Above: Hiroshima aftermath.

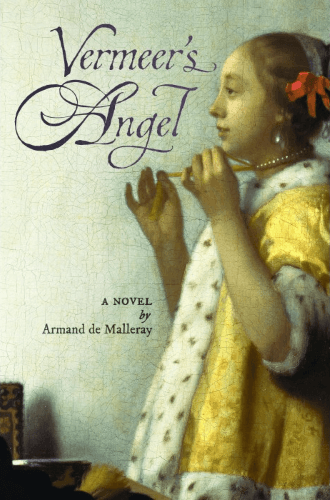

Vermeer’s Angel is no ordinary novel. In the process of a brilliant interweaving two separate but closely linked narratives, it explores many separate themes, and unlike most modern novels, leaves the reader with much to think about. Despite spies, evil adversaries and Vatican plottings, it is an antidote to the many Dan Brown look-alikes: this is essentially a truly Catholic novel. It is a gripping spy story with a contemporary relevance although set in the relatively recent past. While the story offers insights into the workings of the Vatican, particularly with regard to its ongoing Ostpolitik strategies, it also defines a process of conversion in the hidden workings of the human soul: a meditation on a spiritual coming of age with all its culpabilities.

The Prologue, introducing two key characters Bishop Dorf and Monsignor Altemps – both closely in touch with the Vatican but for different reasons – sets out a scheme of diverging clerical ambitions and machinations which hold the attention right to the dramatic end of the narrative. The outgoing, likeable Dorf subsequently offers amusing perspectives on a clerical love of luxury that dates back to Chaucer, but the ambition to see a lifetime’s efforts rewarded by a cardinal’s hat is his motivation. In contrast, the terminally ill Altemps apparently longs for the seclusion and secrecy of a cloister in which to die, while his old friend is desperate to persuade him to fall in with his plans for the cardinalate. As their story develops it becomes evident that nothing is quite as it seems. Dorf’s unexpected connection with an unidentified Communist spy calls into question his eligibility as cardinal, and the search for this spy’s identity is the plot which holds the entire novel together.

Interleaved with Dorf’s story is the closely linked memoir of enigmatic Japanese art critic Ken Kokura. In the gripping opening to Part One of the novel, Kokura suffers a total memory loss in the trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, clearly based on contemporary accounts of the disaster and echoing the miraculous survival of Jesuits in the target zone of the first bomb. Kokura’s search for his identity – indeed for his soul – runs concurrently with his role as a spy; in the process of rehabilitation, he is apparently recruited by a Moscow agent and agrees to pass on information in exchange for an education, which leads to a career in the authentication of paintings. Despite, or perhaps because of, his gradual recovery of memory, he proves an unreliable narrator, and it is for the reader to try to unravel his true role.

This is a novel with a wide perspective, covering a period of five decades or so, with scenes set in Europe, Japan, China, and America. The observation of differences in lifestyle, values, modes of expression is acute and illuminating, and the prose style reflects these, contrasting for example Kokura’s careful narrative with the clichéd business-speak of advertisers who are without conscience. There is humour in the depiction of some of the clerics, but as the title hints, this is a serious book about the role of art in the spiritual life of man. The works of art closely observed and knowledgably analysed in their relevance to the plot include a selection of well-known paintings by Catholic artists, but others less famous are alluded to, well worth an internet search: Ricci’s astonishing portrait of Tsunenaga Hasekura – key to Kokura’s story – is just one. To adapt the author’s own words elsewhere, we look at the paintings ‘as a divine world, helping us men to learn, and dwell, serve, grow and be saved.’

See more of Fr de Malleray’s books here.

Originally published in the Mass of Ages Autumn 2023 Edition: https://lms.org.uk/magazine.