Alpha Leadership Conference and so did Fr James Mallon (his book, Divine Renovation is excellent). A few years ago, Fr Raniero Cantalamessa was one of the speakers too… none of them would have agreed to speak or recommend the resource if there was a problem with Alpha.

Archbishop Wilton Gregory of Atlanta also heartily endorses the Alpha program – that should tell you something.

If you’re OK with our Church throwing out more of our tradition in favor of protestant practice that has brought us this horrible mess we’re in now – so be it.

Some of us want to actually be Catholic. We want was taken from us – what Jesus gave us.

There are a million and one protestant churches and programs to choose from.

I choose Roman Catholicism.

Cardinal Tagle!!!

Fr Raniero Cantalamessa!!!

Both virtual Pentcostalists! By citing them, you damn the Alpha Course 100%.

Cantalamessa, the Papal preacher, has taught explicit heresy.

WRONG!!!

It’s NOT CATHOLIC!! It’s PROTESTANT!

It is not a protestant-ized program….it is a protestant program.

It is a protestant program that only focuses on ‘the things that Christians can all agree on.’

It is worse than ‘not good.’

If one wants to worship in a protestant church, by all means – go be protestant, but leave those of us who actually want to be Catholic in peace.

You are correct to note the “$$$$.” It is not a cheap investment – it is a money making machine…simply look up their website and go to the ‘store.’ where you can find all manner of coffee mugs, t-shirts, etc.

Thank you. I wasn’t very good at explaining myself. You were better!

I’ve watched EWTN from its inception. I don’t recall any of the televised Masses being offered ad orientem.

They were toward end of 1999, but it didn’t last long after that. I remember Mother Angelica was very angry because the new bishop forbad it. A couple years ago, a priest who knows people at EWTN said that it was so the cameras could capture things better, or something to that effect.

As I understand the situation, the bishop forbad the televised Mass to be celebrated on television. Bishop Baker, who has been bishop of Birmingham for about ten years now, has continued this policy.

Found this article dated Nov. ’99

natcath.org/NCR_Online/archives2/1999d/111999/111999g.htm

I recently made reference to Fr. Meagher’s 1906 book, How Christ Said the First Mass, in another context. This book makes a painstaking examination of the Jewish liturgical roots of the Mass. It is absolutely incredible. The notion that early Christian worship was simple and primitive, maybe something like Protestant “praise and worship” with yarmulkes, is totally wrong. As RB noted above, there is a close and recognizable link between the Jewish and Catholic rites. When Benedict was being inaugurated, I had a TV on in the kitchen, but I wasn’t watching, only listening. Suddenly I heard some chanting, and I thought, “Rabbis are taking part in the papal installation?” It turned out to be a group of Chaldean priests, those of the oldest rite. It sounded absolutely like Jewish liturgical chant.

Hold on what about Ad Orientem that did that?

My mass has all those things still 🙂 Check out St John Cantius if you’re ever in Chicago

Lots of places have latin Mass. Check out http://www.ecclesiadei.org/masses.cfm

Also, not a fan of St. JC, purely because they like to mix Novus Ordo with the TLM almost as though they are trying to curry favor from the liberals in the Holy See.

It’s not a matter of trying to “curry favor” with anyone. It’s more a matter of offering a choice of two legitimate rites.

Thanks for the link, but for the most part an idiotic post.

St John Vianney in Northlake is similarly excellent.

What about the lack of liturgical abuse? Latin and the RUBRICS effectively stop abuses during the Mass.

That’s why the liberals falsely said that Latin was not allowed – it would spoil their plans. Read the works of the late, great Michael Davies. They’re available at the Remnant, Angelus Press 1-800-96-ORDER, TAN Books 1-800-437-5876 or even in used book stores. Check around.

There were plenty of liturgical abuses in the Middle Ages when Latin was the norm.

Knock it off Thomas. Abuses in the middle ages were departures from the norm.

The Novus Ordo has built in abuse at its core.

I think you know the difference, but have chosen which side you are going to defend. You are on the wrong side.

Most liturgical abuses are things for which the Council never actually called.

But by all means, continue your hysterics

Have you actually read Sacrosanctum Concilium? Or are you just repeating what you’ve learned from newchurch apologetics?

I haven’t read the document. Care to provide an explanation and/or response of how the Novus Ordo is inherently liturgically abusive?

Why don’t you read it first and see how ambiguous it is?. Or you can just quote the party line, which you have done without reading it too. It’s up to you.

You can read it with a conservative bent, a very liberal one, or a spectrum of interpretation inbetween. It was deliberate. They said so themselves. Bugnini drafted it, and then by a twist of fate got to implement it.

Just read it. In this age of the internet, there’s no excuse, if you want to know what happened to the Church and consequently how to protect yourself, you need to be informed, and there has never been a time in history when this was so easy to do. I firmly believe that God allowed the internet for this purpose.

I’m a convert, too (2014), and the more I learn about how things used to be, the more I wish they were still that way.

If you want to see what Catholicism is like, then look for a Society of St Pius X (SSPX) chapel near you. They have kept everything intact, including the traditional rite of Holy Orders.

Some people may try to scare you off them, but St Paul says (God says) to “hold fast to tradition”. We have no business messing with anything that is not from tradition; this includes ALL the Sacraments, and the Mass.

There is enormous symbolism in the clergy turning their backs to God, and turning towards the people.

The reality of that hits home like a hammer to the temple.

We have turned away from God, and towards each other….

Precisely! The religion of God was put aside, and the “cult of Man” (to use Paul VI’s own phrase) was made front and center. They even have the gall to call it the “Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite”!

As a recently confirmed teen, I cannot express how overjoyed I was to finally receive the sacrament of confirmation, as it meant I could finally start attending TLM regularly. I went to my first Latin Mass in January and after leaving, I remember feeling very displeased with how I had been robbed by the New Agers of this beautiful and holy sacrifice. I have also been teaching myself the Latin Altar Boy prayers so that I might be able to serve Mass someday

Now you can truly pray: Ad juventutem laetitiam meam.

Keep at it!

Thank you, Pax Vobiscum

You missed the best part, the start, “I will go unto the Altar of God”

Curious question, what was stopping you from assisting at Mass in the TLM before your confirmation?

My parents forbid me because they don’t like the Latin Mass, and also, since I was not confirmed, I technically was not a full member of the church, but since this has changed, they’ve relaxed their grip on where I go for mass. Fortunately, the closest Latin Mass is only 19 minutes from my house, at Church of the Sacred Heart in Robbinsdale

Congratulations to you on your confirmation!

Thank you!

@DeusVult76, Your Baptism did not make you a full member of the Church? I need an explanation of this term, please. An unconfirmed Catholic is a member of the Body of Christ by virtue of his Baptism; I don’t think there are degrees of membership. There are certainly degrees of maturity as Christians and the Sacrament of Confirmation provides the Gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord.

I just don’t remember ever hearing it put this way and I am old enough to have memorized the Baltimore Catechism. I hope it isn’t some Protestant clap-trap like needing to be born again (thanks, I got it right the first time) that has crept into Catholic catechesis.

Anyway, DeusVult76, congratulations on your Confirmation and on discovering the Latin Mass.

Sorry, I mean a permanent member of the Church, sealed, locked in for life. I see this as having a more mature status within the church and a greater opportunity to expand my devotion. Sorry if I caused you confusion

DeusVult, Donna is correct in two most important respects: 1) Baptism is a Sacrament which cleanses us from original sin, makes us Christians, children of God, and heirs of heaven (as we used to say), and 2) it is a permanent, irrevocable act which effects a permanent change upon the soul of a person.

Yes, this is true, thanks for the correction. I guess what I am trying to say is that I feel more mature in my acting as a part of the Church. I’m sorry if I did not state this clearly

No worries. You are still in the early years of a lifetime exploration, a journey, and no one begins at the end! What is important is that you apply the energy life grants to the young, as it seems you are doing, and to remember always that it is God who initiates, not you – it is for you to respond. Let He who draws all things to Himself, call you! In Christo.

You were sealed and locked in for life with your Baptism. With your Confirmation you have indeed attained a more mature status and every reception of the Sacraments, every visit to the Holy Eucharist, and every moment of prayer during the day is an opportunity to expand your devotion. As we pray in the Anima Christi: Soul of Christ, sanctify me. What can this mean except that we think and love as Christ thinks and loves? Have a wonderful life!

Thank You! I’m sorry if I keep butchering my words, sometimes you know what you want to say in you’re head but it exits like a ton of bricks

You are doing a great job! Just keep reading, praying, thinking, and writing.

Son, your young *voice* is music to my ears and answer to my prayers. God bless you and keep you strong in the faith. May there be millions more like you!

Deus Vult, God wills it

Wow, you are awesome. God bless you. One word popped into my head when reading this: PRIESTHOOD.

God may be calling you, young man. Keep your heart open. We need soldiers like you!!!

hangar

People who receive on the tongue must learn to shut their eyes, out their head back, and extend their tongue flat. Almost all people who receive on the tongue keep their eyes open, and watch the host, and try to “help” the priest by moving their head forward, waggling their tongue to “scoop” up the host, etc. They often end up licking the priest’s fingers. Which is unsanitary. What the priest needs is a motionless target.

Thank you Arthur, I am a revert and thought that we should let the body of Christ dissolve.

Good grief. Were all my childhood communions not received because the sisters told us to let the host dissolve? ai yi yi

If that’s what the approved theologians say, then yes.

Well, things can enter the bloodstream through the lining of the mouth; I wonder if that counts. I’m hoping. https://biology.stackexchange.com/questions/7019/what-nutrients-can-humans-absorb-in-the-mouth

What really blew me away was when I learned that the documents from VII did not call for any of this!

Vatican II did not call for;

1) Communion in the hand.

2) pushing the altar back from the wall and making it a “table for the Lord’s supper.”

3) Versus populum (towards the people)

4) Communion in the hand

5) insipid music

6) Communion in the hand

7) Altar boys that are girls.

8) Removal of Latin

9) Communion in the hand.

We’ve been had by the “Spirit of VII” folks. But the joke is on them due to the mass apostasy.

Well, Vatican 2 DID call for increased use of the vernacular in Sacrosanctum Concilium but not a total abrogation of Latin.

Right. Which is why I wrote that. There is a total removal of Latin in a majority of Novus Ordo Masses, something not called for by Sacrosanctum Concilium. The first and only document from VII that dealt with the sacred liturgy.

Hi Vortex

All of your points get on my nerves especially “Communion in the hand”

Were – Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion approved by VII? Also, I don’t know the name of the part of the mass that occurs after the homily but it is when a layperson goes up and reads different prayers and we respond “Lord hear our prayer” Both of the above should be given the boot!

No. Non consecrated people were not allowed to touch the sacred Host so there were no EMHC. All that happened after the 2nd Vatican Council.

That part of the Mass is called the prayers of the faithful.

Thank you immensely VV,

The EMHCs always send a shiver down my spine. We recently went to a mass in my Father’s parish and the mass didn’t have the prayers of the faithful. We went straight from the homily to the liturgy of the Eucharist. It was much better and we had the sense of fluidity as to where the mass should be going. My wife and I wondered if this was a VII change.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Vatican II document on the sacred liturgy, was drafted up by none other than Anibale Bugnini. If you don’t know who he was, then look him up!

The document is so disgracefully ambiguous, and intentionally so, that it allows for a whole host of interpretations. The late Michael Davies called these ambiguities “timebombs”.

You can read the same text with a conservative bent, or a completely modernist and progressive bent, and get an entire spectrum of opinion in between on what it “really” means. It’s a masterpiece, actually.

Bugnini was also the man appointed by Paul VI to head the group, Consilium. Consilium were responsible for the implementation of SC, and they produced the Novus Ordo Missae in 1969, which was officially approved by Paul VI himself.

All the things in your list were approved either by Paul VI and/or John Paul II.

Unfortunately, many Catholics today do not even realize they have been robbed, literally robbed, of the beauty, the sacred music and reverence, the way the Mass is supposed to be, according to what the documents of Vatican II actually say. The mis-interpreted, mis-implemented novus ordo is all they know and all they have experienced. Beautiful OSM pic at the top.

I listened to a teaching on youtube from Sensus Fidelium a week or so ago and the priest was explaining how the NO doesn’t have the symbolism of the Jews converting as the TLM does. It was a very interesting talk. If you haven’t discovered Sensus Fidelium I would strongly encourage looking into it. I know the one priest who teaches is Fr. Philip Wolfe, FSSP and he is outstanding. Here is the link for the conversion of the Jews. It’s an hour long, but the portion about the Jews is the last 20 minutes. Enjoy: https://youtu.be/4lVzYaiBe1g

My absolute favorite though is this one from Fr. Wolfe, St. Anne, the miraculous discovery of her relics: It’s only 18 minutes, but it positively a don’t miss teaching…so very edifying. https://youtu.be/ywWymmRnio0

I mourn the fact that in many parishes, most of the nine things listed have been lost to a good number of Catholics and it will take several years for the nine to be reintroduced by the orthodox young priests who are doing just that. This is a sign of hope for us which I’d like to point out to those who have commented thus far. I’d also like to remind those who have commented about Msgr. Klaus Gamber’s book, “The Reform of the Roman Liturgy: Its Problems and Background…” and state that even he said that the Tridentine Rite needed reform and went so far as to say that the 1965 Rite that came out of Vatican II was beautiful and should have remained THE Rite for all the Church after the Council and never should have been changed. I said that if it had not been replaced, we would not have had the problems we’ve had since then. Hence, his solution: Start with the Tridentine Mass — the Extraordinary Form of the Mass — make the necessary changes and give that to the Latin Rite world as the Mass to be offered with no exceptions.

My point here is that even Msgr. Gamber — a friend of then Cardinal Ratzinger — who was a true liturgist with a knowledge of the liturgies of the Latin and Byzantine Traditions (West and East) knew that changes were needed in the Tridentine Mass. Therefore, the idea of an “immutable Canon,” is incorrect. I am an orthodox priest with very conservative views and I have a love for the Extraordinary Form of the Mass, but I also love the authority that Jesus Himself gave to Peter (and the other Apostles later on, hence, the Church’s Magisterium) when He said to Peter, “Whatever you bind on earth is bound in heaven and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” Peter Too many orthodox Catholics today forget the scope of Peter’s authority and, therefore, they forget that if Peter says that the name of St. Joseph is going to be added to the “Roman Canon,” now called Eucharistic Prayer I, then Christ says the same and why? Because of those other beautiful words Jesus spoke to Peter first and then the other Apostles, “He who hears you, hears Me. He who rejects you, rejects Me and rejects Him Who sent Me.” How often I have heard allegedly orthodox Catholics, who are good people, denouncing this or that Pope, even if the Pope is a saint, because he had the audacity to allow altar girls (I didn’t like it, but the Pope had the authority from Jesus Himself to change a discipline and hopefully the next Pope will change it back), or to limit the number of times we kneel during the Creed at Mass. I heard people speak almost with contempt when Pope St. John Paul II added the Luminous Mysteries to the Rosary. “Who does he think he is?” one woman asked sharply. “He knows he’s Peter,” I responded. What these people, even here, and I haven’t read through the comments so I can’t speak generally, are doing in condemning Peter is condemning Christ Who speaks through Him. What will they say to Jesus when they stand before Him as they pass from this world to the next? It is not a light matter!

So when Peter in the person of Pope St. John XXIII called Vatican II it was Christ Who called the Council, and when Bl. Pope Paul VI signed the document of the Council adding three new primary Eucharistic Prayers along with others to be used on special occasions, it was Christ Who signed that document. The translations were very poor I’ll grant you that much, but it was within Peter’s power to give us four main Eucharistic Prayers and to give us a three year cycle of Scripture readings for our Sunday Masses.

On this topic of the Sunday Scripture readings, I have a hard time understanding why anyone would have a problem with more of God’s word in the Old and New Testaments being read to us each week. How can one be angry that one is hearing more of Our Lord’s soothing words at Mass rather than the same words every year? For the record, I’m a product of the Extraordinary Form of the Mass, the 1965 Rite and the many changes of the Ordinary Form with all the frustrations that went with them. However, I’ve also seen how beautiful the Ordinary Form of the Mass can be when it’s offered as the priest follows the General Instructions of the Roman Missal and the Rubrics of the Mass faithfully, i.e. Ad Orientem, and with sacred music.

To all of you who are yearning to have back the nine things we lost that were mentioned in the article, I yearn to have them back as well in more parishes. We have almost all of the nine where I come from, but one is still missing and I’m hoping we can implement it in the near future.

For those who have suffered because they’ve endured flat or disrespectful or even scandalous Masses, I can empathize with you because as a young priest I had to endure such horrors that I’m glad I’m where I am now with a good group of people who want Holy Masses, Catholic preaching, and all the nine things mentioned in the article.

I have no animosity toward those who expressed their views, but I ask that those who have anger in their hearts about what we’ve lost to beg God to restore it and to remember to pray for our present Pope, bishops, priests and deacons. If you’re one of those who complains about things you see that are wrong, but you never pray for one of the cleric(s) committing the liturgical sin, then you’re not helping him/them toward conversion and you’re not helping yourself toward sanctity.

I will close my comments by saying again that there is hope for the Church in our young priests who are fighting hard and effectively to bring beauty back to the Mass and to our churches. They’re fighting hard to teach the Faith as Christ wanted it to be taught and slowly we’re seeing those who helped destroy the Faith in so many be replaced by “other Christs,” who are winning people over to Christ again. Please pray for our young priests, pray for all orthodox priests that we may remain steadfast in the midst of persecution and be given the grace to knowledge of how “to restore all things in Christ.”

It was Christ Who gave us three badly-translated (“I’ll grant you that”) variations on the Canon!

HAHAHAHA!

Mate, you have to be joking.

You say you are “very orthodox”. Then you will know that the scope of “Whatever you bind on earth is bound in heaven and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” has always been considered to be an authority to be used very, very carefully indeed: and certainly not to initiate Modernist Revolution, decimate the faith of the Catholic people or any other abomination.

This is the insanity of the liberal and Modernist. They regularly trot out this verse to tell us that God (in Whom most of them don’t believe) supports whatever outrages they care to enact next.

+ In response to your assertion that Christ gave us three bad translations, the correct answer is that Jesus, through Peter, in the person of Bl. Pope Paul VI, gave permission to have three extra Eucharistic Prayers. Fallible bishops and others gave us bad translations. Jesus, through Peter again, after requests from faithful bishops and others for better translations, remedied that situation.

As for Peter using his power to bind and loose, you are correct in that he uses it carefully, but remember that Peter is not bound to consult the bishops, priests or laity before he uses that power.

Regarding Vatican II, may I ask you where in Sacred Scripture Jesus said that the Power of the Keys would one day pass from Peter to the laity? I ask this because your “infallible pronouncement” that Vatican II was not a valid, true Ecumenical Council certainly sounds like you believe you have the Power of the Keys and know something that Jesus Himself and the Vicar of Christ, in the person of Bl. Pope Paul VI didn’t know since they proclaimed it valid. Have you read the Council’s documents? In which document do you find a break with Tradition? In which document do you find Modernism? I studied Modernism formally and in depth, so I can tell you with great conviction that you won’t find a hint of Modernism in Vatican II.

Finally, how is it, my friend, that you expect to achieve credibility with a username of “The Great Stalin,” unless that’s your real last name? If so, you may want to let people know that when you comment, but if it’s not your own family name, take some advice and distance yourself from one of the Church’s greatest enemies.

I made no claim to have made an “infallible pronouncement”, so we can I think safely discount the rest of your post.

I have submitted a three-part article on the Novus Ordo to 1P5. If published, it will more than answer your ridiculous assertions.

+ May the Sacred Heart of Jesus be in this discourse. Your comments this time only show my point that you assume you have the Pontifical right to determine the validity of Vatican II, but you went further this time into gravely sinful waters when you call it ” that hell-damned council.” All I can say to you at this point, you very unhappy man, is that I will pray for you because you believe yourself not only more holy than St. Peter himself, but more holy and self-righteous than anyone. May God have mercy on your soul.

Silly sod. The Council cannot be one that binds: the result of the Synod of Pistoia was that the then Pope ruled that no Catholic can be bound by ambiguous documents. There are several key Vatican II documents which are nebulous, indistinct. Therefore, no Catholic is bound by them.

Watching Mother Angelica’s funeral showed me that the Holy Mass as V2 supposedly meant it to be is awe-inspiring and heavenly. Thank you for your efforts, Father, and never ever give up!!!

I feel that this argument has been used to excuse the mass apostasy since the introduction of these innovations. While what you say regarding Peter’s authority is right, men also have free will. The outright rejection of Paul VI’s order to the bishops of Holland, Belgium and Germany to cease reception of communion in the hand should have given the pope cause to remove them and put them in obscure positions. That would have sent a clear and distict message. But he didn’t. And here we are.

The sheer numbers of priests, religious, and lay faithful that has left the Church established by Christ since the innovations have been installed and not come from God. As we do know, He allows evil that good may come from it.

God bless you Fr.

+ Thank you for your heartfelt response. If it is any consolation to you, I know that Bl. Pope Paul VI regretted allowing the innovations that he did after Vatican II and he suffered greatly because of the decisions he made early in his Pontificate. Those decisions, however, do fall under the Power of the Keys, but thankfully not under the charism of Infallibility. It is no secret that Pope Paul was a little progressive when he became the Successor of Peter, but not so much that he took the heretical advice of those who wanted him to change the Church’s teaching on contraception. Thanks be to the Holy Spirit Who gave Pope Paul the fortitude and sound words to write “Humanae vitae.”

I truly believe what you said Fr. Frank re: pope Paul VI. Both Humanae Vitae and Memoralie Domine which specifically addresses Communion in the hand. You can tell he did not want this practice to spread.

“On this topic of the Sunday Scripture readings, I have a hard time understanding why anyone would have a problem with more of God’s word in the Old and New Testaments being read to us each week. How can one be angry that one is hearing more of Our Lord’s soothing words at Mass rather than the same words every year?”

Let me try to explain why I, at least, have such a problem. The Catholic Mass is worship. It is a holy sacrifice. The Scripture should complement the sacrificial nature of the Mass. When reading is piled upon reading, there is a tendency for worship to morph into instruction. This gives the Mass a Protestant flavor. As for the same words every year, nothing has made Scripture more meaningful for me than this frequent repetition which makes the carefully selected passages sink into my soul and my memory. Only one who looks for some kind of entertainment value in the Mass who would find this repetition tiresome. Anyway, as I once said to a friend who was speaking enthusiastically about the additional readings of the NO, the EO is itself constructed overwhelmingly from Scripture, everything except for the impetratory prayers is Scripture. It is the warp and woof of the Mass.

On the contrary, most of the Introit, Gradual, Collect, Offertory, Communion and Post-Communion are taken from the Psalms and other Scripture.

Thank you!

There is no Offertory in the new mass. The Offertory is one of the three essential elements of a valid Mass. (Offertory, Consecration, Priest’s Communion)

Assuming you have valid Holy Orders, how do I know you intend to do what the Church does when you use the Novus Ordo Missae? I need to know that a Sacrament is valid before I can approach it.

This new mass is extremely ambiguous. What theology does it represent? Protestant or Catholic? Both? Neither? It supresses the Catholic truths it is supposed to affirm. Most importantly it suppresses the notion of the renewal of Our Lord’s propitiatory Sacrifice of Calvary. It can neither be pleasing worship to God, nor does it cause the priest to manifest the intention to do what the Church does, for a valid consecration.

There is also one more point to be made. Where did Paul VI make it binding? Where did he excercise the power of the Keys of the Kingdom, so that we could know that it was approved by Heaven? Nowhere. I never go to the new mass, and by God’s grace, I never will again.

What we have lost is the entire Catholic sense of the divine. That’s it in a nutshell.

Good friend, why do you have such contempt for the Bride of Christ? I will admit that the battles those of us who are Orthodox in the Faith have fought have sometimes been brutal. I will admit that “blind guides” and “whited sepulchres” in the the Church have sought to lead many astray, thinking they are doing God’s will. I, as a priest, have done fierce battle with these clergy and laity and have seen what you as a layman will never see because of my state in life. However, my battle wounds have only left me loving the Church more and wanting to fight more to see that what good was meant to be implemented by Vatican II is implemented.

You, it seems, suffered a wound that has made you distrust Christ’s Holy Bride and because of this your vision is clouded so that you see what is not present, don’t see the good that is and you distort what is still beautiful because someone out something has hurt you very deeply.ause

It’s far too late for any Auntie or Uncle-style calming down and everything’s-all-right-dear mogadon. The enemies are within the gates and instead of mogadon we need swords.

Start connecting the dots!!!!

If the Novus Ordo smells, looks, sounds and feels protestant – then IT IS.

I. Will. Not. Be. A. Protestant.

The new liturgy effectively removed the sense of God and replaced with the celebration of Man. Now where do we go to find a power greater than ourselves which is what the Church and Mass is supposed to be about. The baby went down the drain with the bathwater.

Most importantly the we lost the offeratory and all the distinctly sacrificial language especially describing what the mass is, a sacrifice in propriation for our sins

Personally I think these are most important:

1) Ad orientem

2) Altar boys ONLY

3) Altar rails and reception on the tongue

4) Ban all Extraordinary ministers of holy communion and only clergy should distribute holy communion

5) Gregorian chant

6) regular use of incense at each mass

7) Restoration of the Roman Canon as the only eucharistic prayer allowed

I have seen the Ordinary form done well before andeciding if done well birthday. Ally with all these in mind, most people would not have a problem with the liturgy I think.

The addition of these things does not change the protestant-ecumenical nature of the Novus Ordo.

Good list.

I would place reception on the tongue while kneeling as #’s 1-5. Then the rest will follow.

The Eucharist is the summit and source of our faith for a reason.

Yes I think you are right about 1-5

Even were you to put all these nice trappings back (to make it look, you know, like something Catholic) the essential character of the novus ordo would still be a defective rite, in that it suppresses many, many Catholic points of doctrine. The most important of these is that the Mass is the very renewal or re-presentation of the Sacrifice of Calvary.

If you study the Novus Ordo Missae in any detail, you can see that the inventors of this new, synthetic rite systematically and deliberately suppressed essential Catholic truths, to make it in line and compatible with a protestant Lord’s Supper service.

Acts 20:28 says that Our Lord “purchased the Church with His own blood”. Jesus shed His Precious Blood to bring the Church into existence.

He founded His Church so that it would “teach all nations” all the Divinely revealed truths he wanted to be known. So when this new mass suppresses those truths the Church is meant to proclaim until the end of time, it spurns the Precious Blood.

By God’s grace, I will never attend it again.

During the consecration in the TLM, the following occurs;

The priest genuflects and adores the Sacred Host.

He elevates the Body of Christ for the veneration of the faithful.

He places the Host on the corporal, genuflects, and adores Him again.

In the Novus Ordo, the priest only genuflects *after* the Body of Christ is elevated for the veneration of the faithful, just like in the Lutheran service, because the host only becomes the Body of Christ after it is venerated by the people.

I’ll stick with the TLM…

And we should talk to the Orthodox about fasting. Or rather, listen to them. Before the Deformation, whose insights we are so merrily celebrating, everybody from prince to ploughboy fasted. Now, we have forgotten we ever did it.

The Catholic Church won’t recover till she recovers fasting.

The Orthodox basically eat vegan, and no alcohol, for what adds up to about six months out of the year, between Advent, Lent, and many individual days of fasting throughout the year. It is really challenging. How weak and flabby we Catholics have become by comparison!

Hey, don’t forget about the Eastern Catholic Churches! I’m Ukrainian Greek Catholic but have cousins who are RO. I tried keeping the traditional fast this year and it was TOUGH.

No meat after Meatfare Sunday.

No dairy products after Cheesefare Sunday.

http://www.royaldoors.net/2017/01/fasting-abstinence-rules-prescribed-ukrainian-greek-catholic-church-2015/

A religion without bodily engagement is a theory. Fasting is essential. It is not a negotiable. I am becoming convinced of the concrete necessity of returning to the three hour fast before Holy Communion — and I’m thinking the previous fast of “nothing after midnight” might be preferable.

I remember when Friday abstinence from meat was cast aside for “some act of penance” — I was in junior high school, knowing full well it was the beginning of a catastrophe.

A dumb adolescent could “read the signs of the times” but our wisdom figures in the episcopate were clueless. My peasant Irish grandparents knew what was going on, but the bishops couldn’t foresee the consequences of their deficient perspective.

Or maybe they could…

Atheism in a cassock.

Same here.

Excellent article that nailed the main issues before pew – sitting Catholics of that era. As you say, these each seem to be small issues, but taken together communicated something powerful and deadly. As I related to my Pastor 10 years ago, my experience growing up Catholic in the New York culture of the 1960s and 1970s – everything around me (friends, neighbors, TV shows, newspapers, celebrities, sports, public school, music, etc.) told me this “religion thing” was no big deal. Not very important to my life. And it seemed to me as a teenager that, with each of these changes, the Catholic Church seemed to be saying: “They’re right – no big deal”. I have since learned better. Has the Church?

I’m thankful for the vernacular, since as a convert I don’t know Latin. The Catholic Church prior to the Council of Trent and finalization of the Tridentine Rite had many Masses and rites in the vernacular. The Orthodox Christians have always emphasized use of the vernacular, so people can really participate in the liturgy, though the situation is a little bit different in the US due to so many immigrant churches, where they still use a lot of language from their home countries.

What I object to is the watered-down prayers and scripture translations, and dry as dust, uninspired plain English, as if there is no great English literary and liturgical tradition. The English translation in the Tridentine rite missal is beautiful, why couldn’t they have just used that, and made no changes? And adapted Gregorian chant to English plainchant?

I also would l like to get rid of pews, a Protestant invention. Prior to pews Catholic worship was much freer, standing, prostrating, etc. as people felt moved to, not regimented. Most Orthodox churches have no pews and conduct worship standing, which is much more engaging, including of the body. No sitting around passively while your mind wanders. Some have chairs so people who are old, sick, have bad backs or whatever can sit as needed, but the norm is to worship standing.

As a visitor I often attend a local Antiochian Orthodox Church (Antiochians have been the most open to US converts, entire congregations of Evangelicals, Episcopalians and others have converted, and the one near me was founded by an Episcopalian priest and his congregation). The liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, and St. Basil in Lent, is stunning. All in traditional, King James-style English and mostly Russian Orthodox style polyphonic chant, only a little Eastern Syrian style here and there, mandated by the bishop as easiest for Westerners and Western ears to worship in. The entire congregation chants along with the choir, and polyphonic chant makes that easier, too, as voices can sing in their own range if they know how to read music, which is provided to the congregation. I love singing the soprano line while standing next to an alto or bass. It makes the congregation part of the choir, and the priest leads the worship facing away from us to the altar and God, leading us in crying out to God. It is incredibly moving and beautiful, completely unlike the Novus Ordo Mass where I am often bored, irritated by how badly everything is done, and have to really work at it to stay focused on prayer.

I can of course pray deeply during the Novus Ordo, but it involves tuning out all the plainness and silliness going on around me. The Divine Liturgy however just sweeps me up and I don’t have to tune anything out or try at all to pray. It just carries me along. The Catholic Church should take a page out of their book – and get back to it’s own tradition of beautiful, chanted, standing worship in the vernacular. That is the key to real participation of the laity, as I am learning from the Orthodox.

Good thing that all those things (with the possible exception of #9) can be incorporated into the Ordinary Form of the Mass and actually have never really been taken out.

For example, I kneel for communion and receive on the tongue. I bow my head at the Holy Name of Jesus. I attend the 6 p.m. “College” Mass at our parish (which is the chapel for the local University) and there are only male altar servers.

From the experience of going to mass in France, I can say with confidence that what being Catholic means has been lost.

Many of the things that the author mentioned in his article exist within our parish and I’m grateful for these things but Catholicism as a faith rather than a hobby is missing.

The joy and enthusiasm to be Catholic is rarely seen.

The irony is that the US is probably more fervent in Christianity than France, it being part of the growing secular Europe, despite the US being immensely affected by VII. I suppose the “smells and bells” can help, but only to a degree.

Dear GRA, Thank you for the explanation it helps me.

These abuses only exist because the Catholic heart of the Mass was ripped out. Look no further than the Novus Ordo, itself the greatest abuse and the one which facilitates all the others.

You’re on a roll, Joe! Great posts all round!

Fraternal socialist greetings Comrade and thanks.

In our diocese we have, as a matter of POLICY, the tabernacle moved away from the altar, no statues (in order “not to distract from what is going on at the ‘table'”) in front where the congregation can see them (they are relegated to behind the congregation in a dark corner), no incense ever, and reverential silence is not allowed – we get to listen to 15 minutes of synthesizer, which is an assault on the ears, so it’s impossible to recollect one’s mind and heart for what is about to happen. No one actually genuflects properly; they give a ‘sort of’, halfway genuflection, or bow slightly to the altar, but walk right past Jesus in the tabernacle. While the Lincoln, NE diocese is an oasis, the Davenport, IA diocese is a desert. What happened in ancient Israel has happened again – they didn’t want to be a people set apart, they wanted to be like other nations: 1 Samuel 8

“19

But the people would not hear the voice

of Samuel, and they said, Nay: but there shall be a king over us,

20

And we also will be like all nations:

and our king shall judge us, and go out before us, and fight our battles

for us”

And like the Hebrews of old, the way of thinking and acting and believing of “other nations” has infiltrated into the Church, and we are left corrupted and starving and enslaved by evil.

Man that sounds AWFUL!!!!

Well the paten isn’t gone but the Altar Rail is. I have never received in the Hand as Post-Vatican II baby, I still bow my head at the Holy Name of Jesus. But this is no longer taught as vocations of Religious decline and Catholic homes falter under worldly influence. We still bow our heads/bodies at the reference to the Incarnation in the Creed. We continue to genuflect towards the Blessed Sacrament upon entering the Church and the Presence of God but many younger ones may not.

A small correction Eric you have a slight error there Eric. In the Tridentine missal we did the sign of the cross at every mention of the Holy Trinity and in reality even at the Novus Ordo I still do.I believe it was perhaps around thirty times for the priests. We beat our breast at every Have mercy on us in the both the liturgies and the litanies. Christ led the Jews out of Limbo and the priests lead us or should do to the Christ on the altar who promised us when raised up I will draw all souls to me. We were also taught to receive Holy Communion and not use our hands and not to touch it with our teeth. The corruption of old food decaying in our mouths touching the Eucharist defied the prophecy His Body would not be touched by corruption. It is the same for receiving on the hand, Little boys receive and they are not a known quantity. They are not known to wash their hands at the appropriate times. Why all the rigamarole with priests washing their hands on the altar. We might with today’s habits just omit that part of the sacrifice too.We kneel in the presence of the Lord for Holy Communion as did the Jews when they saw Him or saw very definite signs of His Appearance, that is if we truly believe that under the the veil of bread and wine He is present. He is veiled because to see Him would cause us physical problems. The symbolism in the virtue of religion and the virtue of piety demands we symbolically say , “This is our God” Do you think the Host is still Christ if we make it obvious it is not worthy of respect, It is not my opinion or yours that count in the case of the Eucharist for the prophet Habakkuk tells us God cannot see those guilty of sinful disrespect. Remember that next time you receive.

Get thee to your nearest SSPX Chapel where all of these things still exist. We left the Crazy Novus Ordo in 1997 leaving Toledo, Ohio for Livonia Michigan. We have NEVER looked back. We shudder at he time we have to attend a “Mass” at the local parish no knowing what to expect. Half dressed women in short shorts & flip/flops, slovenly kids in jeans, dirty hands taking the host like it was no big thing. Is it any wonder the N.O. Church is dying, going backwards, just like Annibale Buginni designed it to happen. He was supposed to be a Freemason!! Last time I looked they HATE the Catholic Church. Looks to me they won in 1964.

Excellent advice Jim! That’s what I always recommend. God bless the SSPX.

“If you take away all the signs that express adoration, the attitude itself will disappear, and then the sense of the sacred,” said Dom Dysmas de Lassus, in The Power of Silence by Cardinal Sarah. It certainly has happened. Silence is another thing lost. The clergy will have a lot to answer for imho.

Very Blessed INDEED to say that all of the above losses are still very much the NORM in our parish … and its at a Novis O Mass

This is true for several parishes in our Archdiocese… but there may be some driving time needed to get out to the hinterland where these parishes and heroic Pastors reside and sacrifice for their Parish~!

IN our parish, where there is often STANDING ROOM ONLY, the Pastor hears Confessions before every Mass. NO EMHCs~ Only the Deacon and the priest~! also another LOSS not mentioned is the removal of the St Michael Prayer after Mass… this is the Norm here. there are NEVER and ANNOUNCEMENTS ANYWHERE during the Mass… never EVER~! the Priest leads the parish in , get this, NOVENAS and Devotional Seasonal / Liturgically Specific Prayers as the Calendar and Seasons change. there is OFTEN, Monthly and more, Benediction and Exposition immediately after Mass with these Prayers led by our Good Shepard. Except for visiting family such occasions of infant Baptisms … there is ever a Divine Silence throughout the church Before, During and AFTER MASS> Oh, Yeah.. there is always a Rosary Lead by parishioners prior to every Mass; and at the end of the dismissal HYMN, the priest exits directly into the SACRISTY… no mingling and joking around to disturb the MANY faithful remaining to have our HOLY COMMUNION With God ~Truly Present WITHIN US for about 15 mins after Receiving HIM.

BTW _ THE TRIDENTINE MASS IS FORBIDDEN ( by personal decree from Bishop to priest throughout nearly every parish in the diocese) TO BE OFFERED FOR ANY DESIGNATED / TYPICALLY SCHEDULED MASS ( Such as the usual 11am Sunday Mass) … BUT IT DOES GET OFFERED

WONDER of Wonders , MIRACLE of Miracles +++

Your “Bishop” sounds like a heretic, not a Catholic.

3, 4 and 7 are not gone from normal parishes. Most of these are cosmetic changes anyway.

I would ask the author and readers to give a list of 9 things the Holy Spirit have us with the Novus Ordo. If they cannot supply a list of 9 then they have not studied the liturgy or cannot see the work of the Holy Spirit through the Popes and Council Fathers.