“Imagine there’s no heaven / It’s easy if you try / No hell below us / Above us only sky / Imagine all the people / Living for today…

Imagine there’s no countries / It isn’t hard to do / Nothing to kill or die for / And no religion too / Imagine all the people / Living life in peace…”

– John Lennon, Imagine

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

– Karl Marx

When Saint Thomas More wrote Utopia, he is attributed with having coined the term from the Greek οὐ (“not”) and τόπος (“place”) which together mean “a place that is not” – a fantasy that doesn’t exist. I relegate the task of evaluating the work itself to those individuals with better attention spans than I possess; I found it impossible to get through. But the title of this work (by a man put to death by a king who was playing at creating his own personal utopia) has become synonymous with those idealized visions of society in the mind of every dreamer since.

“You may think that I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one,” sang John Lennon. And he’s right – the world is certainly full of these kinds of dreamers. Not a few of them were madmen, and some of the ones who weren’t at times encouraged and empowered madmen with their radical ideas of what might be. Lennon himeslf once said of his most famous song, “‘Imagine that there was no more religion, no more country, no more politics,’ is virtually the Communist manifesto, even though I’m not particularly a Communist and I do not belong to any movement.” In this, he sounded a bit like Karl Marx, who once quipped, “if anything is certain, it is that I myself am not a Marxist”. But utopian ideas tend to take on a life of their own, regardless of the distance those who create them would like to place between themselves and the fantasy they pine for. Lennon, God rest his soul, was murdered by a man who thought him a blasphemer and a communist; Marx died stateless and barely mourned, but he managed to leave quite the legacy nonetheless, having inspired despotic regimes responsible for the death of some 100 million people across the world.

It isn’t merely Communism, of course, that embodies the dark side of utopianism. One can find its strains in any number of movements, from certain garden variety social justice campaigns to the Aryan National Socialism of the Nazis (and their kindred spirits in the Eugenics movement, like Margaret Sanger) to the wild and weird thinkers of the Transhumanism, some of whom are now anticipating the integration of human consciousness into machine constructs in the near-term future.

In an Easter Sunday homily, I heard about a special feature in this past weekend’s Washington Post, which examines new advances in medical technology being driven by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs in the mode of the fictional tech billionaire Tony Stark. These wealthy individuals are seeking to use their money to fund the scientific hijacking of biological evolution in order to “try to escape it or transcend it.”

Oracle founder Larry Ellison has proclaimed his wish to live forever and donated more than $430 million to anti-aging research. “Death has never made any sense to me,” he told his biographer, Mike Wilson. “How can a person be there and then just vanish, just not be there?”

During the first stage of their careers, the technologists spent their time solving problems in an industry that might seem glamorous but that in the grand scheme of things has been built on automating mundane tasks: how to pay for a book online, stream a TV episode onto a phone and keep tabs on friends. In contrast, they describe their biomedical research ventures in heroic terms reminiscent of science-fiction plots, where the protagonist saves humanity from destruction through technological wizardry.

Their confidence in that wizardry and their own ideas may lead them to underestimate the downsides and even dangers of the work they are funding, say some science philosophers, historians and economists. Their research in stem cells, neuroscience, genetically modified organisms and viruses, for example, tinkers with nature in big ways that easily could go awry — and operates in a largely unregulated space.

Their work to slow or stop aging, if successful, is also likely to lead to broader societal upheaval, increasing pressure on natural resources and on the economy, as people live longer, work longer and imperil already strained entitlements such as Social Security. Life extension also would radically change the most important building block of society: the family. No one seems able to predict what life might be like when half a dozen or more generations are alive simultaneously.

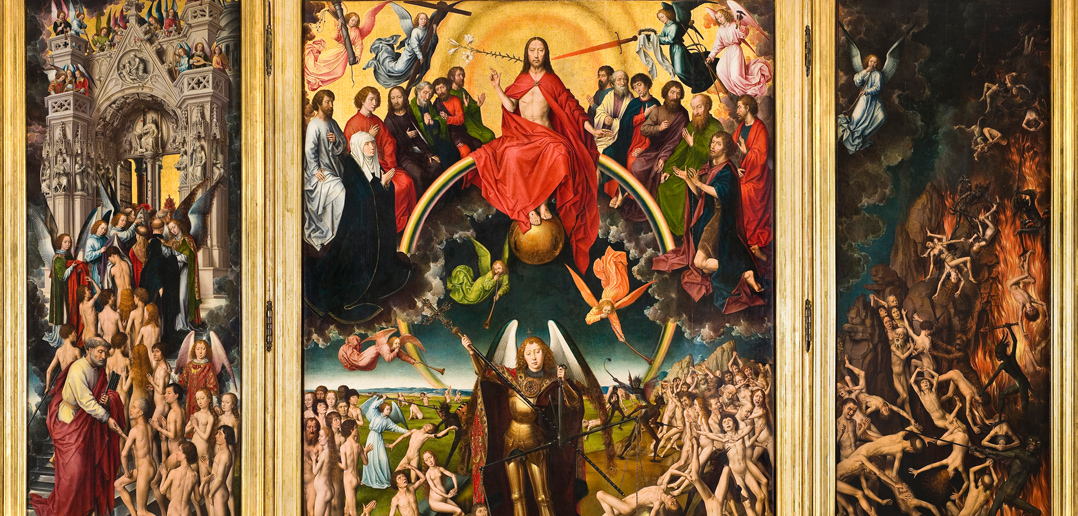

The common thread running through all of these movements should be obvious to the reader grounded in Christian faith: the fear that there is nothing after death leads people to do almost anything they can to try to create heaven right here on Earth. For Catholics, who have now embarked upon a new liturgical season, we have just experienced the Easter Triduum – the single most important reminder that the only way to truly conquer death is to embrace the wood of the cross; to bear our sufferings even unto the tomb, because if we love Him and follow His commandments, then like Christ we will be raised up again to spend an eternity in the Beatific Vision of God.

This is where our aspirations should be. This is where our effort should be made: not just on extending our life or improving its quality, but on preparing for a good death. There is nothing wrong with seeking cures, alleviating needs, or reducing suffering. In our compassion for others, we should do these things. But if we do these corporal works of mercy out of an avoidance of the inevitable, and to the exclusion of the spiritual works of mercy; if we seek to make this life perfect because we question or even refuse to believe in the afterlife, we are committing a form of idolatry.

Beware the architects of technological immortality. Beware the endless pursuit of luxury and comfort. Beware those who seek political solutions to spiritual problems, or to replace the existing civil order with an ideological fantasy. Beware those who speak only of the material needs of the poor, but never of the requirements of their salvation. Jesus did not suffer and die and rise from the dead to eradicate poverty or hunger, to create an endless life without suffering for us on earth, or to establish a perfect earthly kingdom.

He came so that “whosoever believeth in him, may not perish, but may have life everlasting.” (John 3:16)

The reality is that technology, political philosophy, and human creativity can only take us so far. Adam and Eve were banished from the earthly paradise that was Eden because even in their perfected, preternatural state, they were unable to resist temptation and sin, and thus needed a redeemer. Do we believe we would have fared better? Do we think we can now recreate by our ingenuity what they lost for themselves and their posterity through The Fall?

Our motto should be “Memento Mori,” as it was for so many of the saints. Remember that you will die. This world can take from us our health, our wealth, and everything we possess. And in death — which comes for us all — we leave all these temporal things behind. The only thing we get to bring with us — the only thing no one can take from us — is our soul.

Is yours ready?

Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur,

Mors venit velociter quae neminem veretur,

Omnia mors perimit et nulli miseretur.

Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.Life is short, and shortly it will end;

Death comes quickly and respects no one,

Death destroys everything and takes pity on no one.

To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus

Et vitam mutaveris in meliores actus,

Intrare non poteris regnum Dei beatus.

Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.If you do not turn back and become like a child,

And change your life for the better,

You will not be able to enter, blessed, the Kingdom of God.

To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.– Ad mortem festinamus of the Catalan Llibre Vermell de Montserrat; 1399