This is the second installment of a multi-part series. You may find each part here: Part I – Part II – Part III

The printing press reduced the cost of book production in late medieval Europe enormously. But printed books did not altogether replace illuminated manuscripts, at least not in the years before the rise of Protestantism. To judge by such early 16th century masterpieces as the Books of Hours created for Anne of Brittany, manuscript illumination remained vital as an art, despite suffering as a business.

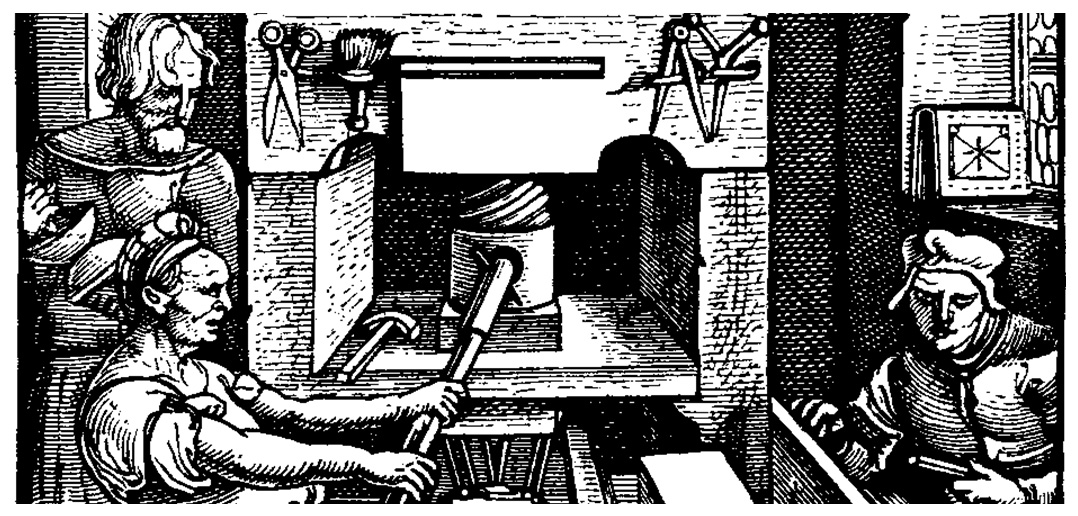

The illuminator’s art survived somewhat even in printed books themselves. The literate public’s expectations for book design were still formed by centuries of manuscript tradition; versals, marginal ornaments and pictures were considered essential, and artists working in woodcut or metalcut made beautiful ones for the early printers. There is nothing inherent in the technology of printing that demands such elements be eliminated; the reduction of the printed page in most books (for adults, anyway) to an unadorned rectangle of type is a sad development of later times. The so-called Printing Revolution of the 15th century was a technological and economic revolution, not an aesthetic one.

The only obvious artistic limitation of the new method was the difficulty of printing in multiple colors. Each color required a separate plate and ink, and printing the same sheets of paper or vellum again, lining up the registrations exactly. Because of this challenge, many incunabula had only the text printed; illuminators later added beautiful capital letters, decorative borders and illustrations in colorful egg tempera paint and gold leaf. These hybrid works are indistinguishable from manuscripts at first glance; a copy of Johannes Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible in the Lambeth Palace Library was mistaken for a manuscript for centuries.

Certain printed books of the late Middle Ages were hybrids of opposite elements: printed woodcut pictures and handwritten text. These books (called chiroxylographic) were made in times and places where the art of relief printing was practiced, but movable type was not yet invented or available. Other books published in the same circumstances had the text carved into the printing blocks; these are called xylographic. Books of either kind are called block books; the pictures in many were colored by hand.

For obvious reasons, the publishers of block books favored works in which pictures dominate. Popular subjects included the Apocalypse of St. John, the Dance of Death, the Apostles’ Creed and the Canticle of Canticles (interpreted allegorically as the marriage of Christ to Ecclesia). The prayers, thoughts, hopes and fears of the Catholic faithful have never been more strikingly depicted than in their wonderful pages. These are four of my personal favorites:

I. Biblia Pauperum

Symbolism pervades medieval art; this is one of its defining characteristics, nowhere more clear than in its juxtaposition of scenes from the New Testament with their Old Testament prefigurements. In recent times, the Old Testament has been studied mostly from an historical perspective, but the Fathers of the Church and the theologians of the Middle Ages preferred an allegorical exegesis. This was beautifully described by the art historian Emile Mâle:

God who sees all things under the aspect of eternity willed that the Old and New Testaments should form a complete and harmonious whole; the Old is but an adumbration of the New. To use medieval language, that which the Gospel shows men in the light of the sun, the Old Testament showed them in the uncertain light of the moon and stars. In the Old Testament truth is veiled, but the death of Christ rent that mystic veil and that is why we are told in the Gospel that the veil of the Temple was rent in twain at the time of the Crucifixion…. This doctrine, always held by the Church, is taught in the Gospels by the Savior Himself: As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up.

The Biblia Pauperum summarizes this theological tradition for the common faithful. On each of its (usually forty) pages, a particular event from the life of Christ is juxtaposed with two events from the Old Testament that prefigure it. The pictures are paired with rhymed Latin versicles and short explanations. Four prophets who foretold the event are included as well. For the Virgin Birth (shown below), the prefigurements are Moses before the Burning Bush and the Flowering of Aaron’s Rod; the prophets are Daniel, Isaiah, Habacuc and Micah.

II. Ars Memorandi

Intended to aid the faithful in memorizing the Gospels, the book contains a series of fifteen pictures of the apocalyptic beasts associated with the four Evangelists (St. Matthew’s man, St. Mark’s lion, St. Luke’s ox and St. John’s eagle). The rampant figures are adorned with and surrounded by numbered emblems corresponding in order to the events described by the inspired authors. One of the basic principles of mnemonics is that imagery must be strange to be effective; the illustrations in this book are memorable, to say the least!

III. Ars Moriendi

Following the great plague of 1347-51, death became one of the principal subjects of European art and literature. Many of these works, such as the Dance of Death, are terrifying and pessimistic. But this short book on the art of dying well, illustrated with eleven pictures, is profoundly consoling. The centuries since its publication have not lessened its relevance in the least.

It describes and depicts a battle between angels and devils around the bed of a dying man. The enemies tempt him first to doubt God’s existence; then to despair of God’s mercy; then to attachment to worldly concerns; then to anger with God for his sufferings, and finally to pride. Each time, the angels intervene, offering counterarguments to the demonic lies and encouraging the man to faith, hope, detachment, peace and humility; at last, they carry his soul to heavenly bliss.

IV. Exercitium Super Pater Noster

This is the shortest of the four works featured, consisting of ten illustrations with short accompanying text. It is also the rarest, surviving in only three copies (two of one edition, one of another). It is a product of the same allegorical literary tradition that produced morality plays such as Everyman. In it, an everyman figure (a monk named Frater) is instructed by an angel (named Oratio) on the meaning of the Lord’s Prayer. On their journey together they visit Heaven, Purgatory and Hell and meet personifications of the virtues and vices. The imagery here is subtle and complicated; a good translation and explanation of the work was published in 1989 by the medieval scholar Barbara Jaye.

Some of the block book illustrators were exceptional artists; one of the undisputed masterworks of art for the ages, the Albrecht Dürer Apocalypse of 1498, is essentially part of this tradition. But admittedly, some of the illustrators were decidedly unsophisticated. Yet even the crudest block books are lively and interesting; the artistic potential of their subject matter is proved in other media, such as the gorgeous tapestries owned by the Cathedrals of Rheims and Sens that recreate pages from the Biblia Pauperum in woven fabric.

The wealth of piety and imagination contained within these books is inestimable; and much of it has yet to be given its most perfect artistic expression. The block books cry out for revisitation by traditional Catholic artists of the present day.