Pre-Lent is nearly at an end with this Quinquagesima, “Fiftieth” Sunday. The Forty Day discipline of Quadragesima will soon begin with Ash Wednesday and more intensely still with the 1st Sunday of Lent. Today, as with the previous Alleluia-less, purple Sundays, we go in our hearts with myriads of our forebears to the Roman Station, the mighty Vatican Basilica. As Bl. Ildefonso Schuster, the great liturgist of Milan puts it,

having assured ourselves of the patronage of St. Lawrence, St. Paul and St. Peter, we shall be ready with full confidence to commence next Sunday at the Lateran Basilica the holy cycle of penance.

Our Gospel reading for this Sunday is the Lucan announcement of the approaching Sacrifice of the Lord, who was moving ever closer to Jerusalem. This year in these columns, however, we are looking into the Epistle reading. Given the awesome content of the reading from St. Paul, I almost wish I could deal with something as “simple” as Christ calling heading to Jerusalem to die. And then healing a blind man.

Our Epistle reading is from 1 Corinthians 13:1-13, which is the great paean of the Apostle to charity. It is probably the most famous of all the famous passages from Paul’s letters.

Last week we heard about Paul’s actions and sufferings. He had been granted by God a “thorn” to keep him humble after he was taken up for a mystical visit of Heaven, where he heard “things that cannot be told, which man may not utter” (2 Cor 12:4). Perhaps what we hear in the Epistle today reflects something of that celestial experience.

I’ll help myself out, and you with me, by using extended quotes about this passage from those far above my paygrade. First, we should have the pericope in full.

Brethren: If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give away all I have, and if I deliver my body to be burned, but have not love, I gain nothing.

Love is patient and kind; love is not jealous or boastful; it is not arrogant or rude. Love does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrong, but rejoices in the right. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.

Love never ends; as for prophecies, they will pass away; as for tongues, they will cease; as for knowledge, it will pass away. For our knowledge is imperfect and our prophecy is imperfect; but when the perfect comes, the imperfect will pass away. When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became a man, I gave up childish ways. For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood. So faith, hope, love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.

It is important simply to let these words seep in. Back up to chapter 12 and then start reading aloud.

In his monumental The Liturgical Year (vol. 4), the Abbot of Solesmes, Prosper Guéranger, wrote about Paul on charity:

This virtue, which comprises the love both of God and of our neighbour, is the light of our souls. Without charity we are in darkness, and all our works are profitless. The very power of working miracles cannot give hope of salvation, unless he who does them have charity. Unless we are in charity, the most heroic acts of other virtues are but one snare more for our souls. Let us beseech our Lord to give us this light. But let us not forget that, however richly He may bless us with it here below, the fullness of its brightness is reserved when we are in heaven; and that the sunniest day we can have in this world, is but darkness when compared with the splendour of our eternal charity.

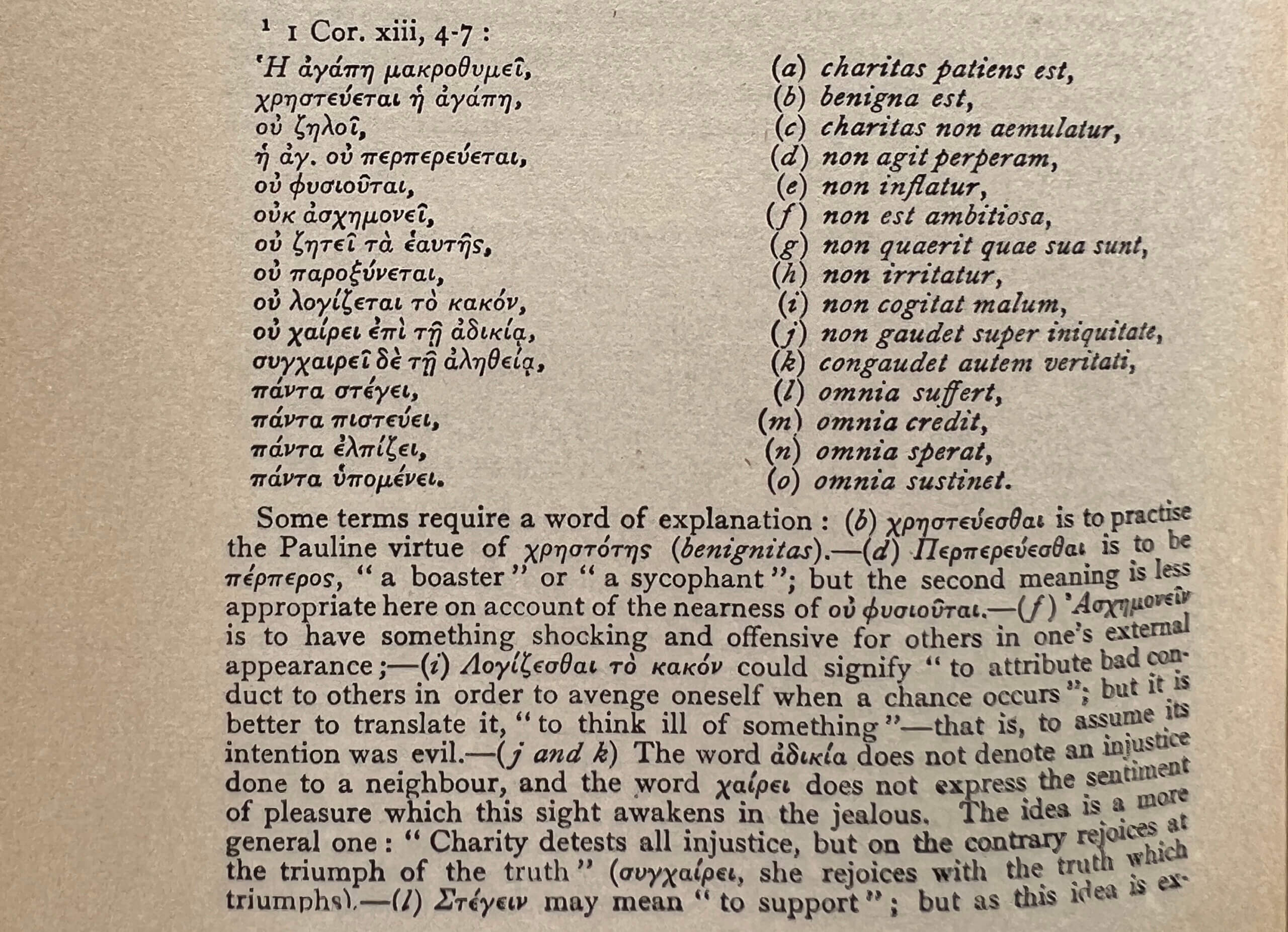

A great scholar of St. Paul, Fr. Ferdinand Prat, SJ, in his massive, two-volume work on The Theology of St. Paul, breaks down the hymn to charity, identifying fifteen virtues that accompany this kind of love. However, he warns: “We will not try to classify these fifteen virtues, the companions of charity. By seeking to find in them a strict order, our exegesis would be sacrificed to a system.”

Prat says that our passage today is “clearness itself” and “any commentary would only obscure it.” So, there. My work is done.

That said, Prat does make useful observations. He comes from a day when people could still get to the point. Prat sorts the most important ideas into three categories.

Before we get into that, we need two tools. First, without going into vast depth, the word in Greek Paul uses for charity or love is agape which we can characterize as love we have for another that seeks always the good of the other even to the point of self-sacrifice. This is a higher love than what other Greek terms can mean for “love” such as eros (used by philosophers but is not in the New Testament – for erotic love between men and women), storge (by which we love Fluffy the cat or have fondness for an acquaintance), and philia (friendship between equals such as a brother or close friends … these days often distorted into something decadent and degrading, masquerading as “love).

For an additional tool, we observe that in the verse immediately preceding our reading, 1 Cor 12:13, Paul, after describing flashier gifts from God such as healing and interpretation of tongues, writes: “Earnestly desire the higher gifts [Greek charistmata]. And I will show you a still more excellent way [Greek hódos].” Charisma has a great range of meanings, but it is essentially something received from God without any merit of our own. Sound familiar? It is a “grace,” unmerited “gift,” which can be saving in the case of habitual grace and ad hoc, actual graces which enable us to serve God and the Church in this or that way. Paul, in 1 Cor 13, moves from the actual to the habitual, which means the theological virtues of faith, hope and love or charity, which is sacrificial love.

That said, we can go back to Prat for help with our passage:

Charity is the queen of virtues. Charismata are indeed precious gifts and must be estimated at their full value, preference being given to the most useful rather than to the most brilliant. But there is a way incomparably loftier and surer, the royal road of love. Without charity the most excellent of charismata are nothing and do no good. The gift of tongues is then a useless babble of words; prophecy is a passing gleam, which will be eclipsed at the day of the beatific vision. Charity alone will never fail. Faith and hope, which share with her the privilege of having God for a direct object, will disappear in heaven, where the elect see instead of believing and can no longer hope for what they already possess without the possibility of loss; but charity is immortal and does not change essentially in nature when transformed into glory.

Charity is the summary of the commandments, for it includes an implicit submission to the divine will in all its extent. The Master said: “On these two commandments (love of God and of one’s neighbour) depend the whole Law and the prophets.” The disciple said in his turn: “All the other commandments are comprised in one word: Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself…. Love, therefore, is the fulfilling of the Law.” And again: “For all the Law is fulfilled in this word: Love thy neighbour as thyself.” Or, with enigmatical conciseness: “The end of the commandment is charity.”

Charity is the bond of perfection. This it is which holds tightly together, like a sheaf of fragrant flowers, the virtues whose entirety constitutes Christian perfection. Or, to vary the metaphor, it is keystone of the vault designed to hold together all the stones and mouldings of our spiritual structure, which without it would crumble. St Francis de Sales tells us in his usual graceful style that “charity never enters a heart without also quartering therein all her escort of the other virtues.” The pious Bishop of Geneva appears to have drawn his inspiration from St Paul, who thus describes the train of the minor virtues which attend their sovereign.

Before I bring this to a conclusion, I want to circle back to that last word in the last verse of ch. 12, which is Paul’s segue: Greek hódos means “way, path.” He is saying, “those are one way and now here’s a higher path.” It seems to me that we should feel that word as meaning “way of life.” Paul is instructing Christians about how to live as Christians. That means that no Christian is exempted. What follows is a sine qua non, because – in Christ – we cannot “settle” for what is lower. We must keep our eyes on the prize (Heb 12:1), run to win (2 Tim 4:7), seek that which is above (Col 3:1).

The fact that it is a “path” suggests also a journey to a destination, not instant arrival. As we live a spiritual life, we grow. It is important to persevere in perfecting our love.

In that light, let’s bring in a Johannine text to shed light on our Pauline text. We summon to hand 1 John 4:7-12:

Beloved, let us love one another; for love is of God, and he who loves is born of God and knows God. He who does not love does not know God; for God is love. In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the expiation for our sins. Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. No man has ever seen God; if we love one another, God abides in us and his love is perfected in us.

“God is love.”

Is this a platitude or a way of life?

I’ll close with a point of reflection from Bl. Ildefonso in his remarks on this Sunday’s Epistle from Paul:

It is not possible for anyone easily to persuade himself into thinking that he loves the invisible God, if at the same time he does not love Him through those creatures who visibly represent him on earth.