The traditional Catholic lectionary — dating back to the first millennium of Christianity and, since the Middle Ages, included in the contents of the altar missal itself — includes far fewer readings than the revised (postconciliar) lectionary used for the Novus Ordo Mass. However, this is not a strike against the former, since the lectionary, prior to the mid-twentieth century, had never been conceived in any traditional Christian liturgy as a sightseeing tour of the Bible, designed by Germanic docents and led week to week, more or less competently, by Father Jimmy. Rather, the Epistle and Gospel for each Sunday, feast day, or Lenten weekday was chosen with a view to its immediate moral lesson for the congregation or for its intimate relationship with the Most Holy Eucharist and the other sacraments of the Church. The Scripture was selected for its obvious relevance to the daily lives of Catholics or for its power to lead the mind deeper into the mysteries enacted on the altar — themselves a reflection of the perfect worship of the Church triumphant in the heavenly Jerusalem.

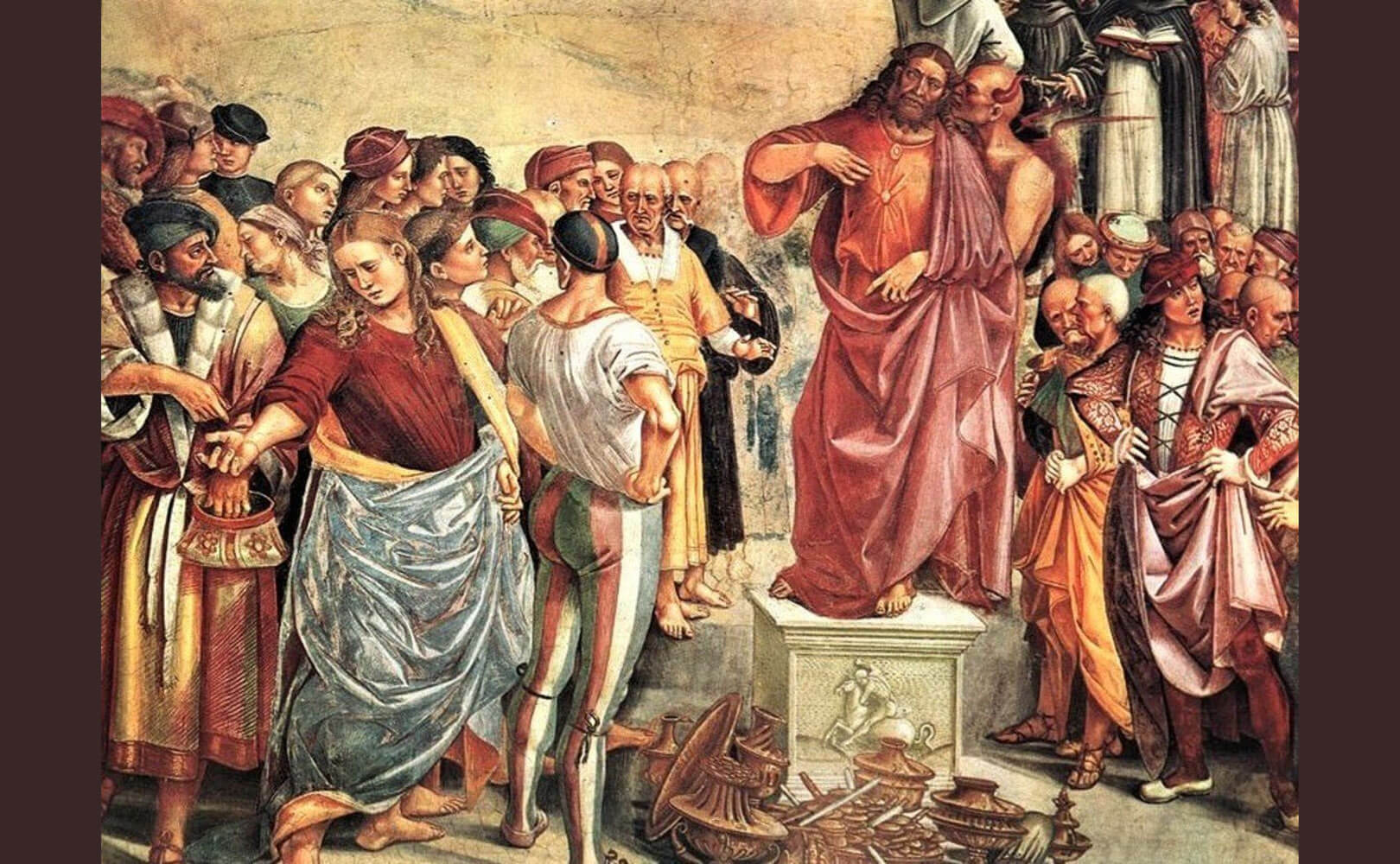

Traditionally, at least since the invention of printing, the Catholic Church had emphasized other ways to become familiar with Scripture, two of which were the ample readings included in the Divine Office (Matins in particular) and the practice of lectio divina or personal, prayerful study of Scripture. That these ways were successful in promoting biblical literacy can be seen in countless homilies and commentaries from the patristic period down into modern times, permeated with a sophisticated grasp of the full range of the Bible’s teaching, and in the clever use made of a wide range of biblical themes and symbols in stained glass windows and other church decorations, a veritable biblia pauperum or “Bible of the poor” by which laity were educated about salvation history, its great figures, and their connection with Christ, the axis on which all of human history, and indeed the cosmos in its entirety, turns.

In other words, the readings of the old lectionary were chosen for their practical value, their liturgical fittingness, and their memorability through repetition so that they might sink deep roots into the soul [1] — not on the abstract principle that we should “read as much of the Bible as possible” at Mass. This latter principle is, in any case, impossible to actualize, since the Bible is still much too large to be contained in a lectionary without remainder, even allowing for cycles of two or three years.

But the plot thickens when we realize that the new lectionary not only greatly multiplied the number of readings in toto, but also carefully left out passages of Scripture that were deemed too “difficult” for Modern Man — and, indeed, removed pieces of Scripture that had been read at Mass for well over 1,000 years. The same expurgation was visited on the Psalms in the Liturgy of the Hours. It is really extraordinary to see how craftily the scissors and paste were plied, as readings often skip a key verse or series of verses that potently convey the realism and challenge of the Word of God, confronting us fallen human beings with a call to conversion and vigilance [2].

All of this was on my mind recently when a friend asked me a question about a reading he had heard at the Novus Ordo this past Sunday, taken from St. Paul’s Second Epistle to the Thessalonians. I decided to look into how the new lectionary makes use of this epistle.

As we would expect, more of it is quantitatively read in the Novus Ordo lectionary: it comes up six times, thrice on weekdays and thrice on Sundays. But the most spine-tingling passage of the letter, and the one that, frankly, is on the minds and lips of many people today as we look at an accelerating decomposition of Catholicism at the Vatican, is precisely the one passage that is included in the Tridentine Missal and excluded in the revised lectionary!

Last weekend on the new calendar fell the Thirty-First Sunday in Ordinary Time (Year C), for which the second reading is 2 Thess 1:11–2:2. This coming weekend, the Thirty-Second Sunday in Ordinary Time, “continues” with 2 Thess 2:16–3:5. Anyone who looks at the fine print will naturally wonder: What happens in verses 3 to 15, which are skipped over?

3 Let no man deceive you in any way; for that day will not come, unless the rebellion comes first, and the man of lawlessness [or man of sin] is revealed, the son of perdition,

4 who opposes and exalts himself against everything that is called God or that is worshipped, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God.

5 Do you not remember that when I was still with you I told you this?

6 And you know what is restraining him now, so that he may be revealed in his time.

7 For the mystery of lawlessness [or iniquity] is already at work; only he who now restrains it will do so until he is out of the way.

8 And then the lawless [or wicked] one will be revealed, and the Lord Jesus will slay him with the breath of his mouth and destroy him by his appearing and his coming.

9 The coming of the lawless one by the activity of Satan will be with all power and with pretended signs and wonders,

10 and with all wicked deception for those who are to perish, because they refused to love the truth that they might be saved.

11 Therefore God sends upon them a strong delusion, to make them believe what is false,

12 so that all may be condemned who did not believe the truth but had pleasure in unrighteousness [or consented to iniquity].

13 But we are bound to give thanks to God always for you, brethren beloved by the Lord, because God chose you from the beginning to be saved, through sanctification by the Spirit and faith in the truth.

14 To this he called you through our gospel, so that you may obtain the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ.

15 So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter. (2 Thess 2:3–15)

Elsewhere in the revised lectionary (Tuesday of the Twenty-First Week in Year B, to be exact), some of the foregoing is read: verses 1–3a appear (stopping at “in any way”), then jumping ahead to verse 14, skipping the entire discussion of the Antichrist and God’s punishment of those who imitate or follow him.

In this portion of the Word of God, St. Paul warns the Thessalonians to be on guard and not to be deceived by the Antichrist, who sets himself up against the Faith and against true worship of the one and only God (one cannot help but think of Abu Dhabi and the Amazon Synod). The apostle notes that God Himself will restrain the coming of this evil for a time, but not forever, and that those who refuse to love the truth (think of the error introduced into the Catechism) and who consent to iniquity (think of Amoris Laetitia) will be abandoned to delusion and deception, so that they will not be saved. It is sanctification by the Spirit and faith in the truth of the Gospel that lead to salvation — and this Gospel is handed down in traditions that we receive as members of the Church, such as our traditional rites of worship. These rites permanently embody and rightly express the Gospel and the true Faith.

Thus, it is not surprising that a substantial portion of this omitted passage turns out to be the one reading from Second Thessalonians in the traditional Latin Mass (2 Thess. 2:1–8). Because there are no “Years A, B, C” and no “long or short versions” to be found in the ancient missal, the following passage is read every year on Ember Saturday of Advent:

1 Now concerning the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our assembling to meet him, we beg you, brethren,

2 not to be quickly shaken in mind or excited, either by spirit or by word, or by letter purporting to be from us, to the effect that the day of the Lord has come.

3 Let no man deceive you in any way; for that day will not come, unless the rebellion comes first, and the man of lawlessness [or man of sin] is revealed, the son of perdition,

4 who opposes and exalts himself against everything that is called God or that is worshipped, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God.

5 Do you not remember that when I was still with you I told you this?

6 And you know what is restraining him now, so that he may be revealed in his time.

7 For the mystery of lawlessness [or iniquity] is already at work; only he who now restrains it will do so until he is out of the way.

8 And then the lawless [or wicked] one will be revealed, and the Lord Jesus will slay him with the breath of his mouth and destroy him by his appearing and his coming.

As most Scripture scholars agree, although the Antichrist will be a definite figure and person, the “coming of the Antichrist” may also be understood more broadly as an ongoing and escalating resistance to Christ as history nears its end. Surely there is much in Second Thessalonians that resonates with believers today, as they see wickedness in high places; hitherto unimaginable deviations from the commandments of God; and attempts, both subtle and flagrant, to corrupt the sober apostolic faith and “deceive even the elect, if it were possible” (Mt. 24:24).

Oh, by the way, that verse — “For false Christs and false prophets will arise and show great signs and wonders, so as to lead astray, if possible, even the elect” — is read every year at the traditional Latin Mass on the Last Sunday after Pentecost but appears nowhere in the new lectionary.

[1] For a detailed exposition of the virtues of the old lectionary and the defects of the new, see my article “A Systematic Critique of the New Lectionary, On the Occasion of Its Fiftieth Anniversary.” Those who prefer audio may appreciate this radio interview on the subject.

[2] Those who wish to see in detail how the old and new lectionaries differ in their use of Scripture should pick up this handy reference book.