Is the recent “attack” on Vatican II a “crisis moment” for traditionalists? Are we turning on a legitimate and laudable Council instead of rightly directing our ire at the inept leadership that has followed it and betrayed it?

That has been the line of conservatives for a long time: a “hermeneutic of continuity” combined with strong criticism of episcopal and clerical brigandage. The implausibility of this approach is demonstrated by, among other signs, the infinitesimal success that conservatives have had in reversing the disastrous “reforms,” trends, habits, and institutions established in the wake of and in the name of the last council, with papal approbation or toleration. One is reminded of a secular parallel: the barren wasteland of American political “conservatism,” in which any remaining conformity of human laws and court decisions to the natural law is evaporating before our eyes.

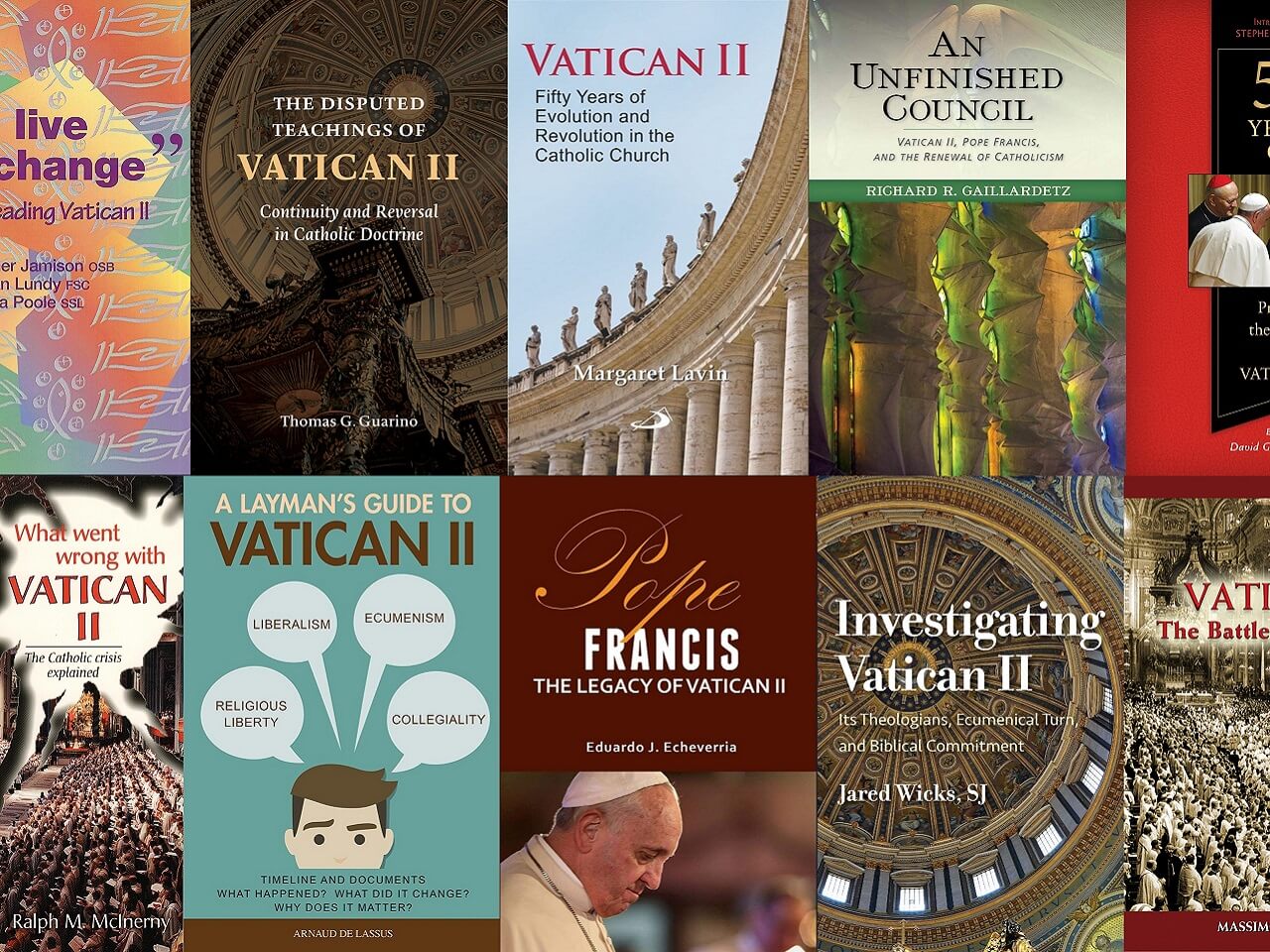

What Archbishop Viganò has recently been saying with a forthrightness unusual in today’s prelates (see here, here, and here) is but a new installment of a longstanding critique offered by traditional Catholics, from Michael Davies’s Pope John’s Council and Romano Amerio’s Iota Unum to Roberto de Mattei’s The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story and Henry Sire’s Phoenix from the Ashes. We have watched bishops, episcopal conferences, cardinals, and popes construct a “new paradigm,” piece by piece, for more than half a century — a “new” Catholic faith that at best only partially overlaps and at worst downright contradicts the traditional Catholic faith as we find it expressed in the Church Fathers and Doctors, the earlier councils, and hundreds of traditional catechisms, not to mention the old Latin liturgical rites that were suppressed and replaced with radically different ones.

So enormous a chasm gapes between old and new that we cannot refrain from asking about the role played by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council in the unfolding of a modernist story that has its beginning in the late 19th century and its denouement in the present. The line from Loisy, Tyrrell, and Hügel to Küng, Teilhard, and (young) Ratzinger to Kasper, Bergoglio, and Tagle is pretty straight when one starts connecting the dots. This is not to say there are not interesting and important differences among these men, but only that they share principles that would have been branded as dubious, dangerous, or heretical by any of the great confessors and theologians, from Augustine and Chrysostom to Aquinas and Bellarmine.

We have to abandon once and for all the naïveté of thinking that the only thing that matters about Vatican II are its promulgated texts. No. In this case, the progressives and the traditionalists rightly concur that the event matters as much as the texts (on this point, see the incomparable book by Roberto de Mattei). The vagueness of purpose for which the Council was convened; the manipulative way it was conducted; the consistently liberal way in which it was implemented, with barely a whimper from the world’s episcopacy — none of this is irrelevant to interpreting the meaning and significance of the Council texts, which themselves exhibit novel genres and dangerous ambiguities, not to mention passages that have all the traits of flat-out error, like the teaching on Muslims and Christians worshiping the same God, of which Bishop Athanasius Schneider gave a devastating critique in Christus Vincit [i].

It’s surprising that, at this late stage, there would still be defenders of the Council documents, when it is clear that they lent themselves exquisitely to the goal of a total modernization and secularization of the Church. Even if their content were unobjectionable, their verbosity, complexity, and mingling of obvious truths with head-scratching ideas furnished the perfect pretext for the revolution. This revolution is now melted into these texts, fused with them like metal pieces passed through a superheated oven.

Thus, the very act of quoting Vatican II has become a signal that one wishes to align with all that has been done by the popes — yes, by the popes! — in its name. At the forefront is the liturgical destruction, but examples could be multiplied ad nauseam: consider such dismal moments as the Assisi interreligious gatherings, the logic of which John Paul II defended exclusively in terms of a string of quotations from Vatican II. The pontificate of Francis has merely stepped on the accelerator.

Always it is Vatican II that is trotted out to explain or justify every deviation and departure from the historic dogmatic Faith. Is all this purely coincidental — a series of remarkably unfortunate interpretations and wayward judgments that an honest reading of the texts could dispel, like the sun blazing through the rainclouds?

Aren’t there good things in the documents?

I have studied and taught the documents of the Council, some of them numerous times. I know them very well. Since I am a “Great Books” devotee and have always taught for Great Books schools, my theology courses would typically begin with Scripture and the Fathers, then go into the scholastics (especially St. Thomas) and finish up with magisterial texts: papal encyclicals and conciliar documents.

I often felt a sinking of the heart when the course reached a Vatican II document, such as Lumen Gentium, Sacrosanctum Concilium, Dignitatis Humanae, Unitatis Redintegratio, Nostra Aetate, or Gaudium et Spes.

Of course — of course! — they have much that is beautiful and orthodox in them. They would never have gotten the requisite number of votes had they been flagrantly opposed to Catholic teaching.

However, they are also sprawling, unwieldy, inconsistent committee products, which needlessly complicate many subjects and lack the crystalline clarity that a council is supposed to work hard to achieve. All you have to do is look at the documents of Trent or the first seven ecumenical councils to see brilliant examples of this tightly constructed style, which cut off heresy at every possible point, to the extent the council fathers were capable of at that particular juncture [ii]. And then there are the sentences in Vatican II — not a few of them — at which ones stops and says: “Really? Am I really seeing these words on the page in front of me? What a [messy; problematic; proximate-to-error; erroneous] thing to say” [iii].

I used to hold, with conservatives, that we should “take what’s good in the Council and leave behind the rest.” The problem with this approach is captured by Pope Leo XIII in his Encyclical Satis Cognitum:

The Arians, the Montanists, the Novatians, the Quartodecimans, the Eutychians, certainly did not reject all Catholic doctrine: they abandoned only a certain portion of it. Still who does not know that they were declared heretics and banished from the bosom of the Church? In like manner were condemned all authors of heretical tenets who followed them in subsequent ages. “There can be nothing more dangerous than those heretics who admit nearly the whole cycle of doctrine, and yet by one word, as with a drop of poison, infect the real and simple faith taught by our Lord and handed down by Apostolic tradition” (Anon., Tract. de Fide Orthodoxa contra Arianos).

In other words: it is the mixture, the jumble, of great, good, indifferent, bad, generic, ambiguous, problematic, erroneous, all of it at enormous length, that makes Vatican II uniquely deserving of repudiation [iv].

Weren’t there always problems after Church Councils?

Yes, without a doubt: Church councils have been followed by a greater or lesser degree of controversy. But these difficulties were usually in spite of, not because of the nature and content of the documents. St. Athanasius could appeal again and again to Nicaea, as to a battle ensign, because its teaching was succinct and rock-solid. The popes after the Council of Trent could appeal again and again to its canons and decrees because the teaching was succinct and rock-solid. While Trent produced a large number of documents over the course of the years in which the sessions took place (1545–1563), each document is a marvel of clarity, with not a wasted word.

At very least, the Vatican II documents failed miserably in the Council’s purpose as explained by Pope John XXIII. He said in 1962 that he wanted a more accessible presentation of the Faith for Modern Man.™ By 1965, it had become painfully obvious that the sixteen documents would never be something you would just gather into a book and hand out to every layman or inquirer. One might say the Council fell between two stools: it produced neither an accessible point of entry for the modern world nor a succinct “plan of engagement” for pastors and theologians to rely upon. What did it accomplish? A huge amount of paperwork, a lot of windy prose, and a winky nudge: “Adapt to the modern world, boys!” (Or, if you don’t, get in trouble with — to borrow a phrase from Hobbes — “the irresistible power of the mortal god” in Rome, as Archbishop Lefebvre quickly discovered.)

This is why the last council is absolutely irrecoverable. If the project of modernization has resulted in a massive loss of Catholic identity, even of basic doctrinal competence and morals, the way forward is to pay one’s last respects to the great symbol of that project and see it buried. As Martin Mosebach says, true “reform” always means a return to form — that is, a return to stricter discipline, clearer doctrine, fuller worship. It does not and cannot mean the opposite.

Is there anything of the substance of the Faith, or anything of indisputable benefit, that we would lose were we to bid the last council goodbye and never hear its name mentioned again? The Catholic Tradition already has within itself immense (and, especially today, largely untapped) resources for dealing with every vexing question we face in today’s world. Now, almost a quarter of the way into a different century, we are at a very different place, and the tools we need are not those of the 1960s.

What, then, can be done in the future?

Ever since Archbishop Viganò’s June 9 letter and his subsequent writing on the subject, people have been discussing what it might mean to “annul” the Second Vatican Council.

I see three theoretical possibilities for a future pope.

- He could publish a new Syllabus of Errors (as Bishop Schneider proposed all the way back in 2010) that identifies and condemns common errors associated with Vatican II while not attributing them explicitly to Vatican II: “If anyone says XYZ, let him be anathema.” This would leave open the degree to which the Council documents actually contain the errors; it would, however, close the door to many popular “readings” of the Council.

- He could declare that, in looking back over the past half-century, we can see that the Council documents, on account of their ambiguities and difficulties, have caused more harm than good in the life of the Church and should, in the future, no longer be referenced as authoritative in theological discussion. The Council should be treated as a historic event whose relevance has passed. Again, this stance would not need to assert that the documents are in error; it would be an acknowledgement that the Council has shown itself to be “more trouble than it’s worth.”

- He could specifically “disown” or set aside certain documents or parts of documents, even as parts of the Council of Constance were never recognized or were repudiated.

The second and third possibilities stem from a recognition that the Council took the form, unique among all ecumencial councils in the history of the Church, of being “pastoral” in purpose and nature, according to both John XXIII and Paul VI; this would make its setting aside relatively easy. To the objection that it still, perforce, concerns matters of faith and morals, I would reply that the bishops never defined anything and never anathematized anything. Even the “dogmatic constitutions” establish no dogma. It is a curiously expository and catechetical council, which settles almost nothing and unsettles a great deal.

Whenever and however a future pope or council deals with this thoroughly entrenched mess, our task as Catholics remains what it has always been: to hold fast to the Faith of our fathers in its normative, trustworthy expressions, namely, the lex orandi of the traditional liturgical rites of East and West, the lex credendi of the approved Creeds and the consistent witness of the universal ordinary Magisterium, and the lex vivendi shown to us by the saints canonized over the centuries, before the era of confusion set in. This is enough, and more than enough.

[ii] It is noteworthy that John XXIII had appointed preparatory commissions that produced short, tight, clear documents for the upcoming council to work with — and then allowed the liberal or “Rhine” faction of council fathers to chuck out these drafts and replace them with new ones. The only exception was Sacrosanctum Concilium, Bugnini’s project, which sailed through without much trouble.

[iii] It’s not just a matter of poor translations; the very first translations were generally good, and then later translations dumbed the texts down.

[iv] As Cardinal Walter Kasper admitted in an article published in L’Osservatore Romano on April 12, 2013: “In many places, [the Council Fathers] had to find compromise formulas, in which, often, the positions of the majority are located immediately next to those of the minority, designed to delimit them. Thus, the conciliar texts themselves have a huge potential for conflict, opening the door to a selective reception in either direction.”