My apologies for a rather briefer offering for the 10th Sunday after Pentecost, although I have in my mind’s eye an image of you doing a fist pump while exclaiming, “yesssss”.

This is in part a gesture of self-defense. In the Epistle reading, Paul tackles for the Corinthians the issue of idolatry. Idolatry is contrary to the “Spirit of God”. It is a way of saying “Anathema… Accursed”.. to Jesus. Invoking Pachamama or the Grandmother of the West in order to enter the “circle of spirits”, comes to mind, which prods me rather to reflect more about the Gospel than the Epistle for the sake of both space and my blood pressure.

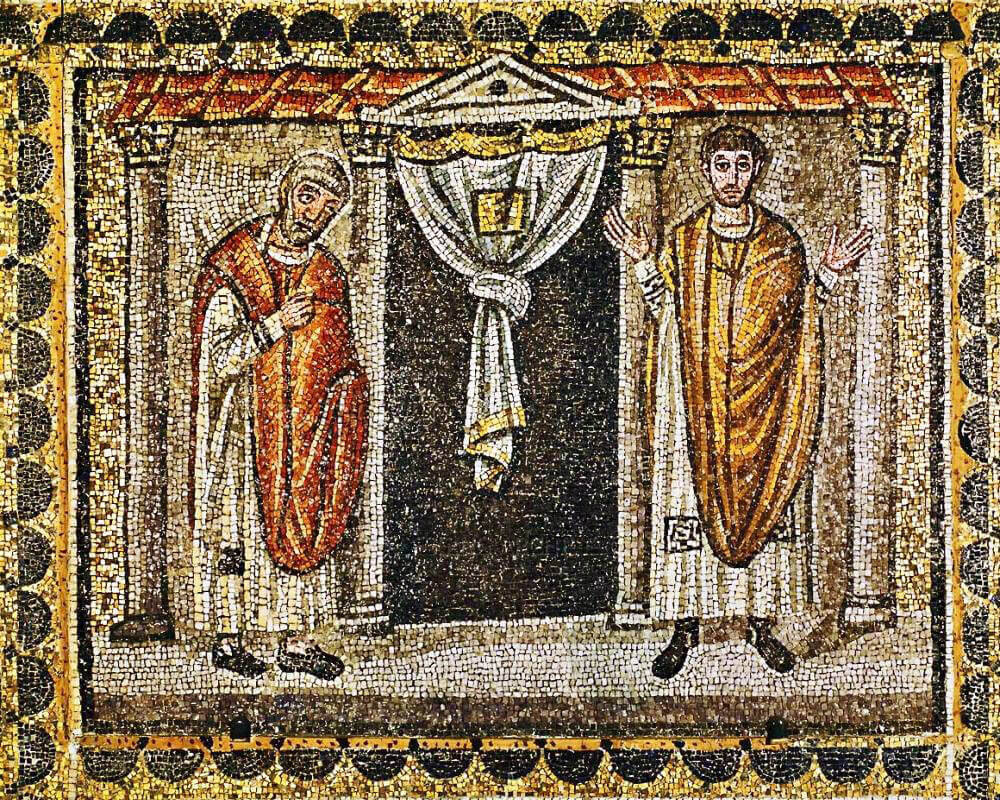

For our Gospel reading we have the Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, which is only in the Gospel of Luke.

Jesus told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and despised others: ‘Two men went up into the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector.’ (18:9-10)

Instantly our alert antennae ought to be waving, for as we hear those words sung or spoke, let us not forget that we are in the temple for Sunday worship. More on this in a moment.

Who is involved in this parable? You know well that in Christ’s day, tax collectors or “publicans” were collaborators with the occupying Romans. They kept a percentage of the taxes they collected, which could lead to abuse. Moreover, consorting with those Roman pagans, a Jew could be rendered ritually unclean.

The other figure Christ invokes is that of a Pharisee. Our view of Pharisees is more than likely skewed a little because the Lord is very hard on those who try to trick or trap Him in some point of Law. But remember that parables have as a regular feature a twist in the plot. In Christ’s day the Pharisees were, for the most part, highly respected, good, righteous men, trying to live their faith as best they could. The 1st century Jewish historian Josephus says that they were highly admired because of their zealous lives. So, the bad guy in the plot is, in the ears of Christ’s listeners, not the Pharisee (whom today we tend to look at dimly), but the tax collector (whom we might be inclined to give some leeway because of Matthew and Zacchaeus who climbs the sycamore in Luke 19).

In the parable, the Pharisee stands in the Temple to pray. That’s proper, of course, for the Jews prayed standing. He goes far forward in the Temple courtyard, which is implied by where the Publican stands (“far off”), probably just inside the gateway to the court. The Pharisee talks to God about the correct things that he has been doing according to the Law, such as fasting, tithing and avoiding the company of bad friends (“extortioners, unjust, adulterers”). We should all do those things, right? Didn’t the nuns back at St. Cunegonde Catholic Grade School admonish us to avoid the company of bad friends? Isn’t it a Commandment of the Church to give material support to the works of religion and maintain the Church’s temporal goods? Are we not required by tradition, law and commonsense to fast? Ought we not to pray in the assembly of the faithful with full, conscious and active participation, perhaps even far forward in church so that we can see what is going on?

All in all, it is hard to see what is wrong with the Pharisee, who is being what a Pharisee ought to be, righteous, obedient, zealous and, as the Hebrew means, “separated.” On the other hand, the Publican, perhaps ritually unclean and a seeming traitor to his people, is way in back, beating his breast and asking for mercy.

Two figures. Two attitudes of prayer.

It seems to me that we can find the catch in the parable in a simple phrase that isn’t instantly apparent in some English translations. The Pharisee, outwardly doing all the right things, is described by the Lord as praying, as the Greek text puts it, “pròs heautòn… with or toward himself,” In the Latin version, which I hope you hear sung, we have “apud se…”, the accusative case indicating this Pharisee as being interiorly focused on himself, not on God. The Publican, on the other hand, holds his heart up to God for mercy, even as he strikes his heart’s encasement.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church cites St. Augustine of Hippo (+430), and this parable’s conclusion about humility and exaltation, in its description of prayer:

2559 ‘Prayer is the raising of one’s mind and heart to God or the requesting of good things from God.’ But when we pray, do we speak from the height of our pride and will, or ‘out of the depths’ of a humble and contrite heart? He who humbles himself will be exalted; humility is the foundation of prayer, Only when we humbly acknowledge that ‘we do not know how to pray as we ought,’ are we ready to receive freely the gift of prayer. ‘Man is a beggar before God.’

So, you might be saying about this Pharisee that it would have been better for him not to have gone to the Temple at all, since he prayed in a self-referential way. Maybe it would have been better not to have prayed at all?

Doesn’t that sound a little like, “I know I committed a mortal sin, so maybe it would be better if I didn’t go to Mass on Sunday. After all, in the state of sin, nothing I can do is meritorious. And I don’t want people to see me not go forward for Communion.”

Let’s turn the sock inside out for a moment. There are different ways to sin. One of them is to sin by commission, doing something that one should not do. The other way is to neglect or omit to do that which one ought to do. That’s how we sin by omission.

If you neglect to pray, to fast, to do the things that we ought according to our state in life, we are as the Pharisee who is self-enclosed. It is a way of saying that you don’t need God. That’s what not praying is, too, not going to Mass, putting ourselves in near occasions of sin with people whose example can lead to sins.

As Holy Mass gets underway in the Vetus Ordo, even before the priest goes up to the altar, like going from the gateway to the front of the temple court, we all, especially in the person of the altar servers as our representatives in the sanctuary, bow and beat our breasts like the Publican in the parable. Holy Church knows all about human nature. She is the greatest expert on human nature there has ever been or ever will be. She knows through vast experience across cultures and centuries the common points we experience as images of God. And so we beat our breasts before the altar, joyfully confident as sinners begging for mercy: “ad Deum qui laetificat.”

We have to get our mind and heart right as we start our day, every day being another gift that the Lord does not owe us. We have to get our mind and heart right as we start Mass. The priest has his preparations, or should. How wise the Church has been in having him say prayers of intention and prayers as he vests. This ritual preparation helps him to break the bonds of worldly distractions. I beg you, dear readers, to leave Father alone before Mass! Give him some space. In the prayers at the foot of the altar and during his ascent to the altar as both priest and victim, referring to the entrance to the Holy of Holies, he whispers pleas for forgiveness of all of our sins, of everyone present:

Take away from us our iniquities, we beseech Thee, O Lord, that we may be worthy to enter with pure minds into the Holy of Holies, through Christ our Lord. Amen.

We beseech Thee, O Lord, by the merits of Thy Saints, whose relics are here, and of all the Saints, that Thou wouldst vouchsafe to forgive me all my sins. Amen.

The Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector is at play every time Father goes to the altar. It is at play every time you participate at Holy Mass. It is being lived out as we get out of bed in the morning and go to bed at night and attend to our vocation’s duties in the day: Who possesses the throne of my heart right now?

Why and for what am I doing what I am doing?

Circling back to the beginning of this reflection, I had brought up Paul on idolatry. We can see perhaps more clearly now how the attitude of the Pharisee in the parable is a kind of idolatry: his prayer is “toward himself.” What isn’t offered to God is offered to not-God.

My hope in these poor words and thoughts is that each day you may make a good examination of your heart and mind in making your choices about work and worship (which could ideally merge).

Allow me, in conclusion, to be provocative.

If you attend mainly the Vetus Ordo, the Traditional Latin Mass, … why? If you would attend the Vetus Ordo, but you are prohibited for whatever reason… why? I’ll ask the same question of those who would shun either the Vetus or the Novus Ordo. Why?

Jesus told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and despised others: ‘Two men went up into the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector.’ (18:9-10)