It did seem as though many of the Synod fathers were proposing something that is logically impossible. It was not said out loud, but the implication was that they were asking, “Between yes and no, being and not being, sin and not sin, death and life, can we have a ‘third’ option? And if so, is this where ‘mercy’ lies?”

One of the reasons everything that went on at the 2014 session of the Synod on Marriage and Family has been so uncritically welcomed in the secular world and in the Church is that people are not taught any more the fundamental concepts of rationality. And the idea of a warm, cuddly, non-judgmental and “merciful” “third way” between condemning sin and total permissiveness, is certainly very appealing to people who have no notion of what the jiggety they’re talking about.

Or, as our friend Patrick Archbold said, “The idea that there is some middle way between God’s law and God’s mercy is merely a sop to the weak minded and the weak willed to make them feel better about accepting a little heresy.”

But I think so little about how to think is taught to most people, and so much has the corruption of the intellectual life seeped into the public discourse, that we might be being a little unfair. People are not taught that a thing and its opposite cannot both be true. They are not taught that there can’t be anything between two opposed propositions. And they are not taught that a thing is what it is and is not another thing.

But it’s not really that hard to understand the foundations of rational thought, and from there, to extrapolate a method (logic) of figuring out what is and is not true, once they’re adequately explained. These laws are so basic that they are like the understructure of a house, and if you try to ignore them, it’s like trying to build a house in mid-air. This is why we call it “metaphysics,” because it’s the stuff that underlies our understanding, it’s the conceptual framework we use to hang thought on.

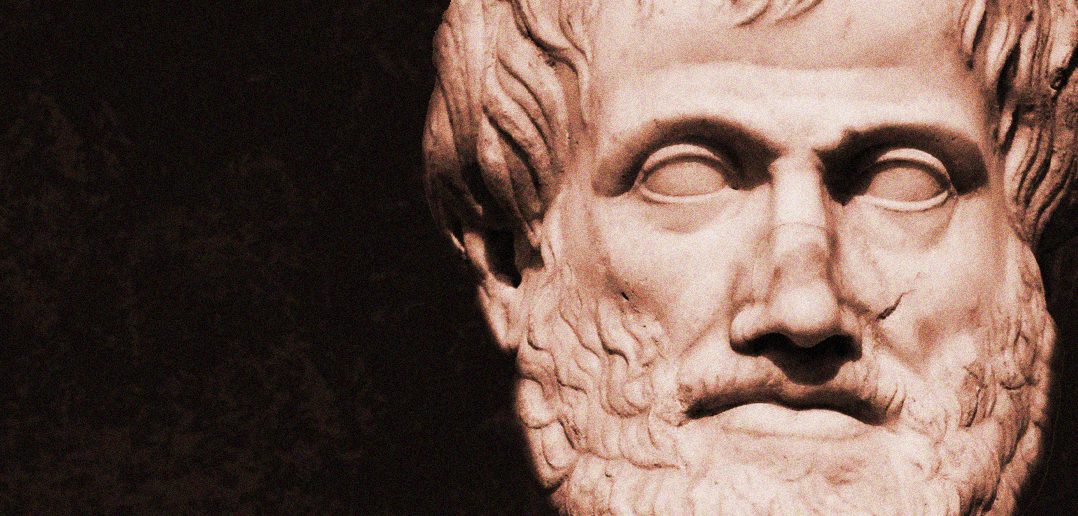

Aristotle codified these laws, but they are named and discussed in the ancient literature all the way back as far as anyone has recorded. Wikipedia (with a certain amount of deafness to the irony) describes them thus: “The laws of thought are fundamental axiomatic rules upon which rational discourse itself is often considered to be based.”

Without these three basic “axiomatic rules,” it is impossible to conduct any kind of human intellectual work. They are to the ability to reason, (which means to figure out what is and is not true) as basic arithmetic is to particle physics. Indeed, we would never have figured out anything about basic arithmetic if we didn’t start with these fundamental laws, even if only unconsciously.

They are closely related and sound quite a bit like each other, and when you say them out loud, you wonder why anyone would have bothered to say such obvious things: The Law of Identity, the Law of Non-contradiction and the Law of the Excluded Middle.

I’ve written a lot in the last 15 years about the Law of Non-Contradiction, which gets expressed in a lot of different ways, but simply says that “a thing and its opposite cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time.” I can’t be both in the room and not in the room at the same time.

From this we get notion that some things can be “mutually exclusive,” or “logically incoherent,” which can be applied to a lot of things in life. And we can say from this idea that some statements are meaningless or nonsensical because they are self-contradictory: “My brother is an only child.” You can’t be a polytheistic Muslim, for instance, since the one basic tenet of Islam is that there is only one god.

(Interestingly, the LP of Non-C is also where we get irony. If irony is simply a literary or rhetorical device in which a statement is made that is clearly opposed to the facts – “Oh, what a LOVely day!” when it is pouring with rain – it would be impossible if we didn’t have the basic concept of identity and opposition, that there can be a thing that is utterly and completely, perfectly and irreversibly not another thing. Which, I think, is why the people we often call “liberals” are often profoundly “irony-impaired”. Liberalism can only be achieved in the human mind by a corrosion of intellectual powers brought about by the attempt to deny or ignore one or more of the Three Laws of Rational Thought.)

When we say that something is self-contradictory or logically contradictory or logically incoherent, we are really saying that the given statement is meaningless. As Douglas Adams once facetiously put it, it “disappears in a puff of logic”.

So important is it, and so utterly impossible would it be to proceed without it in any intellectual endeavour, even one as simple as a conversation about the weather, that the Persian philosopher, Avicenna once famously wrote, “Anyone who denies the law of non-contradiction should be beaten and burned until he admits that to be beaten is not the same as not to be beaten, and to be burned is not the same as not to be burned.” And he recommended this ferocious treatment because in a very real sense, a person who tries to deny the LP of Non-C cannot be spoken to reasonably at all.

One of the things that has made me very, very worried about the world is the fact that this basic law of rationality is now routinely denied (yes, that’s ironic… I see you’re catching on). I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had people say to me, with perfectly straight faces and utter sincerity, “But there’s no such thing as objective truth…” The very, very popular notion that “my reality is different from your reality” or “you make your own reality” or “everyone decides for himself what is and is not true” are all implicit denials of this first, fundamental law of rational thought, without which we have no tools to even describe reality. These are all statements that are completely devoid of meaning at a most basic logical level. But they are parroted again and again by nearly everyone you meet and almost never refuted.

A lot of people out there in the world couldn’t understand why so many Traditionalists were so upset when Pope Francis said in that La Repubblica interview, “Each of us has a vision of good and of evil. We have to encourage people to move towards what they think is Good.” (In the end, it turned out that the interviewer may very well have simply made the comment up out of his own head, so… whatever. But even if Pope Francis didn’t say it and Scalfari made it up, it shows how far down we have sunk that this “leading Italian intellectual” thought it was something profound and meaningful enough for a pope to say. This is the sort of thing that “leading intellectuals” think makes sense.)

I could go on.

But the next thing that we have not talked about much is these other two: the Law of Identity and the Law of the Excluded Middle.

Again, simply, they are, respectively, “A thing is that thing and not some other thing,” and “Between two opposed things, there cannot be a third, middle thing.”

The Law of Identity is sometimes put like this: “For any proposition A: A = A” or like this, “each thing is the same with itself and different from another” – but you get the idea. Now, to get an idea of how fundamental this is, try for a moment to imagine a universe where this idea is not. Imagine this proposition: “A thing is the same with another thing and not with itself.”

Read it again a few times until it sinks in. It’s not possible. It is “anti-Real”.

And you can start to see how these metaphysical concepts are the notions that underlie all our other ideas about the nature of reality. Euclid used them implicitly when he invented geometry, which is really just the first stages of mapping reality in mathematical terms. (OK, yes, I know Euclid didn’t “invent” geometry… but you get my drift.) In fact, it could be argued that the Law of Identity is that notion from which all mathematics starts.

Euclid said in Book 1 that the very first of his “Common Notions, sometimes called axioms,” that are the first starting point of all the rest of his mathematics, is “1. Things which equal the same thing also equal one another,” … and he was off!

And the Law of the Excluded Middle that Aristotle described as, “there cannot be an intermediate between contradictories.” Think about it. What is there “between” being in the room and not in the room?

Aristotle wrote: “there cannot be an intermediate between contradictories…This is clear, in the first place, if we define what the true and the false are. To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true; so that he who says of anything that it is, or that it is not, will say either what is true or what is false.”

Reminds you of anything? “Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil; Who substitute darkness for light and light for darkness; Who substitute bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter! Woe to those who are wise in their own eyes And clever in their own sight!” (Isaiah 5:20-21)

And “I call heaven and earth to witness against you today, that I have set before you life and death, the blessing and the curse. So choose life in order that you may live, you and your descendants, by loving the LORD your God, by obeying His voice, and by holding fast to Him…” (Deuteronomy 30:19-20)

Note that there isn’t anything in there that says, “Unless you find it very difficult to decide, in which case, you can have a third thing that is comfortable and non-threatening.”

Now, I realise that even with this little brief introduction it is clear that we could go on all day. And all night. And for the next century, and people have. But this is where you start, and without this, no start can be made. And attempting to make a start by starting without any of this stuff, you go nowhere.

So, when a bishop or a pope says to you, “There should be a third way of ‘mercy’ between yes you can and no you can’t,” tell them Aristotle disagrees.

Originally published on October 20, 2014.