A Daughter’s Love

On the morning of Whitsunday, the center aisle of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church (Rockdale, Illinois) overflowed with many confirmandi ready to receive the “Sacrament of the Seal.” Amongst the rows and columns of those in their Sunday best were three young sisters, the daughters of Miguel and Maricarmen Piña. The lively sisters’ Hispanic roots of dusky complexion and kind brown eyes brilliantly juxtaposed with their snowy white gowns and matching mantillas—garments emblematic of purity.

As the Bishop’s delegate stretched out his hands over the candidates, the priest dared to invoke the Third Person for His heavenly gifts: “Emitte in eos septiformem Spiritum tuum sanctum Paraclitum de caelis,” that is, “Send forth upon them from Heaven Your sevenfold gift Holy Spirit, the Paraclete.” Upon these sacred words, an outpouring of grace rushed in and swept through God’s house, and the splendor of sacramental ritual swelled and warmed these three little hearts.

One by one the sisters drew past the golden gates of the altar rail and knelt before the reverend father. A balsamic and camphorous aroma filled the sanctuary as the priest traced the sign of the cross with the sacred chrism on their foreheads. Immediately, the Holy Ghost infused Himself into their souls, and increased in them the strength and fortitude, as the Catechism of Trent states, to fight manfully and to resist their most wicked foes.[1] And, as a gentle reminder of the spiritual contest that lay before them, an ordinary handshake would not suffice. Thus, the priest gently struck each sister on the cheek, as if to say, “Be brave my little ones. May you valiantly endure to conquer all hardships, and suffer well for the sake of Jesus Christ.”

After the last Teum Deum was sung, and after the celebrant and his entourage retired into the sacristy, the three young sisters postured before the altar of Our Lady in order to commemorate the occasion. While the Blessed Mother smiled upon them from the heavens above, Maricarmen looked upon her girls with delight from the pews below. But in a moment of abundant jubilation and merriment, an admixture of sadness crept therein and remained. The hardship, the suffering, the difficulties of the spiritual contest would not come in some distant future but were already present in the here and now. For, the newly confirmed daughters stood in the very spot where only eight months prior their father lay in a casket enclosed by funeral torches and draped in a black liturgical pall.

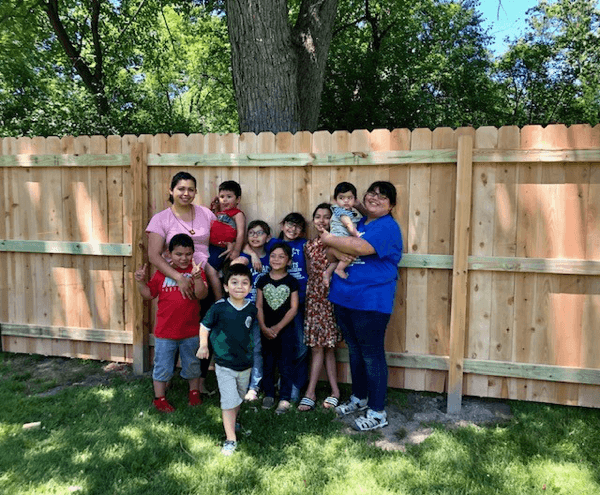

Now the daughters of Miguel [Gabriela, Sofia, and Daniela] cradled in their hands the candles symbolic of the divine spark enkindling their souls, while simultaneously clutching unto the golden frame which housed a portrait of Miguel—a testament to the inextinguishable flame of a daughter’s love for her departed father. For all those present, for all those who witnessed the little’s ones’ testimony, there was no eye unwatered, no stomach unturned, no heart unstrung with the memory of Miguel. He was thirty-six years old, and survived by his devoted wife Maricarmen and nine small children, one of whom was yet to be born.

A Return to the Father

Three days following Miguel’s departure from this physical domain, a Requiem Mass was offered on the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary, October 7th, for the repose of his soul. There, even the walls of the church seem to groan under the weight of sorrow as it bore down on the faithful present—heavy, deep, and acute. During the sermon, the priest’s voice gently cracked as he recalled the child Maricarmen carried within: “It is regrettable that Miguel will not, at least in this earthly life, meet his newest, youngest child… But that acquaintance will be made elsewhere, at another time, and in the best of circumstances.” With tear-stained eyes, the faithful staggered behind the coffin into the frigid air, as a trail of somberness followed each to their vehicles.

A long lachrymose line lingered behind the mourning-coach as it processed toward the sacred burial grounds for the Exsequiarum Ordo—the final act of the parish community caring for the body of its deceased and the marking of the separation of the mourners from their beloved. As Miguel’s coffin was lowered into the ground, and the earth blanketed his tomb, a profound hush flooded into the cemetery. It is in the silence that breeds the most rueful disquiet; for, the stillness of sound sways us towards the most penetrating awareness of our being: Mortality. “Dust thou art, and into dust thou shalt return.”[2]

However, in the silence, a whisper soothes and abates the pangs of despondency in the form of a still small voice, beseeching those that what was witnessed was not merely a body descending but a spirit rising. This still voice is the secret movement of the heart that only the deepest of lovers will recognize. And, if one can quiet themselves, if one can hush their interior for but a moment, they can verily hear the Lover’s whisper beckoning His beloved on home: “Fear not My gentle dove; I have summoned you by name, for you are Mine.”[3] In response, the beloved can only answer, “Your love has found me; I am yours.”

Man’s destiny does not reside amid the bronze effigies of angels or marble headstones, nor amongst the sandstone markers or the immortelle flower arrangements. No, Providence would have it that man’s portion goes beyond the grave, surpasses the firmament, and lives on in an everlasting and an ever-perfect transcendence: Beatitude. “Our citizenship,” marks the Holy Writ, “is in heaven.”[4] Perhaps, the atavistic and time-honored bishop of Caesarea, St. Basil the Great, best expresses the sentiments of those who journeyed with Miguel towards this eternal home:

We have not lost the lad; we have restored him to the Lender. His life is not destroyed; it is changed for the better. He whom we love is not hidden in the ground; he is received into heaven. Let us wait a little while, and we shall be once more with him. The time of our separation is not long, for in this life we are all like travelers on a journey, hastening on to the same shelter. While one has reached his rest another arrives, another hurries on, but one and the same end awaits them all.[5]

Neither lost nor hidden beneath some earthy surface, Miguel’s life is ameliorated and finalized with a return to the One who created him: “And the dust returns into its earth, from whence it was, and the spirit returns to God, who gave it.”[6] With the supernatural hope deep within our bosoms, there is the confidence that Miguel’s final end, his respite for a journey well-traveled, is an arrival at the fullness of glory and a return to the Father.

A Brother is Born

While one reaches rest, as St. Basil observes, another arrives. Six days after Miguel’s funeral rites were concluded and the faithful harrowed through their last valedictions, a new life arrived on the day of the Miracle of the Sun. On October 13th, Maricarmen gave birth to a son, Esteban Salvador Piña; and, for the three sisters, a brother was born.

While parturition brings forth new life, there is another kind of birth—metaphorical, ethereal, and charged with meaning—that begets a brother of a different sort. It is a nativity that emerges out of the depths of disarray and blooms at the heights of travail: “A friend is a friend at all times, and a brother is born for the time of adversity.”[7]

Never has prose or verse adequately captured the vastness of sorrow of a loved one lost. But a friend need only look into the eyes of the bereaved and see how they are drenched with pain to rightly attain its essence. A friend who loveth at all times cannot help but respond: “My friend’s misfortunes belong to me; my friend’s pains are indeed my own.” And, when one feels the wounds of the other, shares in their struggle, and strives to abate their sorrow, a brother or a sister is truly born.

A friend’s sympathy is a kind of salve for an aching heart. It is not a total panacea, but it may alleviate, in part, the sorrow. Accordingly, the sympathy of friends, as St. Thomas Aquinas reminds us, assuages pain and sorrow for two reasons. Firstly, sorrow has a depressing effect in which one tries to unburden themselves “so that when a man sees others saddened by his own sorrow, it seems as though others were bearing the burden with him, striving, as it were, to lessen its weight.”[8] Such a friend is, as it were, a Simon who shoulders the burden of another’s cross and labors onward toward Calvary. The second and “better reason” is because “when a man’s friends condole with him, he sees that he is loved by them.”[9] When a friend weeps with those that weep,[10] it is amongst the tears that the bereaved knows that they are loved. But the consolation of brotherly love is not limited to tears, and it may be expressed in a variety of ways: from Mass intentions to ardent prayers; tender words to mere presence; a comforting gaze to a warm embrace. Sometimes, however, this striving to lessen the sorrow, this display of consolation manifests itself in the building of a cedar fence.

Building Fences, Mending Hearts

The practicality of life does not relinquish its hold on man nor bend its neck to a time of mourning. For Maricarmen, the responsibilities of motherhood appear to be present everywhere and at the same time—whereas there is the teething of one child, there is the tantrum of another, all the while preparing the older adolescents to enter into a world that Our Lord says hates them.[11] Consequently, the rearing of children offers a fresh stripe of difficulty upon her back with the absence of Miguel, and the exhaustion of household management is further accompanied by the angst of accumulating finances.

While the day is fraught with fatigue, the evening’s amputation of nuptial conversation and affection threatens a near collapse. Lying upon the bed, the surviving spouse struggles to slow one’s breath, still one’s mind, and prepare for the quiet ache before the slumber. However, the still voice whispers a promise to the sorrowful that even in the fall they shall have their support to rise again: “If one fall, he shall be supported by the other.”[12] An army of the Triumphant stands ready to succor the downtrodden in her Lord, in her angels, and in her saints, while a band of brothers and sisters emerge from a small traditional Catholic parish to lighten the Piña family’s burden and, for the “better reason,” to ensure that they know they are loved.

In a display of fraternal love, a woman from St. Joseph communicates the family’s needs with the other parishioners, as if the very “heart of the church” was speaking to and animating the parts of the body: “I would like to let you know about a need close to us. It has been six months since Miguel has passed. Maricarmen and her nine children have carried this difficult cross as best they can.” The need is “close to us” because the loss of Miguel leaves a visible wound upon the entire parish. And just as a body seeks to mend itself when one of its parts is injured, so too does the traditional community seek to mend the ailments of her members. As the heart continues,

Our community’s prayers, material donations, and financial generosity, along with the gift of time helping Maricarmen with the children, meals, and various household duties have helped immensely to lighten their load, and they are so grateful for every prayer, donation, and kind deed. With that said, I wanted to make a big request. The Piñas live on an acre of land. Not being able to let her kids play outside without her constant supervision has become a source of stress for her, who understandably has more duties now that Miguel is gone. The solution to give her a break, some peace, and the ability to get some household things done while the kids safely play away from the busy road is to put a six-foot cedar fence around their property.

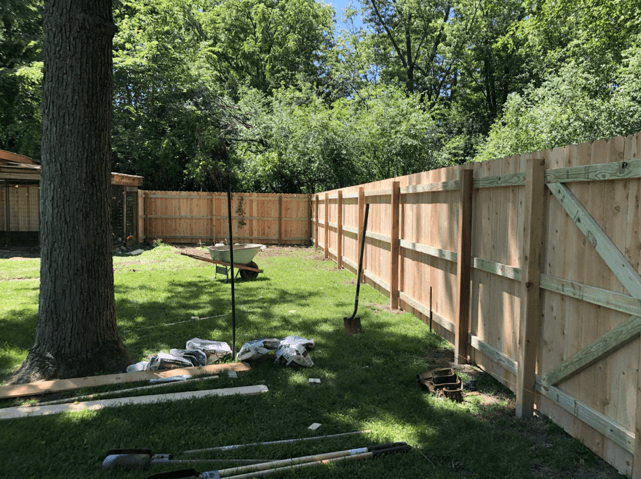

The heart’s plea quickly spread amongst the traditionalists. Many of the men with calloused hands and weathered boots offered their skills and labor without charge and without delay. Although the fence’s cost was significant due to sheer size of the yard and the soaring price of building materials, the necessary funds were not only met but were greatly surpassed with the excess rendered as a further donation.

Two days after the faithful of St. Joseph marched through the streets on Corpus Christi to honor their Eucharistic Lord, a few of the men, in a different type of procession, made their way to build a fence to honor their departed friend and aid of his family. Here, the physical manifestation of how the love of neighbor emanates from the love of God could not be mistaken. That is to say, the lex orandi informs the lex vivendi. And as the sun crested the horizon, pick-up trucks began to fill the Piñas’ front drive.

The workers warmly greeted one another with grins on their faces and the usual blue collared banter. There also to welcome them, albeit not as amiably, were numerous stacks of cedar pickets, piles of 2×4 stringers and 4×4 posts, and pallets of dry-set concrete. Looking over the large amounts of construction material, with a coffee in one hand and a cigarette in the other, the crew boss issued not so much of a request but more of an ultimatum: “The fence will be up by the day’s end.”

Rather than shrink from the demand, the men were determined to rise to the challenge and moved with a purpose. Right away, the boss measured and marked the fence line, while another group armed with a skid-steer loader and chainsaws laid waste to the overgrown vegetation that lay in the path. Then, as the laborers carried the lumber and concrete bags to the respected perimeter markings, two men began to drill into the hardened earth with a two-man gas-powered post hole digger.

Suddenly, the auger hit and imbedded itself into a sizeable tree root, which instantly stopped the dig. As a result, the abrupt halting motion caused the digger’s motor and metal handle bar to violently whip in the opposing direction and smash into the worker’s upper leg. Although the pain was noticeable, as he limped for a week thereafter, he continued to labor throughout the day. In his own words, “Whatever pain I had was not comparable to that of Mari and her children. So, I just kept working because I didn’t want to let them down.”

All the workers, in fact, carried within them the same sentiment. The sweat on their brows, the blisters on their hands, and soreness in their backs were all outward signs of the love they carried within for their friend Miguel. Their hands, backs, and legs would soon heal, but the building of the fence was an opportunity to begin to mend their hearts and become those brothers born for a time of adversity.

As the final post was set, the last of the concrete poured, and the sounds of pneumatic nail guns silenced, Maricarmen set out large containers with the most prized possession for a long day’s end—beer on ice. Now, with a cold brew in one hand and a cigarette in the another, the crew boss nodded his head as a sign of approval. For, the fence stood erect within a single day.

Although traditionalists are accused as ridged and denounced for having a dead faith, one need only to carry a single concrete bag for the Piña’s fence to realize just how tactless and unwarranted these accusations really are. Perhaps, one could merely catch a glimpse of this particular parish’s support for one another to recognize that the Body of Christ is one of friendship and brotherly love. Further, you could sit down with the newly founded widow, take her hands into yours, and sincerely listen. Maricarmen would tell you that traditional parishes like St. Joseph truly have each other’s best interests in mind, namely, they support each other towards the goal of reaching heaven. As a result, she states, “Being friends with people who have the same goals makes life more enjoyable, happier, and gives us the support we need in the ways we need it…We’re taken care of and not missing anything.”

For those who might oppose a traditional approach to the faith, even labeling it a ‘dead faith,’ the heart concludes: “I want to say one more thing. When you look around at the world and see how many things are spinning out of control, try to remember how the Body of Christ is still alive right in our midst. Rejoice and thank God for that!” Our Lord Jesus Christ is certainly alive and animating His Body to restore His Beautiful Bride unto Himself. Such a restoration of the Catholic Church happens in our own backyards, and sometimes, just sometimes, you have to put a cedar fence around it.

[1] Catechism of the Council of Trent, trans. John McHugh and Charles Callen (Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 1982), 223.

[2] Gen 3:19.

[3] “Fear not, for I have redeemed you; I have summoned you by name; you are mine” (Is 43:1).

[4] Phil 3:20.

[5] St. Basil of Caesarea, “Letter 5,” in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 8., trans. Blomfield Jackson, ed. Philip Schaff (Buffalo: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1895).

[6] Ecc 12:7.

[7] Prov 17:17.

[8] ST I-II, q. 38, a. 3.

[9] ST I-II, q. 38, a. 3.

[10] Rom 12:15.

[11] John 15:18; Matt 10:22.

[12] Ecc 4:10.