The Knights of Malta are a nine-hundred-year-old order of the Catholic Church, and one could aptly write a treatise on why tradition is and should be cherished among them — but that is not what I am concerned with here. The purpose of this article is to rebut the wholly fantastic account of the Order’s recent vicissitudes peddled by commentators such as Christopher Lamb and Austen Ivereigh by occasion of the Order’s recent decision to forbid the use of the traditional Mass in official ceremonies. The Tablet for 12 June 2019 published Lamb’s article, “Order of Malta head bans Old Rite,” whose misstatements need to be corrected in two main areas.

The first is the myth that Fra’ Matthew Festing, grand master until he was forced out in 2017, was in any way leading an anti-papal movement. This is implied by Lamb’s statement that “The Grand Master’s latest pronouncement [banning the old rite] is ruling out, in stark terms, the idea that the order can become a traditionalist bastion in opposition to this pontificate.” Austen Ivereigh calls it a “[s]trong move designed to ensure that Knights will not again be used as [a] fifth column for anti-papal, anti-Vatican II traditionalists.”

This is a complete distortion of recent events in the Order. Fra’ Matthew Festing, who was elected grand master in 2009, was certainly a traditionalist, and his election was accompanied by the accession of other traditionalists to positions in the government in the Order, but nobody had the remotest idea that this was an anti-papal move. It was fully in harmony with the direction of Benedict XVI’s papacy, and when Pope Francis was elected, nobody thought the situation had changed. In his first three years, Francis did not yet seem the overt enemy of tradition that he has since shown himself to be. Indeed, his appointment of Cardinal Burke as patronus of the Order of Malta in 2015 looked like a blessing to the traditionalist movement within the Order. (That indeed is why Baron Boeselager, the grand chancellor, opposed it from the start: behind the grand master’s back, he made several personal visits to the Vatican to try to stop the appointment, and even to reverse it after it was made. This action alone would amply justify the grand master’s wish to dismiss him). Grand Master Festing met Pope Francis on many occasions, got on well with him, and expressed admiration for him in various respects. Up to the end of 2016, no one had the slightest notion of any opposition between the Order of Malta and Pope Francis.

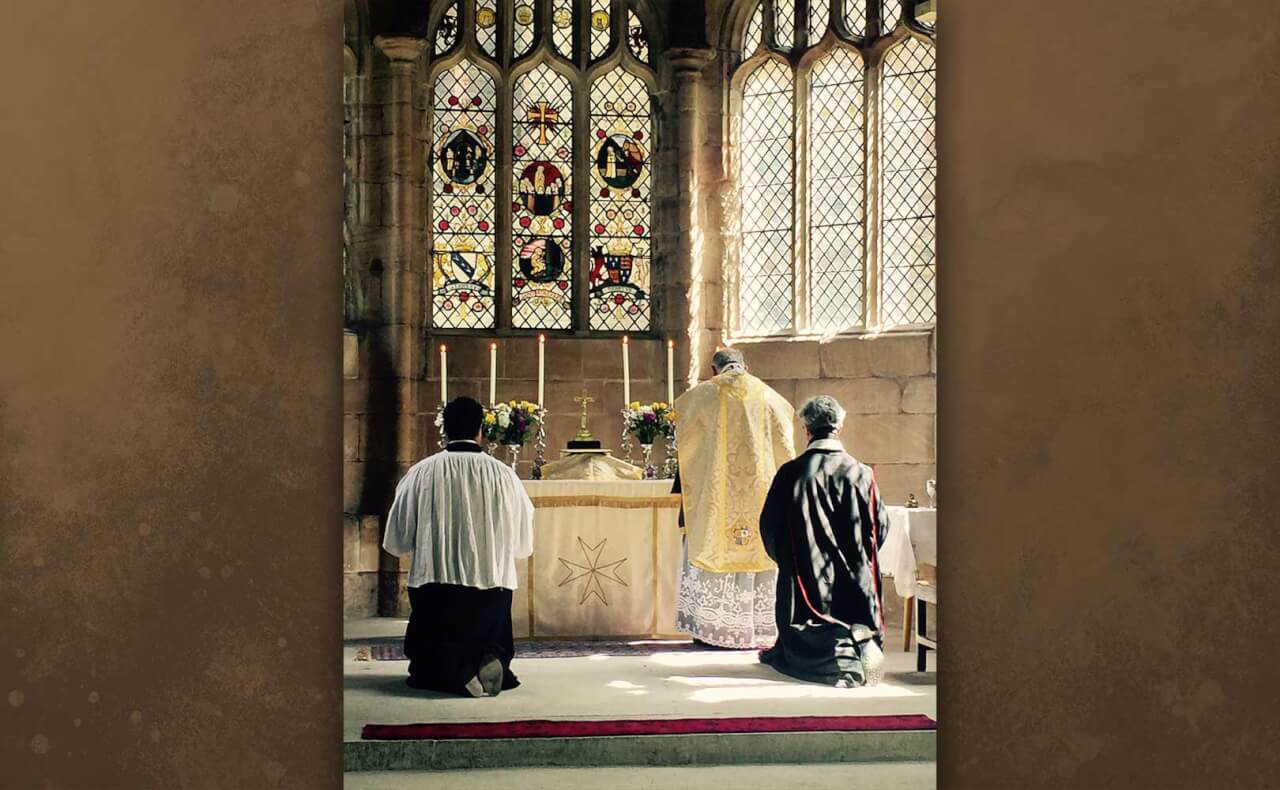

It is also completely false to say, as Lamb does quoting an unnamed source within the Order, that Fra’ Matthew’s aim was to “make the Tridentine rite, and traditionalism the central ideology of the order” or that traditionalism became part of the “sell” in attracting professed knights. Fra’ Matthew never attempted to impose the old rite on anybody; even the Mass in his own magistral chapel in Rome, which he attended every day, continued to be said in the new rite. Only in a couple of countries, by initiative of the local members themselves, were some Order ceremonies held in the old rite. Nor was there any traditionalist “sell” to attract Knights of Justice. Fra’ Matthew indeed recruited many more professed, but the vast majority entered without the slightest notion that there was any penchant for liturgical traditionalism in the Order. The same remark applies to Fra’ Duncan Gallie, who was in charge of vocations; he was himself a traditionalist, but he welcomed applicants from wherever they came. Only in the Grand Priory of England has there been a concentration of traditionalists among the professed — a phenomenon of long standing, owing nothing to Fra’ Matthew’s policies.

Irrespective of the liturgical aspect, it is also totally false to speak, as Lamb does, of the “public battle with Pope Francis at the end of 2016, and early 2017” or to say, “It was Festing, egged on by Cardinal Burke, who took on the Pope during the 2016/17 saga.” It is indeed almost the opposite of the truth. The dismissal of Baron Boeselager as grand chancellor, which sparked the crisis in December 2016, was undertaken in response to a letter of Pope Francis to Cardinal Burke on 1 December, in which he expressed displeasure at the distribution of condoms in the Order’s charitable works and called for action to prevent it. (I am not arguing that Pope Francis asked for Boeselager’s dismissal: he did not. But he was the official in charge during the time concerned, and in Fra’ Matthew’s view, there was such a thing as ministerial responsibility). Fra’ Matthew thus dismissed the grand chancellor and was taken by surprise by the intervention, not of Pope Francis, but of Cardinal Parolin, who in a letter a few days later demanded Boeselager’s reinstatement. It is well known that the reason for this intervention had to do not with condom distribution, but with the concerns of a Swiss fund under which both the Order of Malta and various Vatican figures stood to receive large sums of money; the dismissal of Boeselager threatened the success of his negotiations.

At first, the grand master, and his subordinates in the Order’s government, thought there was merely a clash between Cardinal Parolin and Cardinal Burke. Relying on the letter of 1 December, they thought Pope Francis was on their side. The supposed defiance of the Order in the weeks of December and January was not against the pope, but against what appeared a completely uncalled-for intervention by the secretary of state. The moment Fra’ Matthew realized that Parolin had Francis behind him, he caved in, and indeed his prompt resignation when Francis demanded it on 24 January is proof of it. The pope asked for the resignation (a wholly disproportionate retaliation for what had happened) because he knew in advance that Fra’ Matthew would give it. But all this was purely related to the dismissal of Boeselager. There was no question of the Order being seen as a center of traditionalist opposition to the pope; that is just a myth that commentators like Lamb and Ivereigh concocted afterward.

It follows that the recent letter by the Grand Master forbidding the old rite has nothing to do with a supposed attempt under the former regime to entrench traditionalism in the Order. The first thing to be said about the letter is that its real author is not the Grand Master but the Grand Chancellor, Boeselager, who is thus celebrating his having been re-elected for another five years at the Chapter General last May. It is part of Boeselager’s spiteful vendetta against the grand master whom he ousted two years ago. The grand master, Fra’ Giacomo dalla Torre, is a nonentity whom even the Italian knights were not prepared to back against Festing in the magistral election of 2009, and he became Boeselager’s candidate for grand master last year for precisely that reason. He could be trusted to be the grand chancellor’s unqualified puppet, and he has fully lived up to that expectation.

Yet there is an explanation that goes deeper than mere revenge: the banning of the traditional rite is part of Boeselager’s instinctive totalitarianism, which has become obvious to all in the last two years. Since being reinstated by Pope Francis, he has worked to stamp out every vestige of the previous regime, and in the Chapter General elections of last May, he almost completely succeeded. The banning of the old rite is of a piece with that. In contrast to the traditionalist Festing, who did not impose his preference on anyone, the “liberal” Boeselager tolerates no dissent, even from traditionalists in a few countries who wish to use the old rite.

These tendencies have an implication for the changes that Boeselager is seeking in the very nature of the Order of Malta, and it relates to Christopher Lamb’s assertion that the banning of the old rite is part of a “reform.” In this, Lamb repeats the radical distortion that he has repeatedly been advancing against the Knights of Justice, those who take the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience and constitute the religious core of the Order of Malta. Lamb alleges, “The Holy See has serious concerns about the formation and the quality of their religious life,” and that their observance has become “alarmingly lax” in recent years. This is the opposite of the truth. The observance of religious duties by the professed has been tightened up notably, and precisely by the new rules introduced by Fra’ Matthew Festing after he became grand master in 2009. He was also working on an improved program of formation, a plan that has been struck a grave blow by his dismissal.

The present regime (and Lamb echoes their line) are talking as if the Knights of Justice were disgracing their religious profession by ignoring their obligation to live in community, but this is a view based on ignorance of the Order’s nature. A military order is not monastic, and its members have never been obliged to community life. In the heyday of the Order, knights served as soldiers, royal ministers, and diplomats, as became their station, and a knight was expected to close his career as administrator of one of the commanderies or priories (the European estates from which the Order drew its wealth), not living in community. The present idea of reform is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of a military order and an assumption that a religious vocation can only be monastic in type. It is an ignorant proposal, overlooking the lesson of other hospitaller orders today (for example, that of St. John of God) and even that of institutes such as Opus Dei, which show the direction of an active religious vocation in the modern world.

Now, I am the first to admit that the vocation of the Knights of Justice has suffered in modern times — but the problem arose two centuries ago, from the loss of the military role that the Order had in Malta and the confiscation of its European properties. This left it unable to support its professed members or to give them a corporate role (except the few who served in the Order’s government), with the result that they were obliged to depend on private means or work for a living. The incongruity was not so obvious when Knights of Justice were aristocrats, following a vocation that was traditional in their families, but it has become obtrusive in the last thirty years, when the class was opened up to non-nobles, who thus give the appearance of assorted lawyers, bankers, schoolmasters, etc. who just happen to have taken religious vows. But this defect is not the result of religious laxity; on the contrary, it was created by the too conscientious belief that the Order’s funds ought to be devoted exclusively to hospitaller work. The Order of Malta has had large resources at its disposal, from the donations of its supporters, and it would have been possible to create endowments to support the Knights of Justice and employ them in active hospitaller work. But it has always shrunk from diverting sums to such a purpose, with the result of the unsatisfactory situation we have today. The professed knights themselves are in no way to blame for it.

One particular aspect of this should be pointed out: until 1929, all the members of the Order’s government were professed knights, as was proper to a religious order. After that date, one exception was permitted, in the person of the grand chancellor, owing to the increasingly onerous responsibilities of that office. When the Order introduced a new constitution, at the behest of the Vatican, in 1961, the government was expanded, and a new requirement came in. It was envisaged that all the ten members of the Sovereign Council, besides the grand master, should normally be professed, but the constitution permitted up to five members to be Knights of Obedience, who made religious promises instead of vows. Unfortunately, the secularist spirit of the time led to this loophole being abused. What was intended as an exception was treated as the norm. It became the practice that the maximum of five Knights of Obedience were invariably elected to the Sovereign Council instead of professed. This is the true religious abuse in the Order that ought to be reformed, but Boeselager’s intention is exactly the opposite. He wants to entrench the abuse and take it farther, excluding the professed almost entirely from the Order’s government.

Of course, such objectives are the natural consequence of one’s idea of what the Order should be, and Boeselager has made his own view obvious throughout his career. During his twenty-five years as hospitaller and his five years as grand chancellor, he has consistently opposed anything that savored of the Order’s historic identity — i.e., any sort of military association and any involvement in the Holy Land, where the Order had its origin. Throughout that time, while the plight of Christians in the Middle East has become desperate, and cried out so much for the aid of a powerful Western agency, Boeselager has resolutely turned his back on any involvement in that area. The only work of the Order in the Holy Land is a maternity hospital in Bethlehem founded before Boeselager became hospitaller.

Such attitudes have their consequence in how one views the religious element. If one’s ideal for the Order’s charitable works is that it should be distributing condoms all over the world, one obviously does not think of a cadre of professed religious to carry out such a policy. The only role Boeselager can see for the Knights of Justice is as a useless monastic appendage, when in fact they should be active men, as they were in the Middle Ages, carrying out a vocation in the world where it is most needed. Boeselager is in every sense an anti-traditionalist: he is hell-bent on turning the Order of Malta into the opposite of what its origins and tradition have made it.