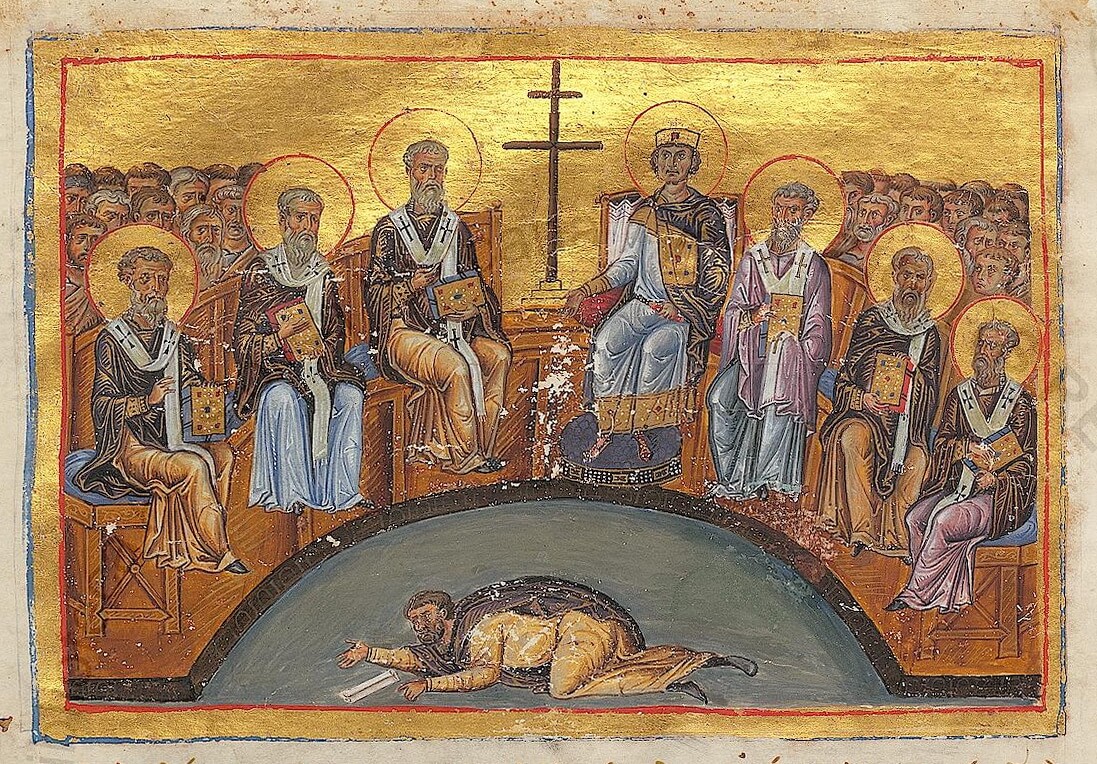

Illuminated manuscript (above): depiction of the Second Council of Nicaea from the Menologion of Basil II

His teaching thus finds its place in the tradition of the universal Church, whose sacramental doctrine foresees that material elements taken from nature can become vehicles of grace by virtue of the invocation (epiclesis) of the Holy Spirit, accompanied by the confession of the true faith (Pope Benedict XVI, General Audience, 6 May, 2009).

St. John Damascene

Born: 676

Died: approx. 749

Proclaimed a Doctor of the Church: 1890 by Pope Leo XIII

Feast Day (pre-1962 calendar): March 27th

More so than any of the ancient Doctors of the Church I have written about, there is so little known about St. John Damascene that studying biographical elements of his life is a quick and relatively fruitless task. He was born in Damascus under total Muhammadan control, though he was raised in a Christian family. Upon his father’s death, he took over his position as a financial official in the Islamic government (at this time Christians and Jews were employed in the bureaucracy by the Muhammadans after their invasion of the Roman and Persian empires). He did not last long there, however, before he left and joined a monastery outside of Jerusalem. Interestingly enough, his life under Muhammadan rule is what allowed him to write freely against the heresy of certain Christian rulers without fear of penalty.

St. John is not known for his own theological genius, but for his magnificent work of cataloging and compiling the teachings and writings of the great Greek fathers that came before him – in this sense he is a forerunner to western Scholasticism and the great Peter Lombard and his book the “Sentences.” (Some Eastern Orthodox ignorantly disdain western Scholasticism, but they fail to realize just how “scholastic” was their own great saint and our doctor of the Church!). He is venerated in both the Catholic and Orthodox faiths and was a strong defender of Mary’s title “Theotokos.”

Because so little of his biographical information is verifiable, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Leo XIII due almost entirely to his writings, some of which will be addressed here.

In the early part of the 8th century an Eastern Roman emperor named Leo the Isaurian issued a decree forbidding the traditional veneration of holy images. This became known as the Iconoclast heresy and the debate would rage for over one hundred years, producing many martyrs through the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 (the Seventh Ecumenical Council), at which John’s writings were leaned upon heavily, and finally the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” in 843. We note here in passing that this Ecumenical Council issued this decree which concerned not even the liturgy itself, but something even less “authoritative,” the devotional practice of icon veneration:

If anyone rejects/despises (athetei) any written or unwritten ecclesiastical tradition, let him be anathema.

This anathema shows the Catholic attitude toward all Tradition – the deposit of faith, the sacred liturgy, the monuments of our forefathers and even, in this case, the pious devotions of the faithful. The confusion about this devotion to icons was that venerating or praying before an image might be a violation of the first commandment, something Protestants still assert to this day. Perhaps St. John’s greatest contribution to orthodoxy is his defense of the veneration of images and the distinction between veneration and true worship, which is reserved for God alone.

His work is generally divided into a few parts and much of it is a transcription with minor updates to the works of the Greek Fathers, but On Holy Images is a writing entirely unique to St. John. In this work he defines what an image is, why an image might be made, and what he categorizes as the six kinds of images:[1]

- The natural image, which is a way to explain how God the Son is a “natural and unchangeable image of the invisible God, the Father, showing the Father in Himself.”

- The “eternal and unchanging counsel” of God. This is a way to describe the image in God’s mind of what is to be.

- The image of God himself, which is man. We are an imitation or image of the Trinity. As St. John writes: “As Mind [the Father], the Word [the Son], and spirit [the Holy Spirit], are one God, so mind and word and spirit are one man.”

- “Prefigurations and prototypes set forth by Scripture of invisible and immaterial things in bodily form.” St. John explains that everything in nature is some sort of image or type of God’s divine attributes. He says that “from the creation of the world the invisible things of God are made clear by the visible creation.”

- The fifth image is similar to the fourth, but is a more specific prefiguration rather than general. St. John gives the example of the poisonous snakes being raised up on stakes being a prefigurement of Christ healing all from the cross or God creating the sea as a type of baptism.

- The image to remember past events, “for the honor and glory and abiding memory of the most virtuous, or for the shame and terror of the wicked, for the benefit of succeeding generations who see it, so that we may avoid evil and do good.” This kind is subdivided into two further types:

- Written word

- Visible object

This seems like a lot of intellectual work to understand a pretty simple concept, but keep in mind that St. John was writing to persuade people against the Iconoclasts, so he had to start from the beginning and work systematically through every type of image and, in turn, every type of worship, adoration, or veneration in order to distinguish what these images and icons are and how they are being revered.

He describes seven types of worship and says that it is clear in Sacred Scripture that God’s people rightly venerated such objects or images as the Scriptures, chalices, altars, or Aaron’s staff. Early Christians, he says, rightly venerated the stable at Bethlehem or mount Golgotha.

After he lays out the types of images and types of worship with ample Scriptural references, he closes with a rather stunning and beautiful paragraph, part of which I have reproduced here:

You see what great strength and divine energy are given to those who venerate the images of the saints with faith and a pure conscience. Therefore, brothers, let us take our stand on the rock of the faith, and on the tradition of the Church, neither removing the boundaries laid down by our holy fathers of old (Prov. 22.28), nor listening to those who would introduce innovation and destroy the economy of the holy Catholic and Apostolic Church of God. If any man is to have his foolish way, in a short time the whole structure of the Church will be reduced to nothing. Brothers and beloved children of the Church, do not put your mother to shame, do not rend her to pieces. Receive her teaching through me. Listen to what God says of her: ‘You are all fair, O my love, and there is not a spot on you’ (Cant. 4.7). Let us worship and adore our God and Creator as alone worthy of worship by nature, and let us worship the holy Mother of God, not as God, but as God’s Mother according to the flesh. Let us worship the saints also, as the chosen friends of God, and as possessing access to Him… Thus, we hold images worthy, and it is not a worship of matter, but of those whom matter represents. The honor given to the image is referred to the original, as holy Basil rightly says.

St. John uses first principles, Scriptural references, and poetic persuasion to prove to the Iconoclasts what most Christians intuitively know: God has given us a tangible faith through the incarnation of His son, God made man. He physically entered our world and experienced it with His senses. The Christian Tradition has always used holy objects to reflect a deeper meaning, much like Christ’s parables. Our entire experience of God through sanctifying grace culminates in physically receiving Him into our bodies by eating His flesh and drinking His blood. One can easily see how a rejection of the reality of the Sacraments will in turn lead to a rejection of holy imagery and any other physical, visible, tangible devotional object. Though there is one question that still nags me: Protestant friends, do you set up a nativity scene at Christmas?

I was thrilled to read St. John’s work because one of my favorite books, from which my wife and I got the idea to build our Catholic company with Kendra Tierney, is Mike Aquilina’s A History of the Church in 100 Objects. Aquilina walks the reader through all of Christian history, associating each time period or major event with a specific object of importance to that time and story. It is fascinating to see how people have always used what we would now call sacramentals to help them increase their faith and practice their worship of God, and St. John Damascene is perhaps the greatest defender of this tradition.

We have always experienced God in a physical way, from the burning bush to the quiet wind in the cave to the Incarnation. God becoming human is the theological basis for venerating holy images and objects, as St. John proves, and any rejection of the latter will start to muddy the waters of your belief in the former.

Lamentably, the west suffered a similar Iconoclasm first with the Protestant revolt, when the heretics smashed beautiful and timeless images and statues of Our Blessed Mother and destroyed the holy relics of saints. But a new and more subtle Iconoclasm arose and infected the liturgical movement, diverting its good origins from 19th century France into excesses in rationalism and antiquarianism.[2] The liturgical reform under Pius XII specifically attacked the devotional customs of the faithful and their use of sacramentals.[3] And as we know, the construction of the Novus Ordo Missae and its imposition on all the faithful of the Roman Rite followed the same principles.[4] All of these efforts worked against the aforementioned anathema from the Seventh Ecumenical Council, brought about in part by St. John’s great work against the heretics.

But in our own day, the world witnessed one of the most heinous examples of muddying the water on this concept when, in 2019, Pope Francis allowed the worship (or least veneration) of a South American idol in the Vatican. If only the highest prelates in our Church were more familiar with the writings of this great doctor, perhaps such a travesty could have been avoided, or at least decried en masse after the fact.

It takes incredible (read: saintly) patience, clarity, and precision to articulate the Catholic position on the veneration of sacred images without dipping your toes into the opposite ends of the spectrum: on the one side, the Iconoclast heresy and on the other, idol worship. We need this kind of clarity as badly in the 2020s as we did in the 8th century. To that end, may we all implore the intercession of St. John; read his works, most especially On Holy Images; and be a witness to our Protestant friends and family, as well as to certain prelates of the Church in our veneration of sacred images.

St. John Damascene, pray for us!

[1] St. John Damascene, On Holy Images, trans. by Mary H. Allies (London, Thomas Baker, 1898), pp. 10-17.

[2] On this, see Rev. Fr. Didier Bonneterre, The Liturgical Movement – Guéranger to Beauduin to Bugnini: Roots, Radicals, Results (Angelus Press, 2002).

[3] On this see the Una Voce studies on the Latin Mass, edited by OnePeterFive contributing editor Joseph Shaw, The Case for Liturgical Restoration (Angelico Press, 2019), 121-128, 129-136. These sections are also available online here and here.

[4] On this, we refer the reader to the work of OnePeterFive contributing editor, Peter A. Kwasniewski.