“Destroy the Four Olds.” This slogan was central to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, launched in Beijing in 1966. What were the Four Olds? Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Habits and Old Customs. The destruction began simply, with the renaming of streets, stores, and even people, who exchanged their traditional Chinese names for revolutionary ones like “Determined Red.”

But violence soon followed. Red Guards broke into the homes of the wealthy to destroy books, paintings, and religious objects. Places of historical significance were destroyed or forbidden to the public. Cemeteries containing notable pre-revolutionary figures were vandalized, their graves desecrated. Old customs surrounding marriage, festivals, and family life were forbidden. Temples and churches were pulled down or put to secular use.

Why? Why was all this necessary?

Because, as Mao understood, the traditions of the past had to be destroyed to make room for new ideas, new culture, new habits, new customs. In short, for communism—so alien to traditional societies that people strongly rooted in their cultural and religious identity are psychologically incapable of accepting it.

A comparison between the campaign against the Four Olds to the campaign waged against the traditional Catholic Latin Mass over the last 50 years is not entirely fair; for one thing the element of physical violence is absent. Yet we must remember that the Cultural Revolution started without violence: simply renaming everything, assigning a new identity to everything; simply cutting people off from their cultural and religious heritage.

So no one, Catholic or not, who considers himself conservative can see the Catholic Church’s strange, self-sabotaging attempt to rid itself of its old traditional Latin Mass without concern.

All serious historians are aware of the enormous influence of the Catholic Church in the development of Western civilization. At the heart of the Catholic Church burns, like a furnace, the Catholic Mass, its defining act of worship and its source of energy. This Mass was the force that built cathedrals, monasteries, hospitals, and universities. It brought about the age of chivalry and the age of the Baroque. It was the unifying inspiration that caused Europe to spring up from the remains of the Roman Empire, shaping all of Western society as a result.

It’s obvious to any objective bystander that this Mass is an essential part of the Church’s history and identity. So why has the Vatican been trying to get rid of it, off and on, for half a century—most recently in Pope Francis’ July 16 motu proprio, Traditionis custodes?

In this document, Francis gives orders calculated to phase out the traditional Mass at the bishops’ earliest convenience, leaving ordinary Catholics cut off from their traditional form of worship.

It’s only the latest setback in a series of ups and downs for the Old Mass over the past 50 years. In 1969, Paul VI promulgated the modern rite most Catholics attend today. It was designed by a commission whose mandate was to ensure accessibility for modern Catholics and Protestants alike, and to express certain ideas that had come into favor in the 1960s during the Second Vatican Council. Use of the old rite was forbidden, with vanishingly rare exceptions.

Most people accepted this, some filled with the rosy optimism that was a hallmark of Catholicism in the 1960s, others out of a spirit of obedience that, in hindsight, may have been exaggerated beyond its legal requirement.

But a handful resisted. They believed the Vatican had no right to cut Catholics off from their sacred traditions. Their priests continued to offer the old Mass: not, they said, in defiance of the pope, but out of loyalty to the Church of all time.

Under the pressure of this growing movement, the Vatican softened its hardline position, though only somewhat. Then in 2007 Pope Benedict XVI sent shockwaves through the Church by affirming—as the resistors had argued—that the Old Mass was not forbidden and never had been. “What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful,” he wrote. The traditionalist star was in the ascendant.

Fast-forward to 2021, and the brakes have been slammed back on. The traditional Mass can only be said with special permission; bishops are to discourage it; all Catholics are gradually to return to the exclusive use of the modern rite. Goodbye, old ways.

You’d think more pressing issues plague the Church today: financial scandals, abuse scandals, threatened schism in Germany, the persecution of Catholics in China…Yet the ancient identity of the Church—preserved, moreover, only by a small minority–is singled out for the wrecking ball.

The crackdown is doomed, of course. It’s not 1969 anymore, and the papal flipflopping on the issue—Benedict says yes, Francis says no—shows a lack of seriousness from the Vatican that will be reflected in traditionalists’ response.

Like the resistors back in the 70s, they’ll argue that the Church doesn’t have the right to condemn its own sacred tradition. Eventually a favourable pope will come along. The Catholic Church thinks in terms of centuries, after all.

But for the present, those who dislike totalitarianism should sense their internal alarms going off. The Cultural Revolution teaches us that contempt for our Olds results in a loss of collective sense of identity. We need our past, as a child needs to know who his parents were, as a nation needs to know its history. We need—we have a right to–our sacred traditions. Non-Catholics who look to the Church have a right to expect the Church to maintain its identity, to be the protector of civilization and morality it has always been.

Who are we, cut off from our Old Mass, our ancient identity?

The Chinese could tell us. We are whatever the most powerful force of the day decides. And that’s terrifying.

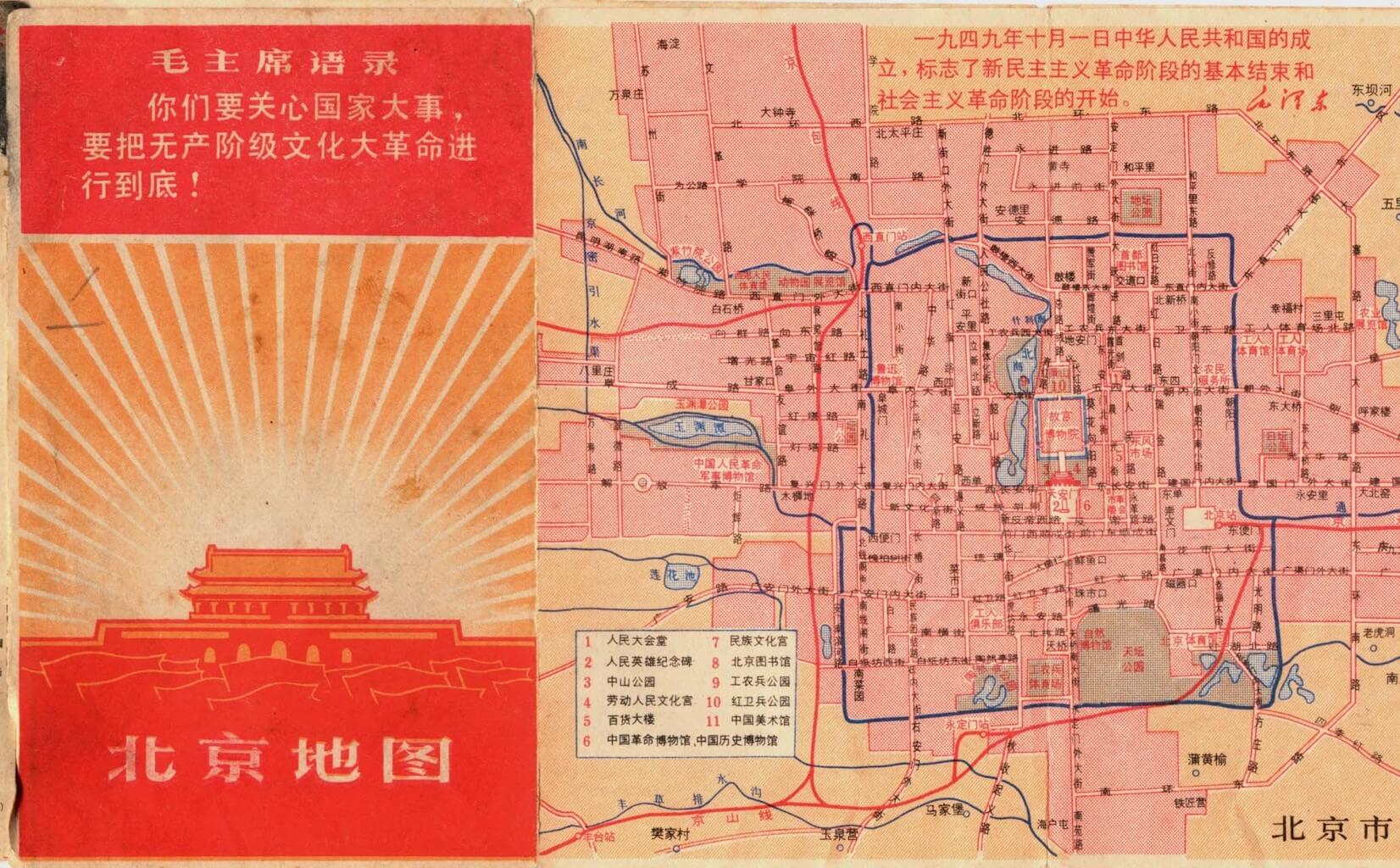

[Image: A 1968 map of Beijing showing streets and landmarks renamed during the Cultural Revolution.]