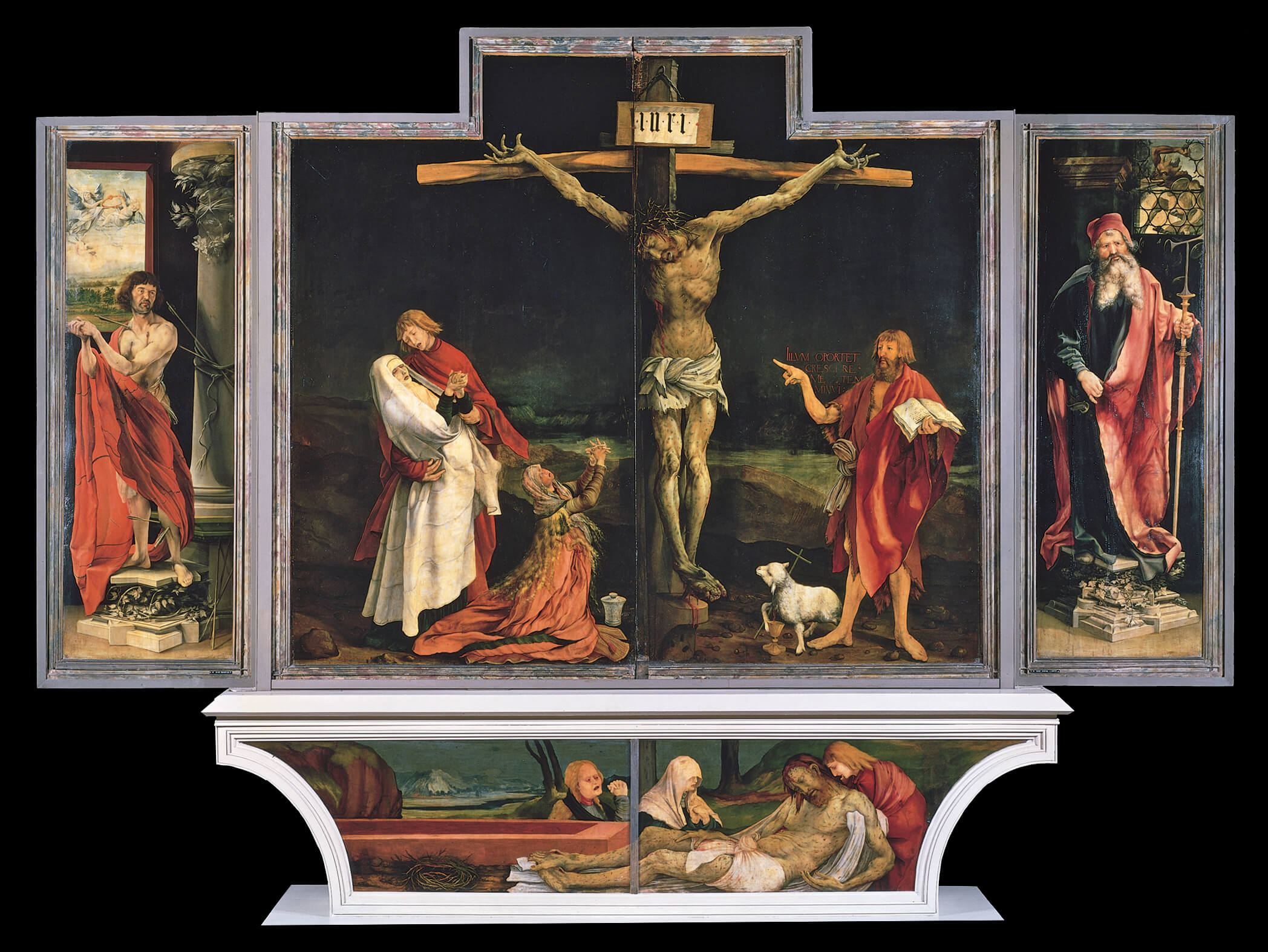

Above: the famous Isenheim Altarpiece.

As we approach Holy Week, many faithful look for aids to meditation on the passion of Christ. Some watch Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ, while others pray their favorite stations of the cross. However, perhaps another way to ponder the events of the Passion is to turn to the music which this season has inspired the greatest composers of Christendom to write: Bach’s St Matthew Passion, Buxtehude’s Membra Jesu Nostri, or Victoria’s Lamentations. For those who have difficulty meditating on Scripture, or who wish to enrich their lives with musical beauty, such a Lenten listening project can be an opportunity to approach God through the immense uplifting power of sacred art. Today I would like to draw attention to a lesser known work in this genre: the cycle of Tenebrae Responsories by the Italian nobleman Carlo Gesualdo.

Much ink has been spilled over Carlo Gesualdo’s turbulent life. A few years before he was born in 1566, Carlo’s family had acquired the principality of Venosa in Southern Italy. Carlo was named after his uncle, a Carlo whom posterity knows as Saint Charles Borromeo. His mother was the niece of Pope Pius IV. From an early age Carlo showed little interest in anything but music; he played the lute, baroque guitar, and harpsichord.

After his older brother died young, Carlo became the heir-apparent to the Principality of Venosa, abandoning the prospect of an ecclesiastical career. He would succeed his father as Prince in 1591. In the meantime however, he married his first cousin, Donna Maria d’Avalos, in 1586. Donna Maria had already been widowed twice before the age of thirty, having first married at 15. Within four years of her marriage to Gesualdo, however, Maria was enmeshed in an affair with Fabrizio Carafa, Duke of Andria. Some speculate that this was due to Gesualdo losing interest in her. However, on October 16th, 1590, Gesualdo discovered Maria and Fabrizio in flagrante, and killed them both on the spot. According to the law of the time, Gesualdo was not charged with homicide by the legal inquiry that followed because of the couple’s adulterous behavior. Nonetheless, Gesualdo’s mind began to deteriorate.

Gesualdo continued to compose music and associate with leading musicians. Four years after the unhappy ending to his first marriage, he married Eleonora d’Este. Although Elenora was more virtuous than Maria, this too would prove an unhappy marriage, and she tried to obtain a divorce. Perhaps Gesualdo’s own faithfulness in marriage was not dissimilar to that of his first wife. Gesualdo unsurprisingly suffered from extreme depression, and began to seek spiritual healing. Between having himself beaten by his servants and seeking relics of his uncle St. Charles Borromeo, it is not clear that his mental illness was helped all that much. He also composed religious music, like the Tenebrae Responsories published in 1611, to which I will turn in a moment. Gesualdo died in isolation at his castle in Avellino.

Despite his troubled life, Gesualdo’s depth of feeling resulted in breathtaking music. As a nobleman, he was his own patron and could therefore compose as wildly as he liked without the concern of having to please a royal supporter. Gesualdo’s music is highly chromatic and is among the most difficult vocal music ever composed before the atonal period. I remember one singer telling me that a choir like the Choir of King’s Cambridge could sight-read anything but Gesualdo. Because of his avant-garde aesthetic and lurid personal life, Gesualdo has attracted much attention in music circles and served as inspiration for troubled and rebellious artists ranging from Stravinsky to Aldous Huxley to modern rock guitarist Anna Calvi. Putting the framing of Gesualdo as a herald of the “modern artist” aside, however, let us take a look at his Tenebrae Responsories.

Composed late in his life as he searched for resolution to his disintegrating life, Gesualdo’s Responsories are composed for six voices. They set the texts from the traditional Roman Rite Tenebrae office of Matins for Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. Here I will link to some excellent performances of them, while providing a few words of commentary to point out Gesualdo’s compositional effects.

Gesualdo often pushes the normal vocal ranges, frequently starting a phrase with a chord voiced in the lower four voices, and then repeating it with the addition of the higher parts.

The first piece in this performance, and the responsory for Tenebrae itself, In Monte Oliveti, is the prayer of Jesus to the Father: “If it be possible, let this chalice pass. The spirit is strong, the flesh weak.”

The tormented vocal lines are constantly crossing each other, and here are tastefully ornamented. In this music we see extreme emotionalism expressing itself in a style which is compatible with liturgical worship, taking the ancient Biblical texts and fitting them to music which stretches the limits of traditional western tonalism. As such, they are an opportunity to consider how Christ’s passion was both a fitting way of saving mankind and a horrific paradox.

In Caligaverunt oculi mei, line after line of flowing dissonance cascades over the words dolor meus—my sorrow.

Clashing and strange motifs combine with Renaissance idioms to produce a feeling of disorientation in a familiar place. On qui consolabatur me (“he that comforted me”) the voices come together in homophony full of sweet consonances. The voices are widely spaced, producing unusually rich chords. Try meditating on the translation while following the musical setting of each phrase:

My eyes are darkened by my tears:

For he is far from me that comforted me:

See, O all ye people,

if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.

O all ye that pass by, behold and see

if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.

Tristis Est Anima Mea (here sung by an ensemble named after Gesualdo) is filled with word painting, where the composer tries to make the music sound like what the text represents.

Thus, on “and you shall flee,” the different parts all have rapidly descending scales, as if scrambling into hiding. With the words “and I will go to be sacrificed for you,” the harmonies take a surprising and disturbing turn modally, with consecutive half steps that don’t fit into the key; C and F sharps and naturals follow immediately upon each other, creating a velvety anguish. At the verse, the voices are reduced to four, singing the text in homophonic chords (that is, the voices move with each other) filled with chromatics. Plange Quasi Virgo is set in a similar manner, and presents this text:

Weep like a virgin, my people,

howl, keepers of the flock, covered with ashes and wearing hair-shirts,

for the great and very bitter day of the Lord will come.

Prepare yourselves, priests, and lament, acolytes before the altar,

cover yourselves with ashes.

For the great and very bitter day of the Lord will come.

One of my favorites is O Vos Omnes.

Again, it begins with a low chord which the higher voices join on its repetition. The initial text is set in powerful chords, the voices moving simultaneously. Daring suspensions and modulations mark the words “if any sorrow be like mine” before cadencing eerily.

Like Allegri, Gesualdo also set the Miserere with its traditional use in the office of Tenebrae in mind.

Rich and brooding, Gesualdo’s setting is filled with anguish rather than the lyric transcendence that Allegri’s descant gives the piece (or, at least, the descant with which we have all become familiar, though it is not from Allegri).

If you want to take some time this Lent to familiarize yourself with Gesualdo’s Tenebrae music, the albums I would recommend as the best performances are Gesualdo: Responsoria 1611 (Collegium Vocale Gent, dir. Philippe Herrewege); the Tenebrae Choir (dir. Nigel Short) recording Gesualdo/Victoria-Responsories and Lamentations For Holy Saturday; and finally the album Gesualdo Tenebrae by Graindelavoix (dir. Björn Schmelzer). All are available on services like Spotify and Amazon Music.

Perhaps inviting friends or family for an hour of Gesualdo one Sunday evening could be an opportunity to share reactions and insights to the music and the texts. The texts may be found in a hand missal or the recording’s liner notes or online. If you are a musician, you might try following the scores as you listen (available on CPDL); or find some religious artwork to look at while you listen, like that of Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, or James Tissot’s life of Christ painting cycle. As many seek to enrich their Lent and also desire to become more familiar with the great art Catholicism has inspired, such a listening session could be an opportunity to nourish both. Say a prayer for Gesualdo’s soul, and thank God that he was able to contribute some beauty to the world despite his sins and struggles. The sweet sorrow of his responsories should give us hope that we too, despite our failings, can offer God something worthwhile with this Lent—which may well include turning a receptive ear to what Gesualdo tried to offer God through his music.

NOTE: readers may be interested in listening to a responsory I composed a few years ago in the style of Gesualdo: