Some of the fondest memories I have from my childhood are of doing math and science projects with my dad. My father is a carpenter by profession and so our basement was and is filled with wood and metal, power tools and fasteners of all kinds. We readily put these scraps to use on such projects. Among other things, we built and flew model rockets together. Later my parents bought me a telescope with which I was able to see the planets, and even some of their larger moons. In short, a fascination with physics, astronomy, and the sciences in general has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. And while I “grew-up” to become a biologist, I maintain a hobbyist’s interest in things space related.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that over the past year I have watched with great excitement the dawning of what has been informally dubbed the “second space race” (some regularly updated YouTube channels on these developments are Everyday Astronaut and What About It!?). If this is news to you, let me explain. As is well known, in the first space race, the United States and the Soviet Union competed to put the first satellite in orbit, the first living thing in orbit, the first man in orbit, the first woman in orbit, the first object on the moon, and the first man on the moon. The Soviets won the first five, the Americans the sixth. In this second space race, it is not national governments but private companies that are competing to be the first to do all of these same things, as well as take humans to Mars for the first time. Among the companies “in the race” are some familiar names such as Boeing and the Virgin Group, but also possibly lesser-known names such as Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, United Launch Alliance, and SpaceX. The ultimate outcome will be the commercialization and privatization of outer space.

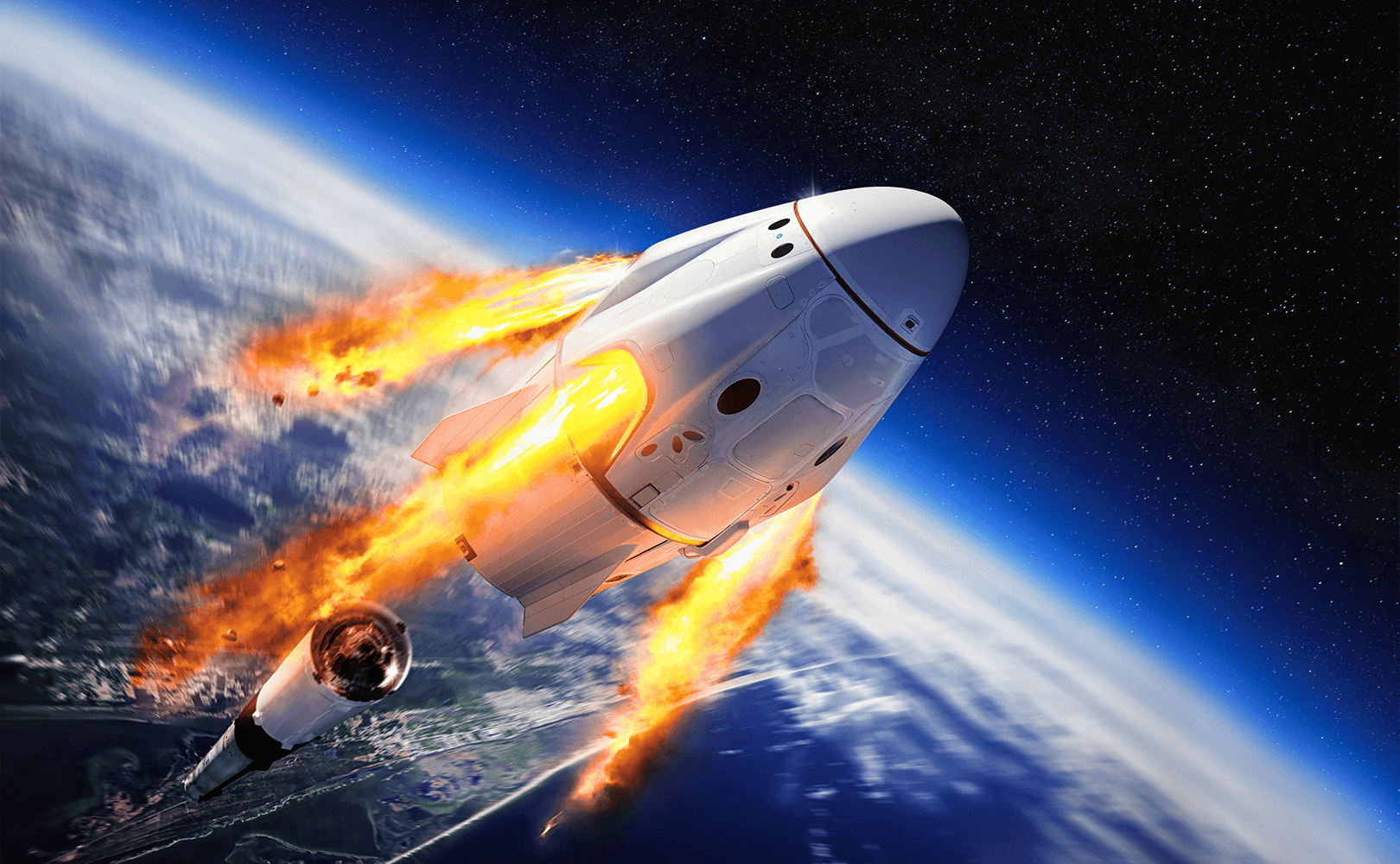

Among the various companies, SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk, is the clear frontrunner. Musk is motivated by what is essentially the desire to have a human back-up disk. Natural disasters have caused mass extinctions on Earth in the past and will likely do so again in the future. If humans have settlements outside of Earth (on the Moon or Mars), the human species can survive such tragedies. Musk, best known for being one of the co-founders of PayPal, is very serious about this and plans to use SpaceX like a spacefaring East India Company in order to do it. Since leaving PayPal, he has sunk nearly all of his considerable personal fortune into Tesla (his electric car company) and SpaceX. While it remains to be seen if he will succeed in colonizing the Moon and Mars, it is clear he is going to try. In fact, SpaceX is on-schedule to put boots on Mars and the Moon within the next five to ten years. The vehicles that will do this are already under construction at the SpaceX testing facility in Boca Chica on the Gulf Coast of Texas. The first SpaceX flights to Mars are scheduled for 2022 (robots and supplies) with the first people scheduled to depart Earth in 2024. And this will be no mere visit. SpaceX plans to send new permanent colonists and supplies regularly (multiple rocket launches per day) in the years that follow in order to build the first functioning Martian city by 2050.

I write about all of this not only because it is exciting, but also because Catholics will naturally want to be a part of these new voyages of discovery, just as we were part of the first major voyages of discovery. The thought of the first ever Mass on the Moon or Mars is an exciting thing to ponder. Similarly, it will be a very happy day when the title “Bishop of Mars” becomes a real thing. Or, maybe it will be “Bishop of Orlando and Mars” following the traditional custom that new ecclesiastical localities fall under the jurisdiction of the see from which the mission was sent. (NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, where SpaceX currently launches from, is located in the Diocese of Orlando, Florida.)

If a lunar (Moon) or Martian city are ever built, we will want to establish a permanent clerical presence there as soon as possible to continue to bring the Gospel not just to the whole world, but to the whole solar system, galaxy, and universe. Yet, taking Catholicism to the stars will not come without its difficulties. Unlike during the first voyages of discovery, those bankrolling the missions will not be devout Catholics, Christians, or in many cases even deists. Thus, there will be first and foremost the task of justifying our presence. While these colonizing missions will include many more people than past missions, the organizers will be paying for payload weight at a premium price per pound, and will not be interested in subsidizing “dead weight,” that is, persons who cannot contribute to the day-to-day upkeep of the city in an unforgiving environment. Sadly, in the best-case scenario, most will view priests as just that. Thus, it is likely that the first priests who go into space will need to be chosen from among what we might term, “second career” priests. These are men who discovered their vocations later in life and therefore have a past life and experience as a mechanic, electrician, engineer, or plant propagator. These men will then be able to make a useful contribution to the day-to-day matters in the city. Each will need to be the Saint Paul of the Third Christian Millennium, supporting their preaching efforts through the practice of their trade.

A second major problem will be that of enculturation. While we don’t expect to find non-human intelligent Martian life to evangelize, differences in the natural properties of these new worlds as well the circumstances under which they are colonized may require prudential alterations in Catholic practice.

First, it is likely that open flames and smoke will not be allowed, certainly on space ships or space stations, and likely not on a Martian or lunar base either. When a fire breaks out on a space station, there is nowhere to run. Moreover, fires consume the oxygen that humans need to breathe. Thus, rubrics will likely need to be introduced to remove candles and incense from the rites of lunar and Martian missals. It has been speculated that Mars can be terraformed. Terraformation is the process of transforming another planet to sustain life as Earth does. Principally, this means altering the atmosphere of a non-Earth planet (or moon) to make it habitable. At that point, humans could walk on the surface of the planet without the need of a space suit, and plants and animals from Earth could be introduced. Once terraformed, presumably candles and incense could return to the Martian liturgy.

A second major concern will be that of gravity. The gravity on Mars is roughly one third that of Earth. Gravity on the Moon is even lighter, roughly one sixth that of Earth. Thus, special care will need to be taken in liturgical action. Jerky motions or motions applying a force equivalent to the production of the same Earth motion will likely cause problems. For example, too rapid an elevation would cause the Precious Blood to leap out of the chalice or particles of the Host to be scattered. Thus, lunar and Martian liturgies will likely be noted for their slow speed and delicacy. Further, Masses would likely be prohibited in zero-gravity due to the inability to collect Eucharistic particles or keep the Precious Blood in one place.

A third concern will be the treatment of the dead. It would be possible to bury the dead in the lunar or Martian surface, but with some limitations. It would be very difficult to perform any rites associated with the preparation of the grave, the burial, or the future care of the grave. No holy water could be used as it would freeze and sublimate (transform from a solid into a gas without first becoming a liquid). Further, because there is nothing living in the Martian soil (that we know of), the bodies would not degrade. Everyone would be incorrupt! As a result, and in order to better facilitate the care of the dead and frequent visitation to the grave sites for prayer, it may be necessary to use an artificially accelerated form of secondary burial. Secondary burial is the practice of burying a body for long enough to allow the soft tissues to decompose, exhuming the body, collecting the bones, placing them in a smaller box, and laying them permanently to rest in an ossuary. This is a traditional practice already approved by the Church. Ordinarily, this process can take up to a decade or more, but with indoor space at a premium, the process could be accelerated by making the primary burial in a kind of decomposition chamber with high heat and high biological (i.e. bacterial/fungal/enzymatic) activity, thus dissolving the soft tissues quickly, even on the span of days. The bones could then be collected and prepared for the ossuary. This would be a more acceptable alternative to incinerating the bodies. Accelerated biological degradation would also have the advantage of producing a usable, nutrient rich soil as a byproduct.

It is possible that the enculturated element of a spacefaring Catholic civilization that will be most noticeable is its liturgical calendar. This would manifest itself differently on the Moon and on Mars. On the Moon, one year (traveling around the Sun one time) is the same length of time as one year on the Earth because the Moon orbits the Earth. The two travel together. The lunar day (the time it takes for the moon to rotate once on its axis), however, is very different from a terrestrial (Earth) day. In fact, a lunar day is the same as one month on Earth. Given this wide discrepancy, it is likely humans will simply impose an artificial day length of 24 hours for those living on the Moon. As with places such as Alaska, the daily cycle of light and darkness would be created artificially by window shades and full spectrum lamps. Thus, it is likely that no major calendar revisions would need to be made in the lunar missals.

Mars is a different story. The Martian day (the time it takes Mars to rotate once on its axis) is actually very close to that of Earth, at about 24 1/2 hours. As with the Moon, and for the sake of consistency, it is likely that humans will coerce this into a 24-hour day. Here it would be accomplished by extending the length of each second by about 2%, for all the clocks on the Martian surface. This would likely be unnoticeable and allow for the retention of a familiar daily cycle. The Martian year (the time it takes Mars to travel once around the Sun) is a bigger problem. Mars has a year that is about 687 Earth days long. This is further complicated by the fact that Mars also has a tilt in its rotational axis (like Earth). The result is that Mars, like Earth, has seasons: spring, summer, fall, and winter. It gets darker and colder in the winter and lighter and warmer in the summer, etc.

What does this mean for the Martian liturgical calendar? Catholic timekeeping is based on a hybrid of both solar and lunar calendars. While the date of certain feasts is calculated by the lunar calendar (i.e. Easter), this is done in the context of the larger solar calendar, such that Easter always falls in the springtime. This same practice is true of the Hebrew calendar, specifically with respect to Passover. Islam, on the other hand, does not reference the solar calendar in its timekeeping, calculating the dates of feasts purely based on the lunar calendar. This is why Ramadan, for example, can occur at any time of the year and will occur twice in 2030 (the lunar months mismatch the solar year by about 10 days, i.e. 12 lunar months only yields about 355 days).

The question is ultimately whether to enculturate the Martian liturgical calendar to the Martian solar calendar or keep the terrestrial solar calendar. In other words, would the Martian missals have liturgical calendars that cycled through one Martian year (i.e. a 687-day calendar)? Or, would Martian missals retain the 365-day Gregorian calendar they currently have and simply fall out of sync with the Martian solar calendar and the Martian seasons? If enculturation to a Martian solar calendar is chosen, would certain major feasts (like Christmas) become movable to adequately reflect their historical nature? If this were to happen, it would be possible for one solar year on Mars to have multiple Christmases.

Some evidence as to how the Vatican might rule on this could be drawn from how the Southern Hemisphere of Earth is treated. While acknowledging the symbolic nature of Christmas occurring during the winter (the play of dark and light), the Vatican did not give the Australians, South Africans, Argentinians, et al. an inverted liturgical calendar to match feasts with their analogous solar season. Rather the liturgical calendar in the Southern Hemisphere keeps the absolute dates of feasts in order to emphasize the historicity of Christianity. Jesus is born on December 25, not June 25. Thus, even though the symbolic quality of light being born in the midst of darkness is lost on Southern Hemisphere Catholics, the fact that the Logos entered the creation order as the real historical person Jesus Christ on December 25 is preserved. The difference with Mars, of course, is that Jesus was not born on Mars. There is no absolute Martian date for the birth of Jesus because the relationship between any arbitrary Martian calendar to the solar terrestrial calendar would itself be arbitrary. In that case, perhaps it makes more sense to reconfigure the Martian missals to better account for the Martian solar calendar.

Discussions of such things could go on to book length. In the end, only time and experience will show how Catholicism enculturates to life outside of Earth. Surely there will be many growing pains as Catholicism becomes interplanetary. It is a fun diversion to speculate on hypotheticals such as these. It is even more fun knowing that, within my own lifetime, they may not be hypothetical after all.