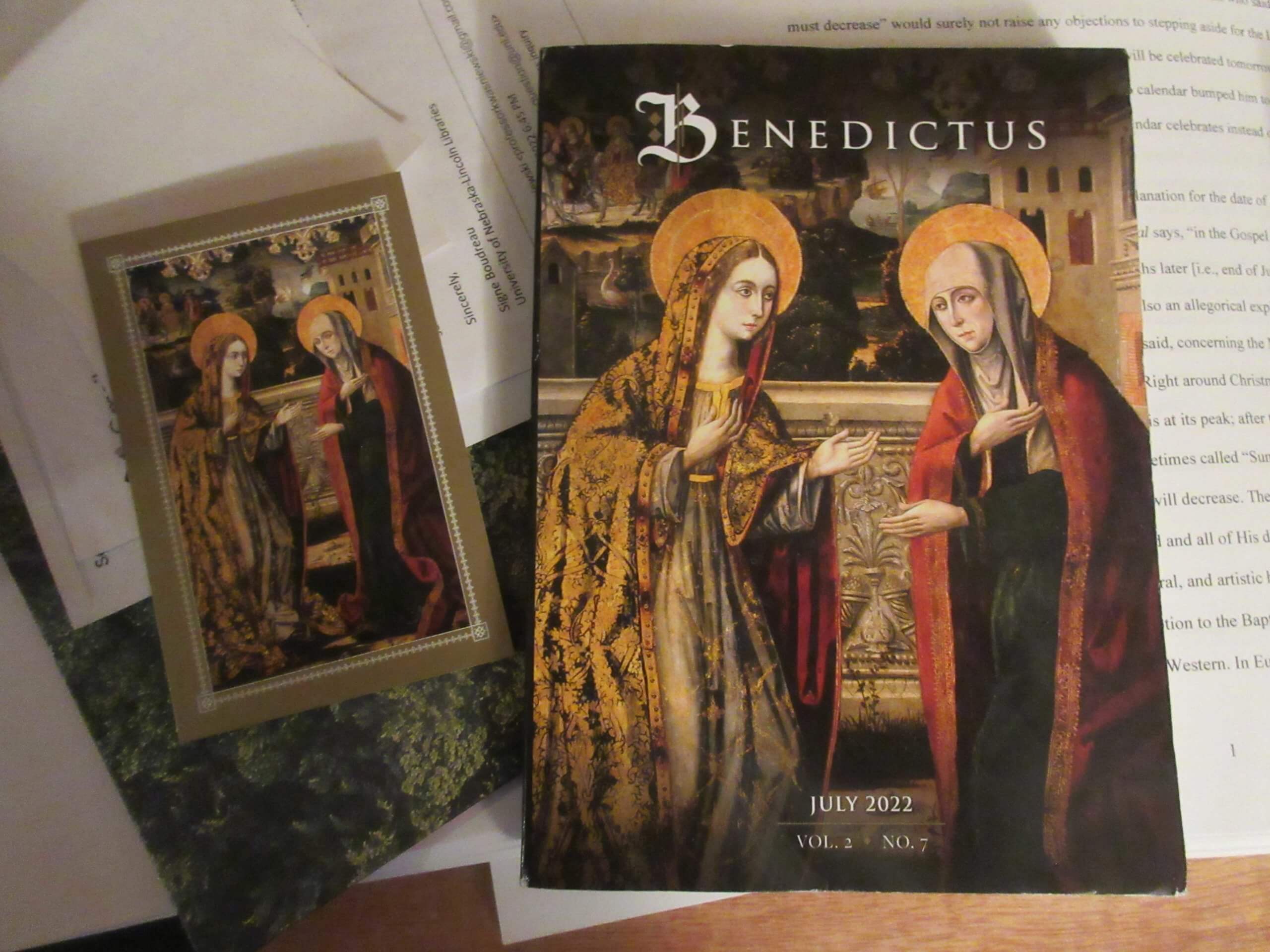

Above: The Visitation by Flemish painter Willem Vrelant (d. 1481).

Today, July 2, is the usus antiquior feast of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This feast was instituted in 1389 by, in a way, two popes—Pope Urban VI as the one who intended to institute it, in hopes of obtaining the end of the Great Western Schism, and Pope Boniface IX who actually signed the decree, since Urban VI had died before he could carry through.

The feast was placed at that time on July 2. There it remained until 1969, when it was moved to May 31, so that—according to the architects of the new calendar—by lying “between the Solemnity of the Annunciation of the Lord (25 March) and that of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (24 June), it would harmonize better with the Gospel story.” In Germany, Slovakia, among some Anglicans, and, of course, among traditional Catholics, the original date is retained.[1] The most recent issue of Benedictus, the TLM parallel to Magnificat, boldly features a painting of the Visitation on the cover of its July issue.

The reformers’ justification for moving it from July 2 to May 31 is curiously literalistic. While the Church calendar does sometimes observe exact chronological sequences (e.g., March 25 to December 25 is nine months, and December 8 to September 8 is nine months), the calendar is usually rather heterogeneous, more concerned with reasons of mystical fittingness than with adhering to a natural order. It is, in other words, founded on the supernatural order, not on a simple chronological sequence. Often enough, too, feasts are instituted on dates of historical significance, such as victories in battle, when God reveals Himself anew, for He is not limited to Scripture but ever at work in the Church.

In this case, one can discern the wisdom in having a feast of Our Lady following the feasts of St. John the Baptist, Saints Peter & Paul, and the Precious Blood of the Lord. If there were no Mary, there would be no Jesus; if no Jesus, no John, Peter, or Paul. In God’s plan to redeem the world, she is the punctum saliens, the starting point on the side of creation. In the month of June, rejoicing in the greatest man born of woman (June 24), the greatest Apostles appointed by Jesus (June 29), and finally the greatest outpouring of love on the Cross (July 1), we arrive at the greatest creature through whom all of this was made possible. No Mary, no Jesus, no Baptist, no Princes.

Why, then, the mystery of the Visitation in particular? It is a mystery of “going forth”: the Word already proceeding, carried by His Mother. The Precursor went forth before the Lord. The Apostles went forth to preach and die in Rome. The Blood of Jesus went forth from His Body, and, in baptism and penance, His Blood is visited upon us. “Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel; quia visitavit et fecit redemptionem plebis suae” (Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and wrought redemption for His people) as Zecharias proclaimed in the Benedictus. When we arrive at July 2, we come to the primordial going forth that sets the pattern for all the rest. That is why it comes last.

July 2 is also the day after the octave of the birth of St. John the Baptist.[2] The Baptist was circumcised on the eighth day and received his name. One may presume that Our Lady and St. Joseph waited for that event, and then went home. The Visitation of Our Lady to Elizabeth was simultaneously the visitation of Our Lord to His cousin in the womb, which sanctified him. The mystery of the sanctification of John in the womb is explained by the Visitation that caps off the octave.

In his great commentary The Liturgical Year, Dom Prosper Guéranger asks why the Visitation of Our Lady, in particular, was chosen as the feast that would commemorate the reconciliation of the warring factions of fourteenth-century Christendom, the healing of the Great Schism. He offers this explanation:

Here, more particularly, does Mary appear as the Ark of the Covenant, bearing within her the Emmanuel, the living Testimony of a more true reconciliation, of an alliance more sublime between earth and heaven, than that limited compact of servitude entered into between Jehovah and the Jews, amidst the roar of thunder. By her means, far better than through Adam, all men are now brethren; for He whom she hides within her is to be the First-born of the great family of the sons of God. Scarce is he conceived than there begins for him the mighty work of universal propitiation….

Let us then hymn this day with songs of gladness; for this Mystery contains the germ of every victory gained by the Church and her sons: henceforth the sacred Ark is borne at the head of every combat waged by the new Israel. Division between man and his God is at an end, between the Christian and his brethren! The ancient Ark was powerless to prevent the scission of the tribes; henceforth if schism and heresy do hold out for a few short years against Mary, it shall be but to evince more fully her glorious triumph at last.

“If schism and heresy do hold out for a few short years against Mary”—do not these words apply to the twenty-first century, when virtual schism and flagrant heresy dominate, more vividly than ever they did before!—“it shall be but to evince more fully her glorious triumph at last.” Or, in the words that Our Lady herself made familiar to us: “In the end My Immaculate Heart will triumph.”

In the mean time we hail her in the ancient prayers of the Church, so unfashionable today, yet all the more necessary in proportion as men deny the truth on which these prayers are founded: “Dignare me laudare te, Virgo sacrata: da mihi virtutem contra hostes tuos” (Deign to let me praise thee, O sacred Virgin: against thy enemies give me strength) and “Gaude, Maria Virgo, cunctas haereses sola interemisti” (Rejoice, O Virgin Mary, thou alone hast destroyed all heresies).[3]

This article was originally published in the year of Our Lord’s reign MMXXII.

[1] For a full account of the fascinating history of the feast, see Gregory DiPippo, “Liturgical Notes on the Visitation of the Virgin Mary.”

[2] Back when there were still octaves, before Pius XII slaughtered all but three.

[3] The first prayer is the versicle after the Marian antiphon “Ave Regina Caelorum”; the second is from the Tract of the Mass of the Blessed Virgin Mary, “Salve Sancta Parens.”